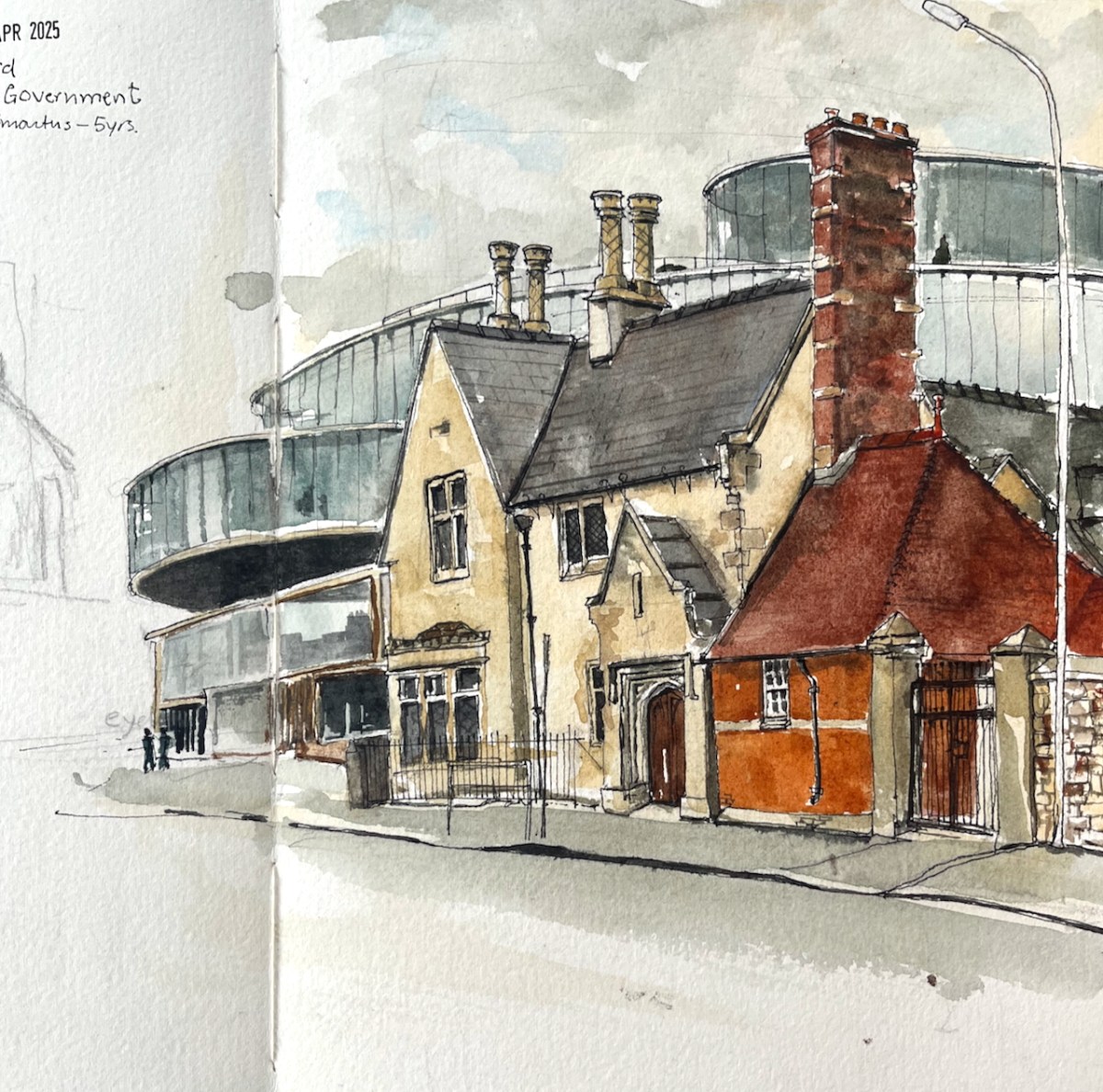

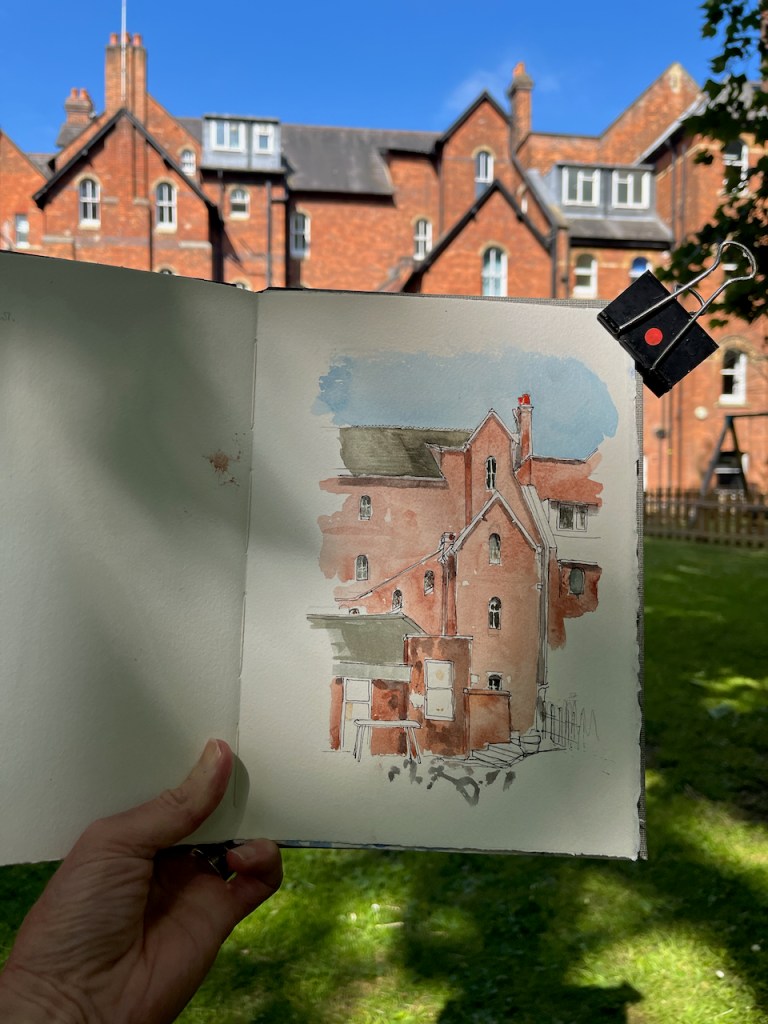

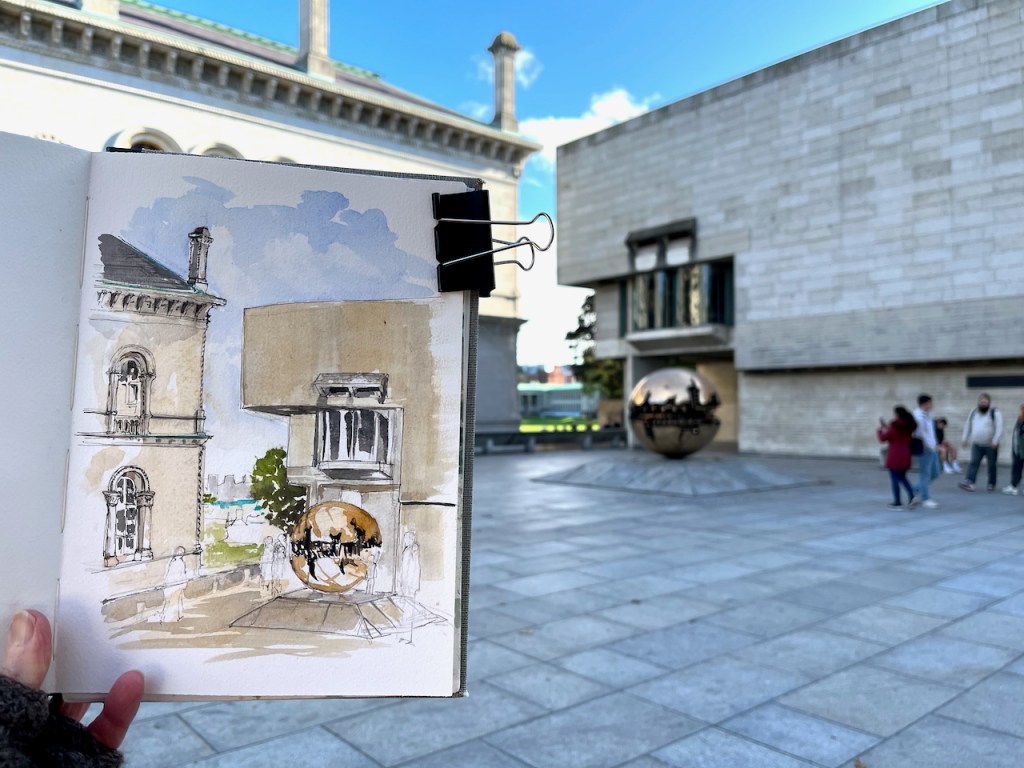

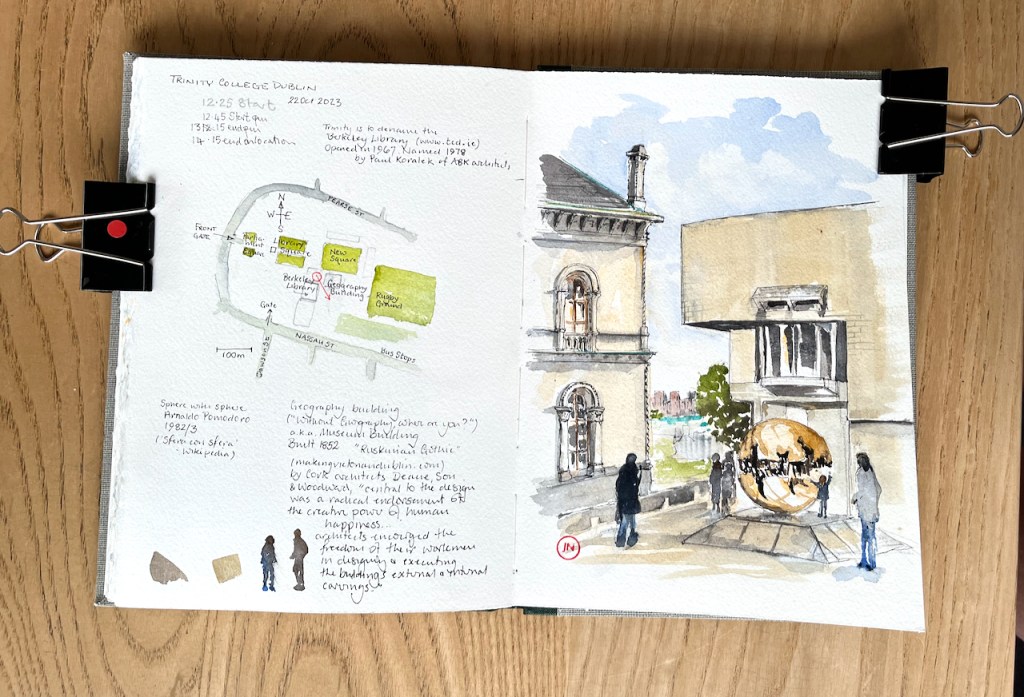

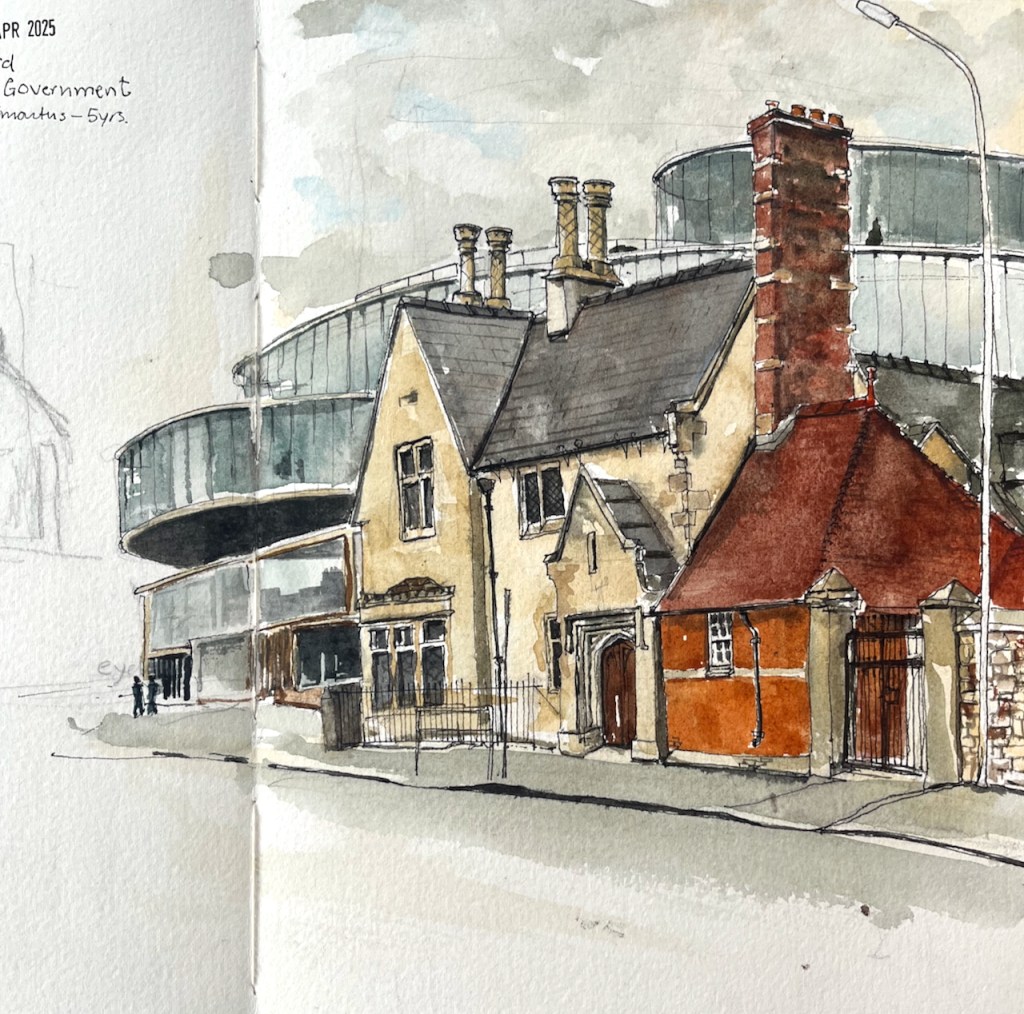

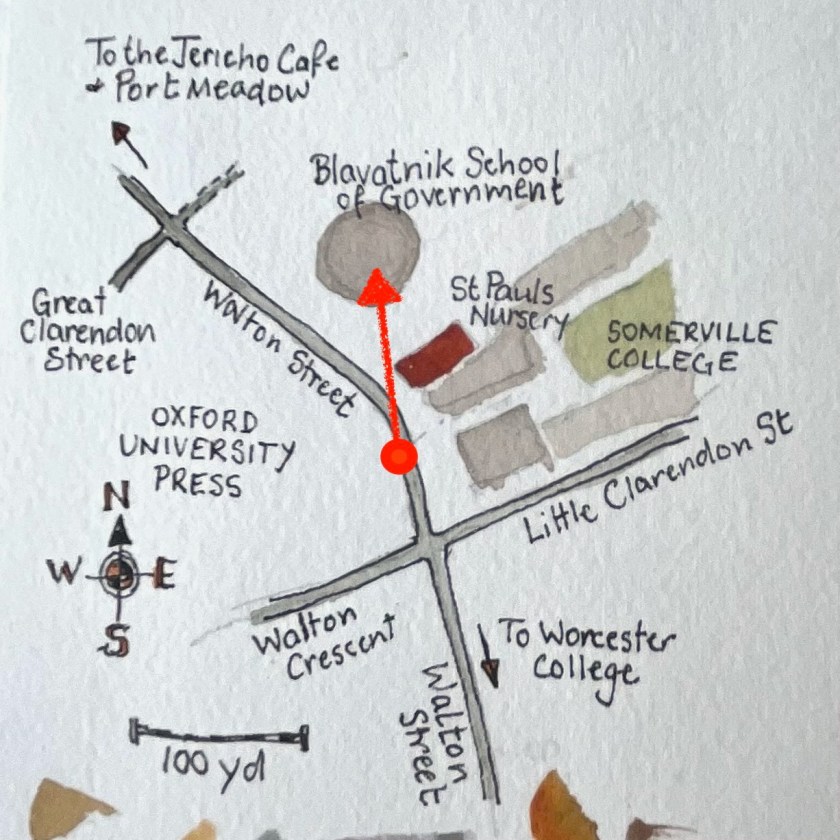

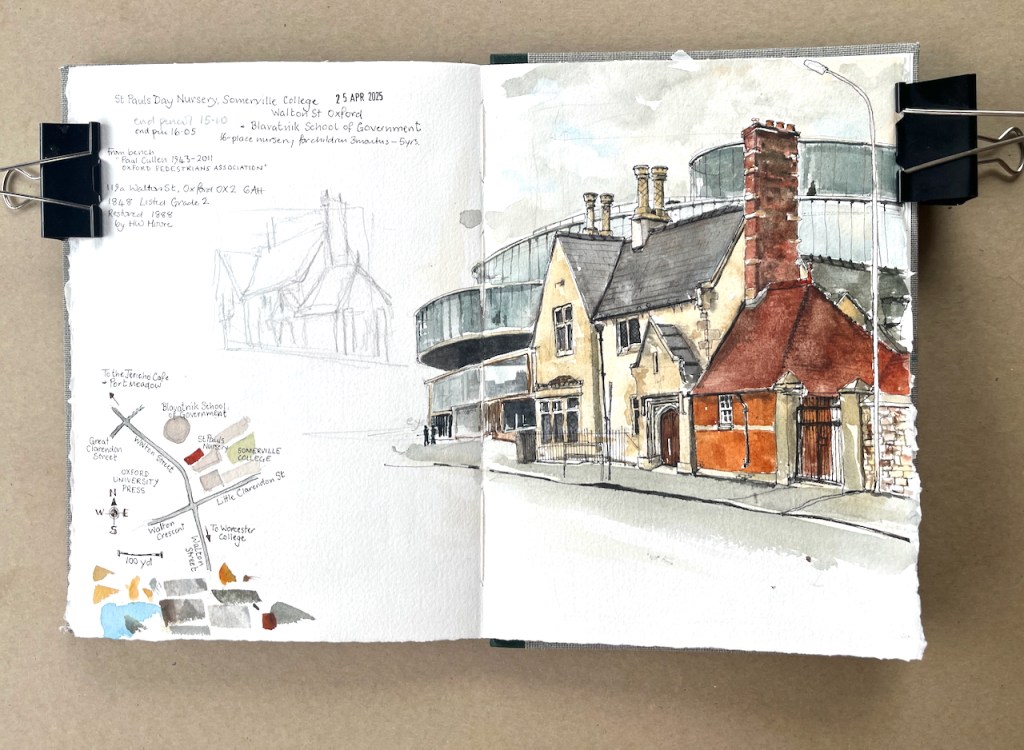

This 19th Century building on Walton Street is a nursery school. It contrasts with the huge sweeping curves of the Blavatnick School of Government behind.

The building now houses a co-ed nursery:

“St Paul’s Nursery is a 16-place day nursery that caters for children between the ages of 3 months and 5 years. The Nursery was established as a work place nursery for the staff of Somerville College, but now opens its doors to children whose parents work elsewhere.” [note 1]

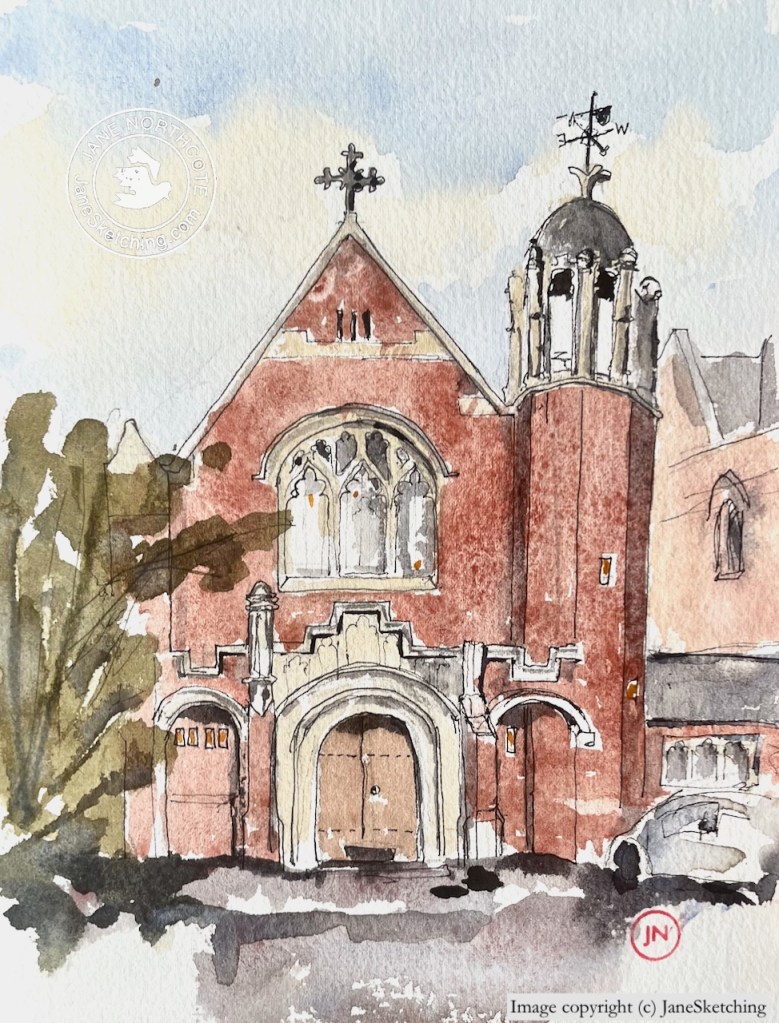

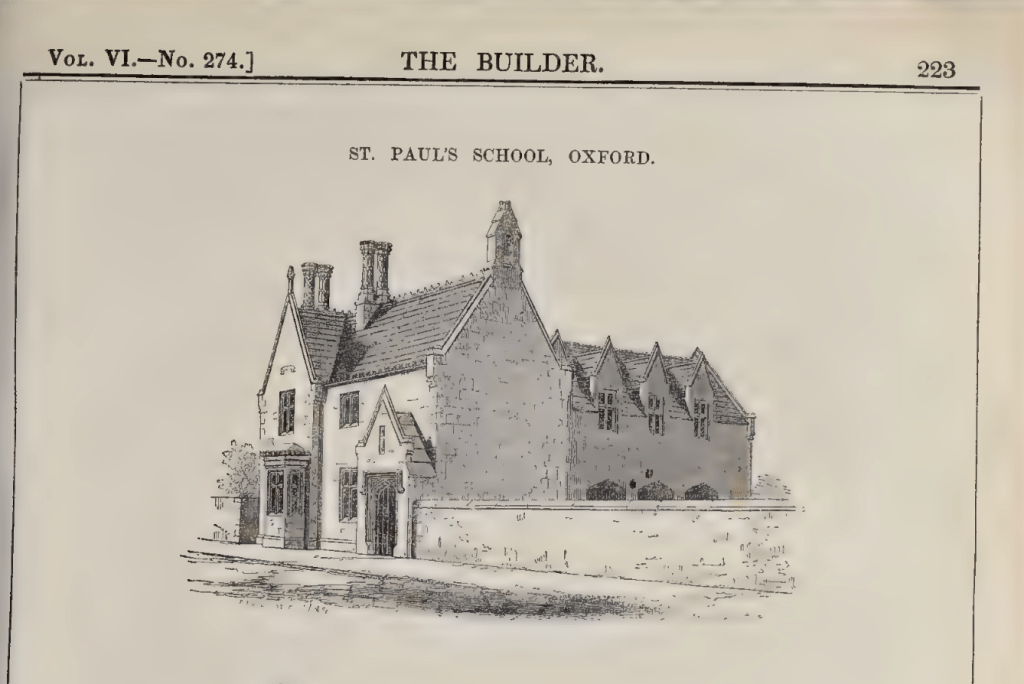

The original building of 1848 is described in “The Builder” magazine of that year. [note2]

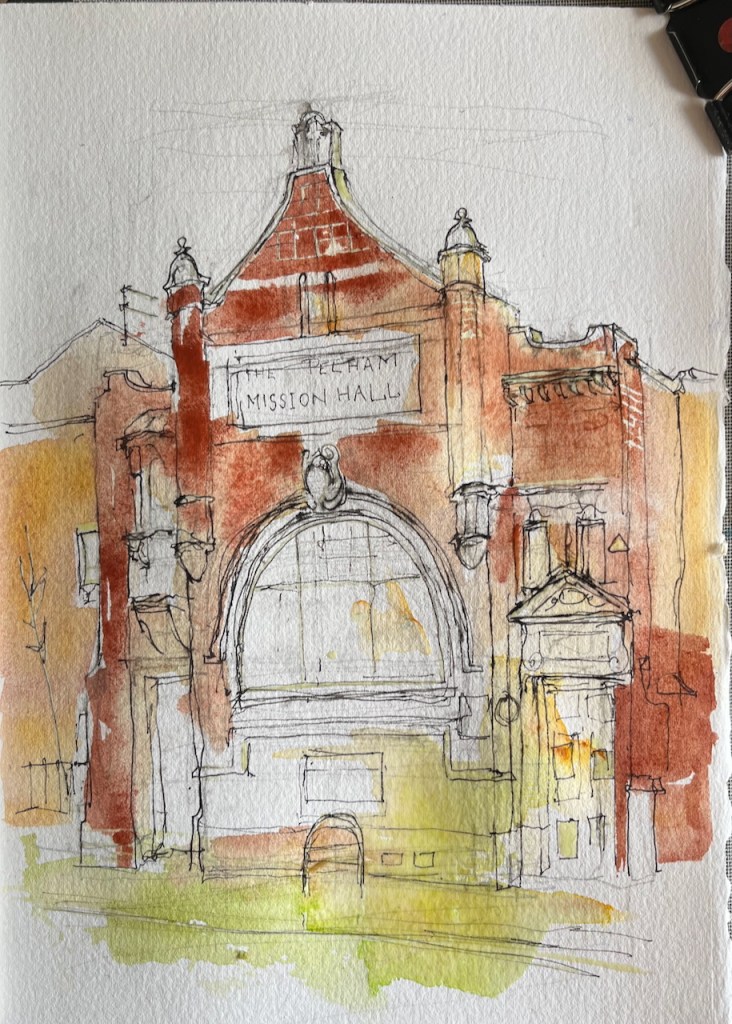

Here is what it looked like originally:

According to the (fascinating!) article in The Builder, the school was originally only for girls. Inside the building pictured above was a “dwelling house” for the mistress, a room for the vicar “to conduct his parochial business” , and a school room “55 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 18 feet between the apex and the floor”. Because there was no outdoor playground, the architect placed the school-room on the “second floor” and the lower room became the playground. I take it that by “second floor” the author meant what we now call “first floor”. The author of the article, who seems also to be the architect, describes with pride the construction of the roof:

“In the construction not a particle of wood has been used. The roofs are supported on terra-cotta ribs, with transverse sleepers of the same material, and the floors, arched on geometrical principles, are formed by tiles set in cement ; both are of undoubted strength and durability.” [from “The Builder” article, see note 2]

So the structural elements of the roof are terracotta? Really? If anyone has been inside this excellent building, can they tell me if this is still the case? Did the roof and the floors turn out to be durable, as the article says?

“St Paul’s Nursery” is now part of Somerville College. “St Paul’s Church” is the big building like a Greek temple which is on Walton Street on the other side of the Blavatnik building. It was out-of-use as a church by the early 1970s, and became a wine bar called “Freud”. It now looks sadly dilapidated. Some of its history is on this link.

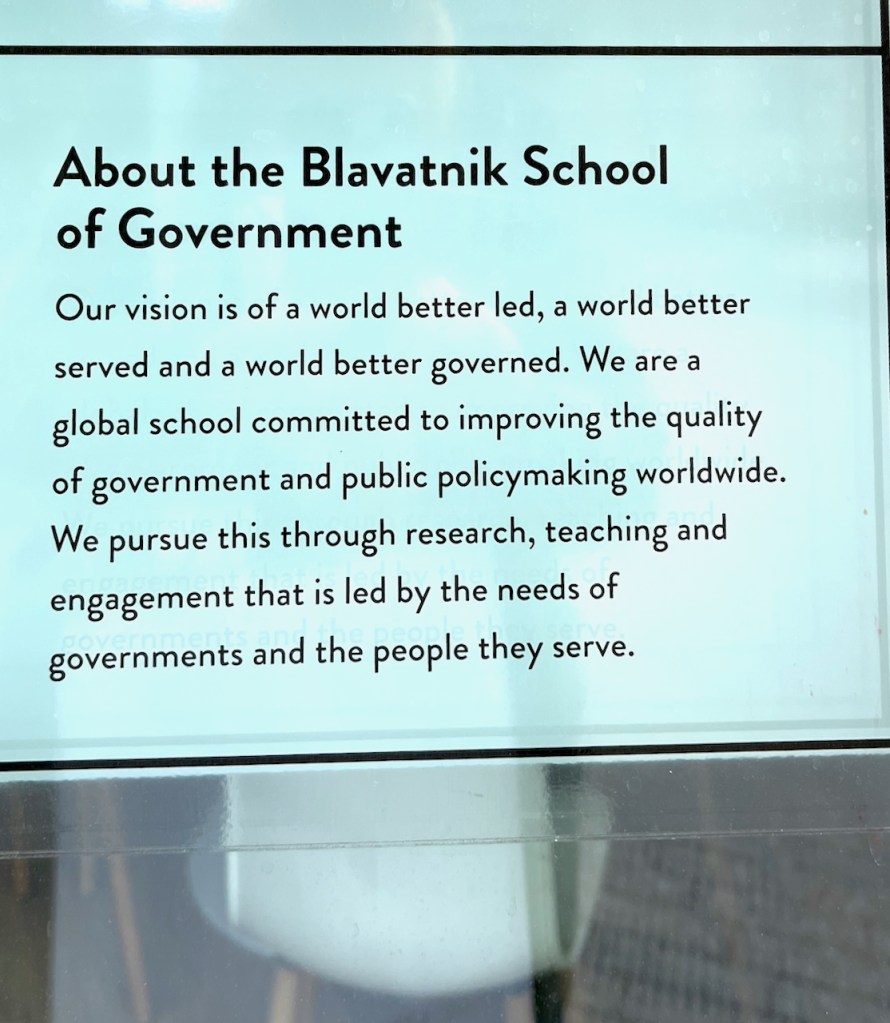

The Blavatnik School of Government started in 2012. It moved into the new building on Walton Street in 2016. The building is by Herzog and De Meuron. The architects’ drawings of it, and some internal and external photos are on this link.

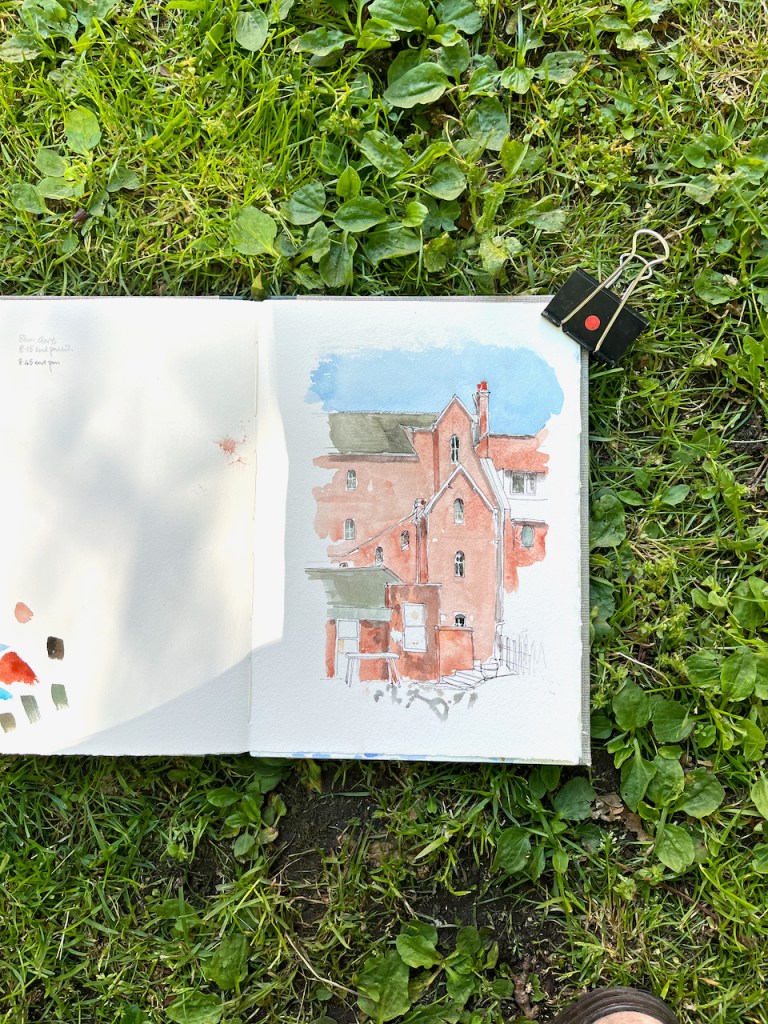

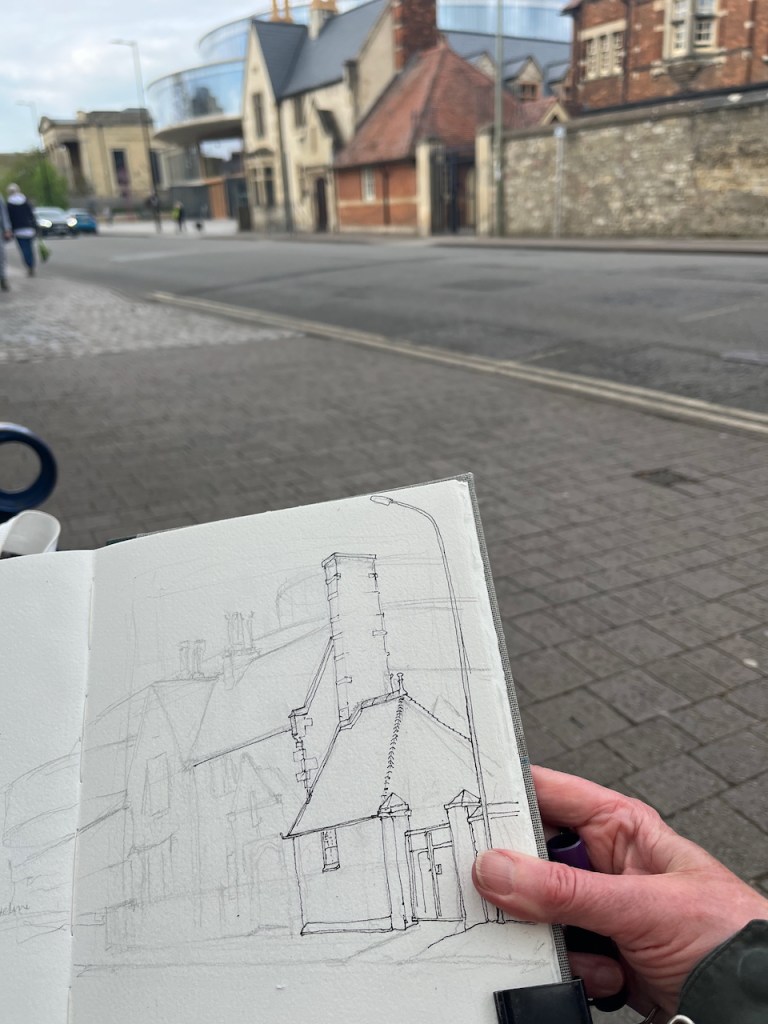

I made the sketch from a convenient bench outside the Oxford University Press. The bench was dedicated to

“Paul Cullen 1943-2011

Oxford Pedestrians Association”.

“Paul Cullen 1943-2011

Oxford Pedestrians Association”.

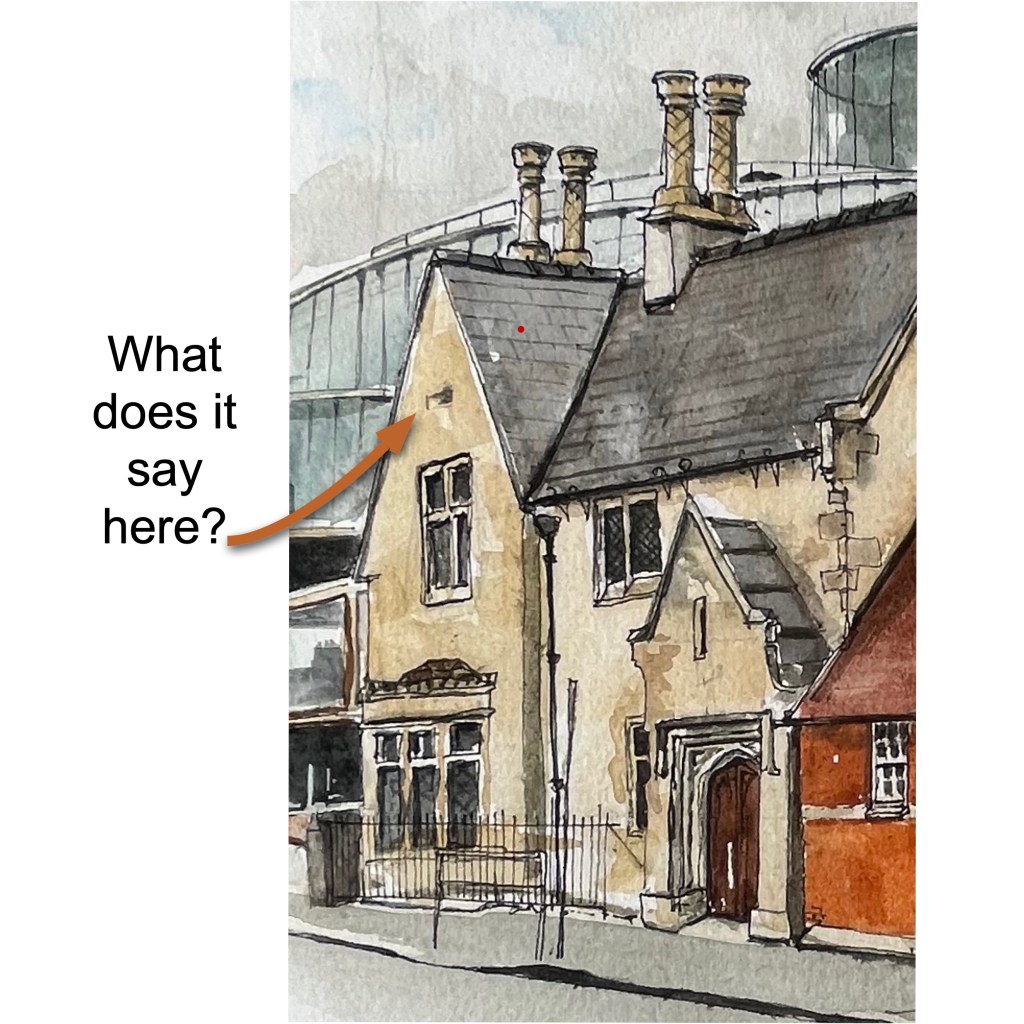

The inscription on the bench was easily read. But there was an inscription on the building I’d been drawing, and I couldn’t read that.

There is a stucco scroll with writing on the gable of the nursery building. Try as I might I could not read it.I assumed my ageing eyes were at fault. So I stopped two young people on the pavement and asked them if they could read it. They took my request seriously, and gave the task their full attention, which was kind of them. However they could not read it either. “Something Something CCC something something” was our joint conclusion. 1848 would be MDCCCXLVIII. Does it say that? If you are walking along Walton Street with a high-powered telescope, or if you have an old photo which shows the building in a less eroded state, then can you tell me what it says?

Note 1: Somerville College Website, Nursery Handbook, on this link:

https://www.some.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Nursery-Handbook-updated-June-2018.pdf

Note 2: “The Builder” magazine is online. You can find the 1848 volume at this link:

I have transcribed the letter relating to St Paul’s School: (2 pages pdf)

The letter is apparently written by the architect. They say, for example, “we have perhaps rather exceeded the bound of usual practice in ornamental detail” and refers to “our site”. But he or she does not sign their name, simply giving initials: “T.C.”. I have not been able to discover who “T.C.” is.