Here is the magnificent London Water and Steam Museum.

It’s definitely worth a visit if like me you are fascinated by steam engines. But there’s more. This museum is a whole education in the London drinking water and sewerage system: past and present.

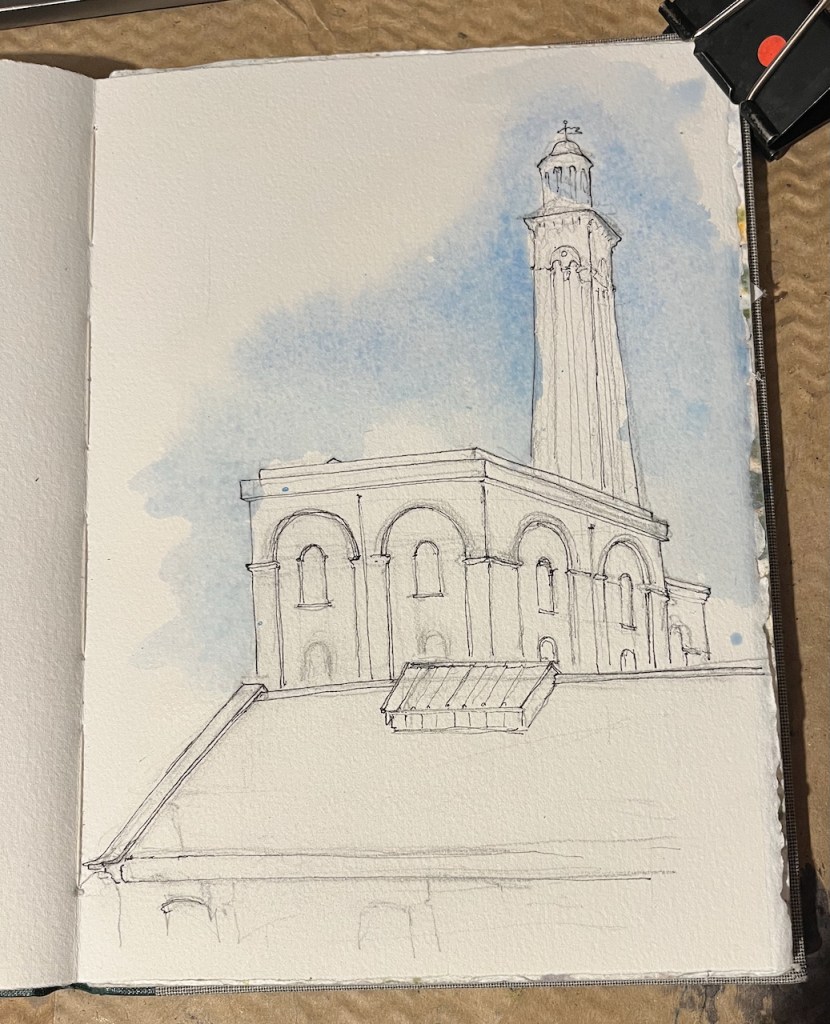

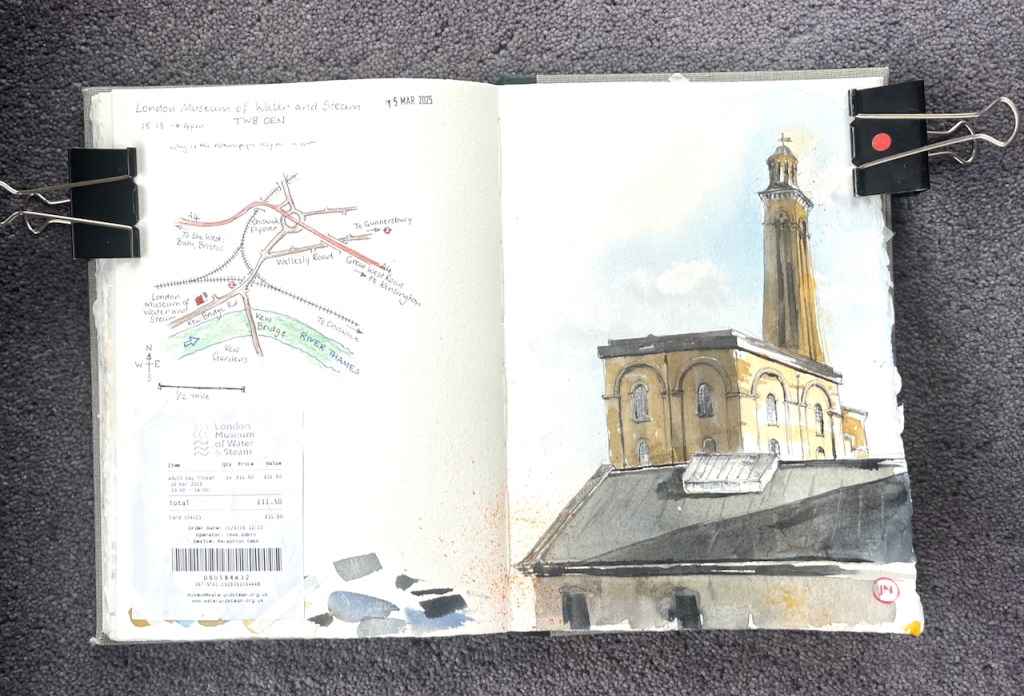

The building I’ve sketched houses the “100 inch pumping engine” and the “90 inch pumping engine”. These are steam pumps over a hundred years old. The inches refer to the diameter of the pump cylinder. Their job was to pump drinking water from the Thames to premises in London. The 90 inch engine started working in 1846 and the 100 inch started in 1871. They both retired in 1943, by which time the 90 inch had been going 97 years. The 100 inch gave a demonstration in 1958, which was the last time it pumped water. The 90 inch was restored to working order by enthusiasts in 1973, and now gives demonstrations in the museum. The 100 inch has yet to be restored.

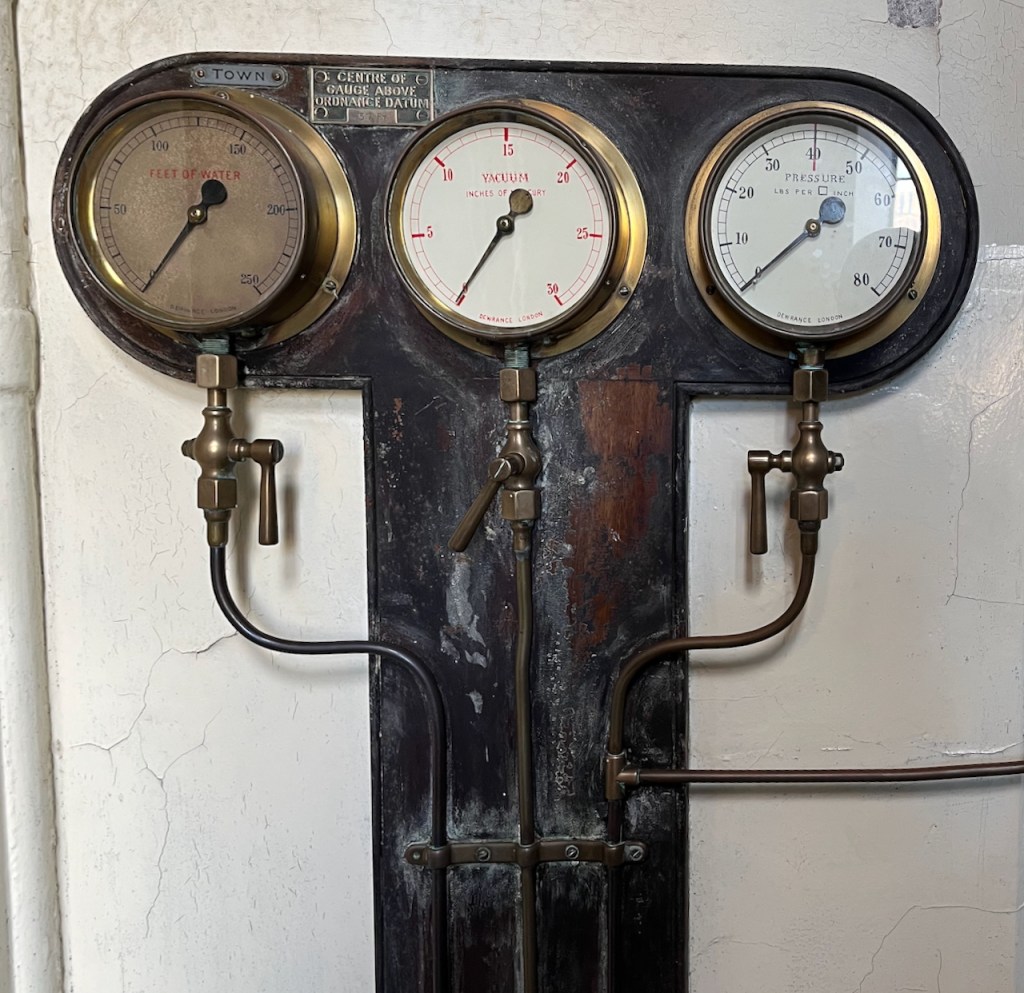

The tower in my sketch is not a chimney. It is a “standpipe tower”. It holds big vertical pipes and a reservoir to store water and regulate the pressure. The strokes from the steam engines created powerful surges of water. You don’t want those powerful surges going directly into the mains water supply, and as they might damage the pipes and surprise consumers. So the steam engines pumped the water up this tower instead. From there, the water flowed out to consumers smoothly.

Providing running water was a whole big problem in the Victorian era. The machines were gigantic so that they could generate sufficient water pressure to get the water up to the second floor of the new Victorian houses which had bathrooms upstairs. That’s not something we normally think about: but I can see it’s an issue.

Then there was the whole big issue of the purity of the water, and whether it was actually drinkable. There were a number of private water companies at the time, in competition with each other, and vying for business, making claims for their water quality, and returning dividends to their shareholders. This was the late 19th century – 100 or so years ago.

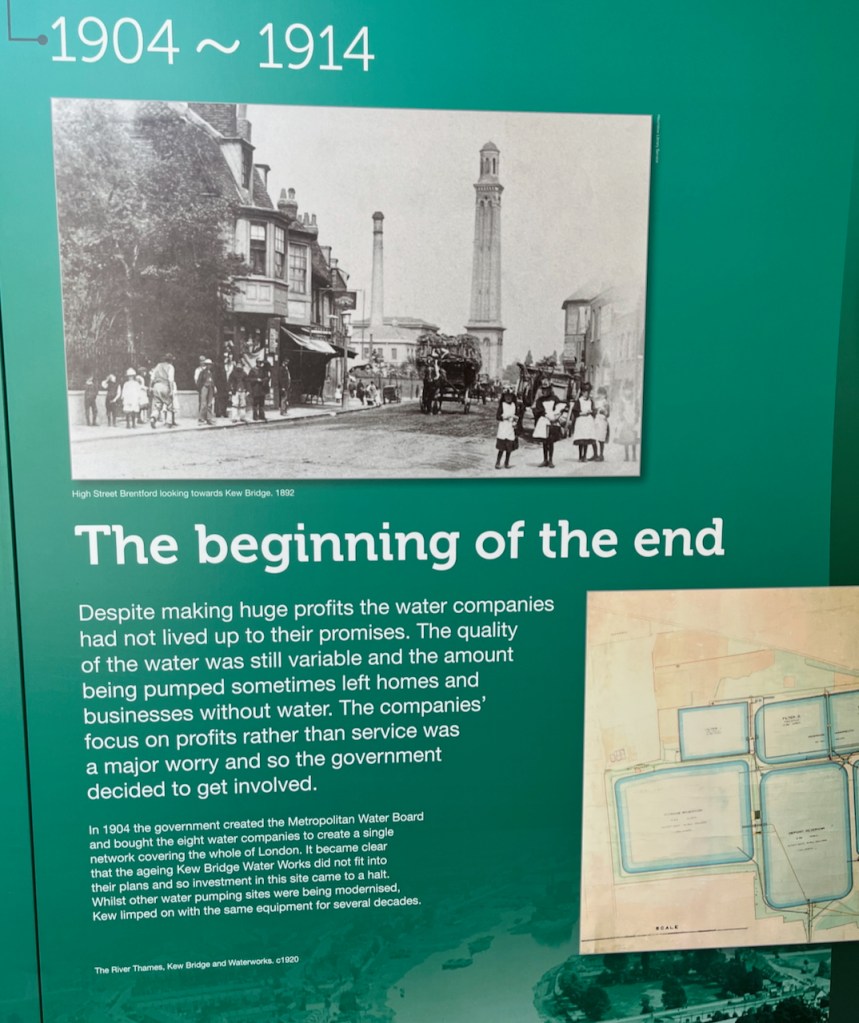

A display panel soberly tells us:

“Despite making huge profits the water companies had not lived up to their promises. The quality of the water was still variable and the amount being pumped sometimes left homes and businesses without water. The companies’ focus on profits rather than service was a major worry and so the government decided to get involved.

In 1904 the government created the Metropolitan Water Board and bought the eight water companies to create a single network covering the whole of London. …

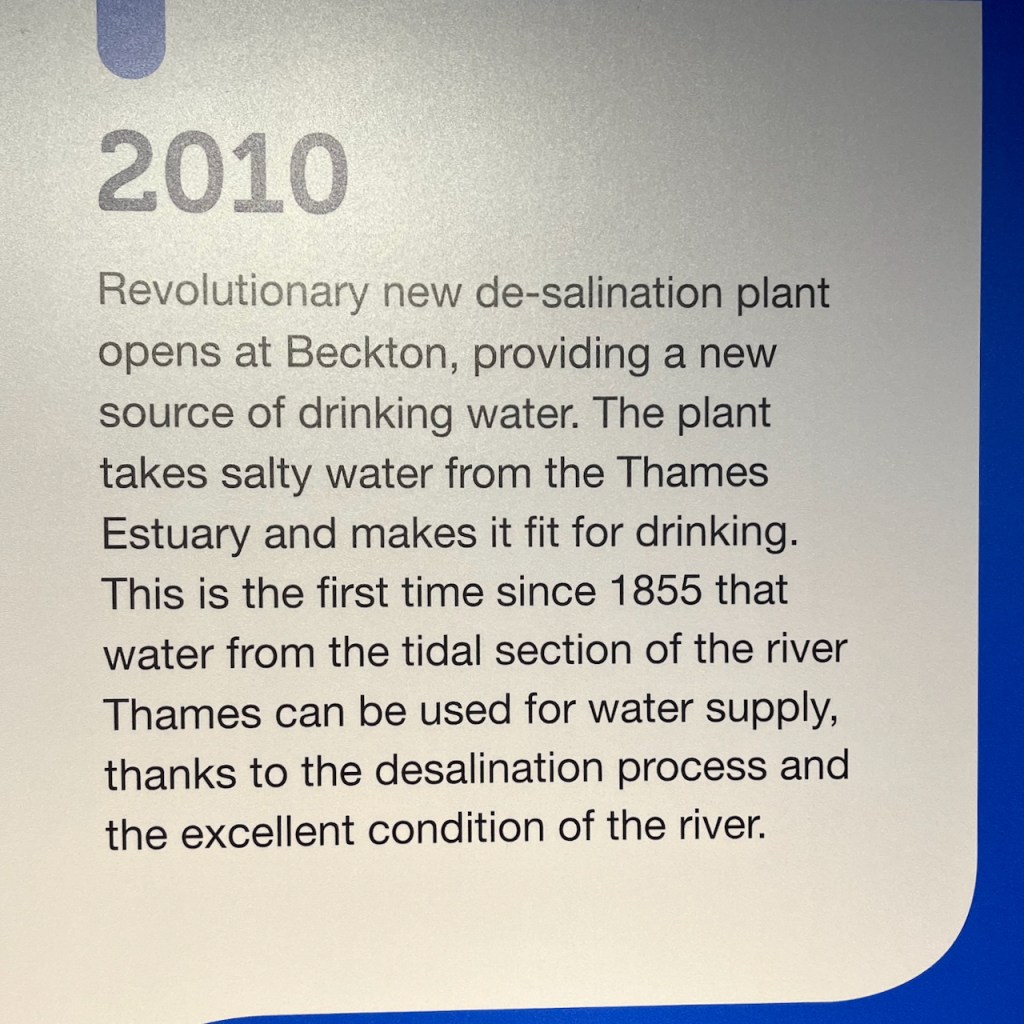

As well as history, I learned about today’s drinking water.

For example: did you know that 10% of London’s drinking water is de-salinated water from the Thames estuary? The “revolutionary new de-salination plant” opened in 2010:

I watched a gripping – and somewhat alarming – video of heroic engineers cautiously making their way down soaking brick-lined pipes in the sewers below London streets. They were down there to inspect and clear blockages. I also saw the “rat” robots that can be sent down the smaller sewers – it’s a tough environment for technology.

As well as all this gripping factual information, there’s much of strange beauty in the machinery. I particularly enjoyed the devices and dials.

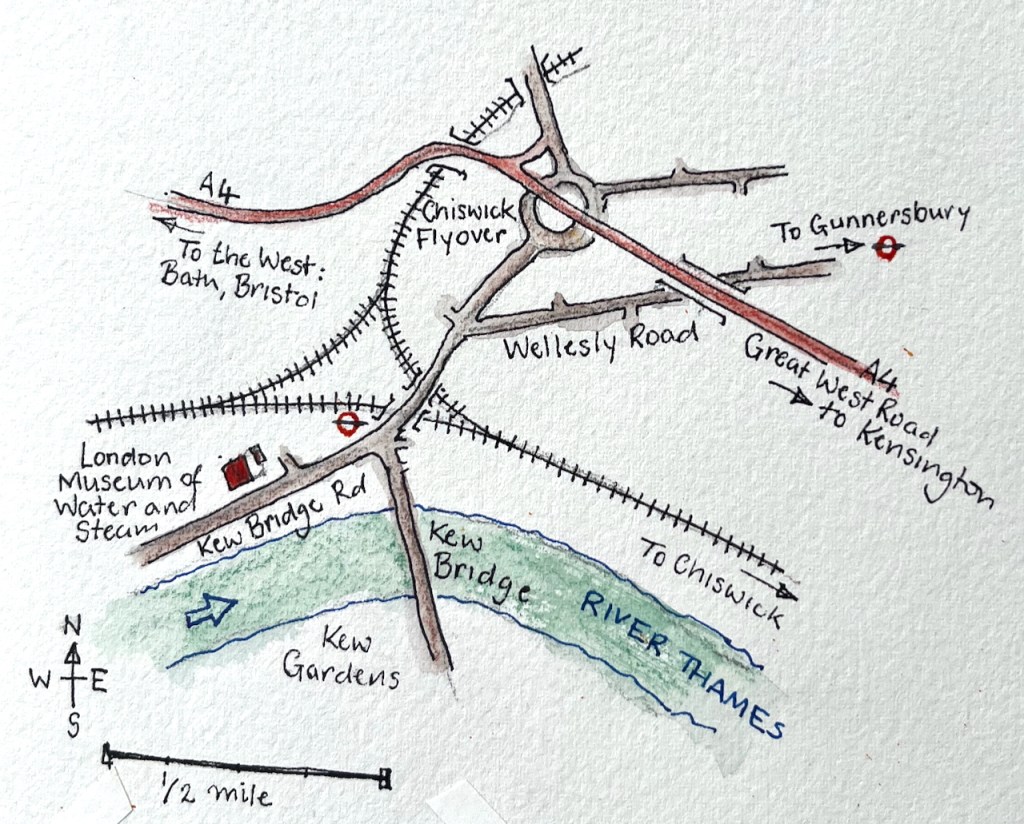

Definitely recommended. It’s on the underground. No café: take a picnic to eat at their indoor tables.

It closes at 4pm – I managed to do the sketch from the garden, just before they closed the gates.

I added the colour later.

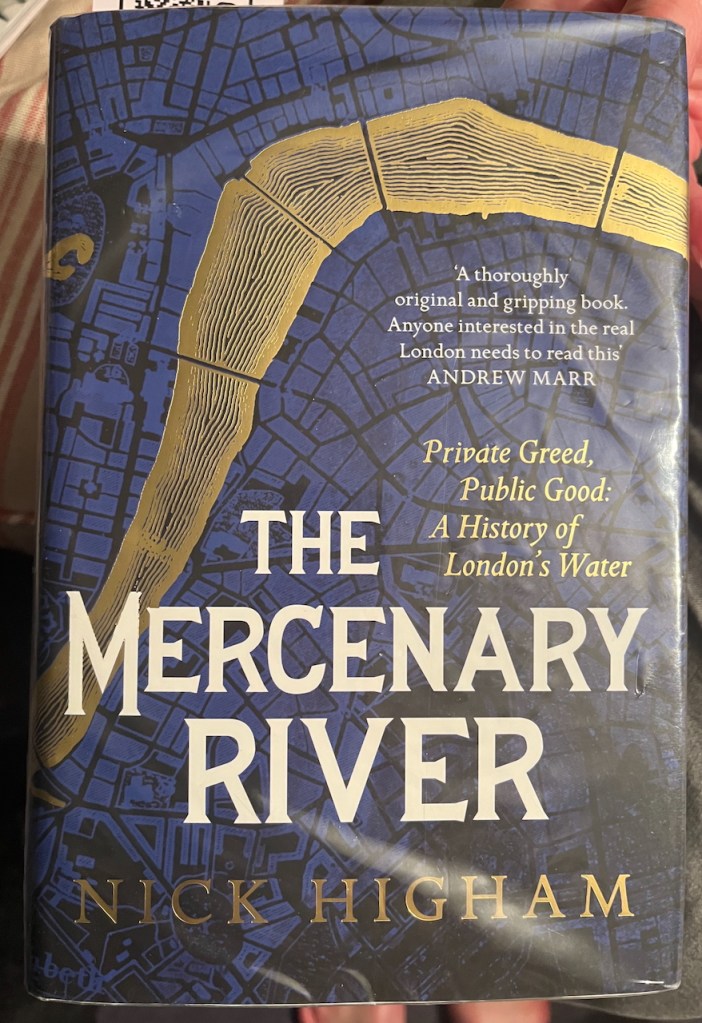

Information in this post is from placards in the museum or from their website. Inspired by my visit to the museum, I read this excellent book about London’s water supply: