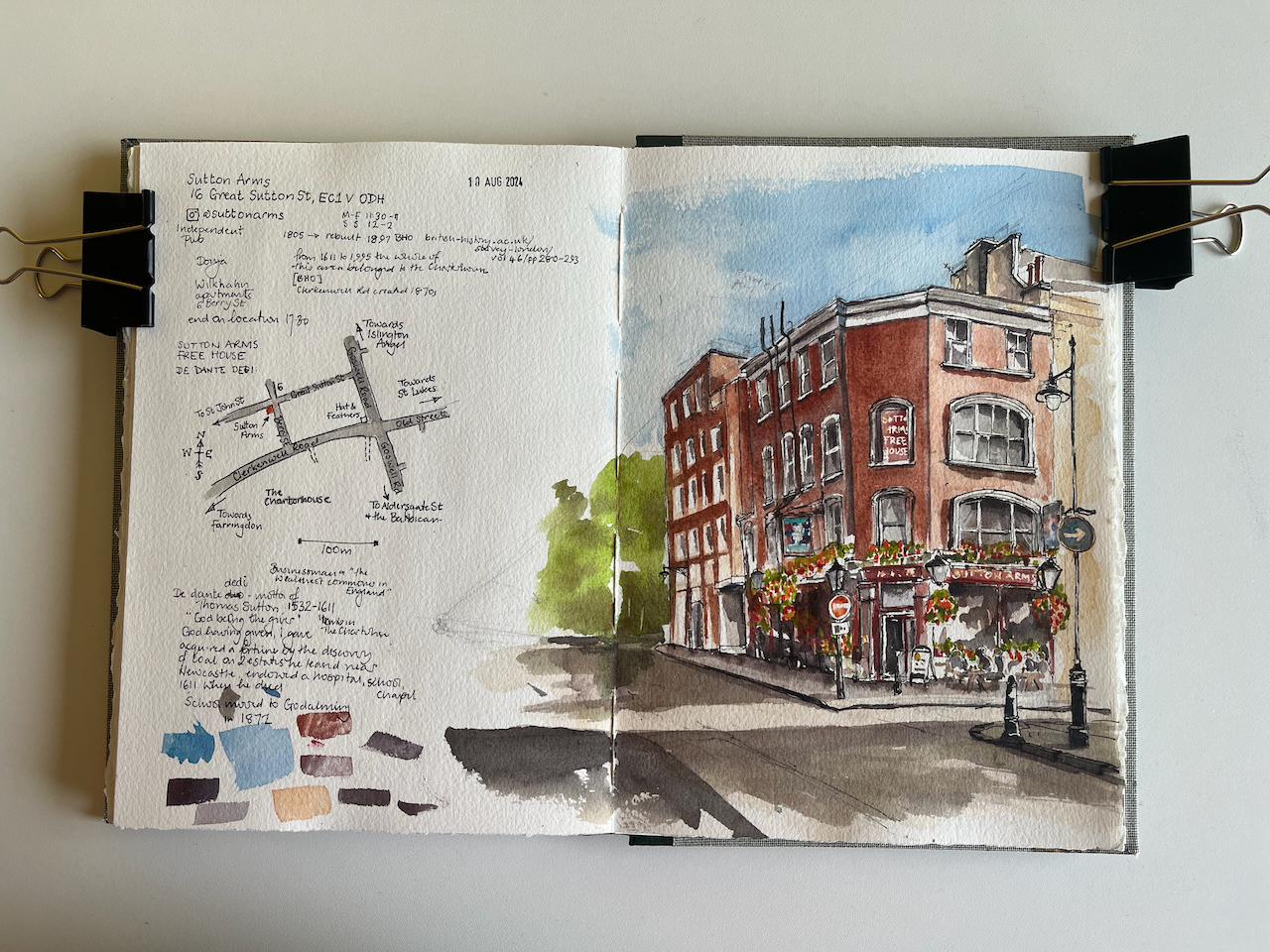

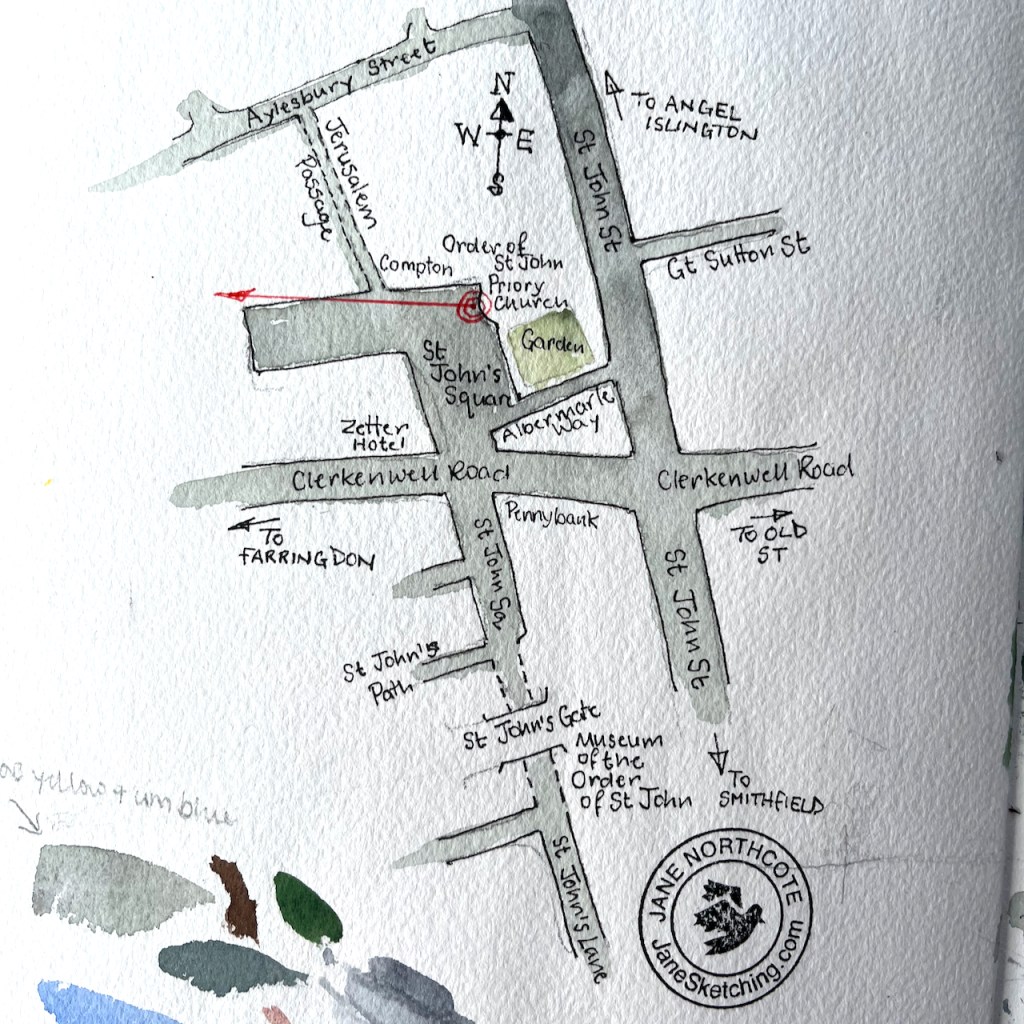

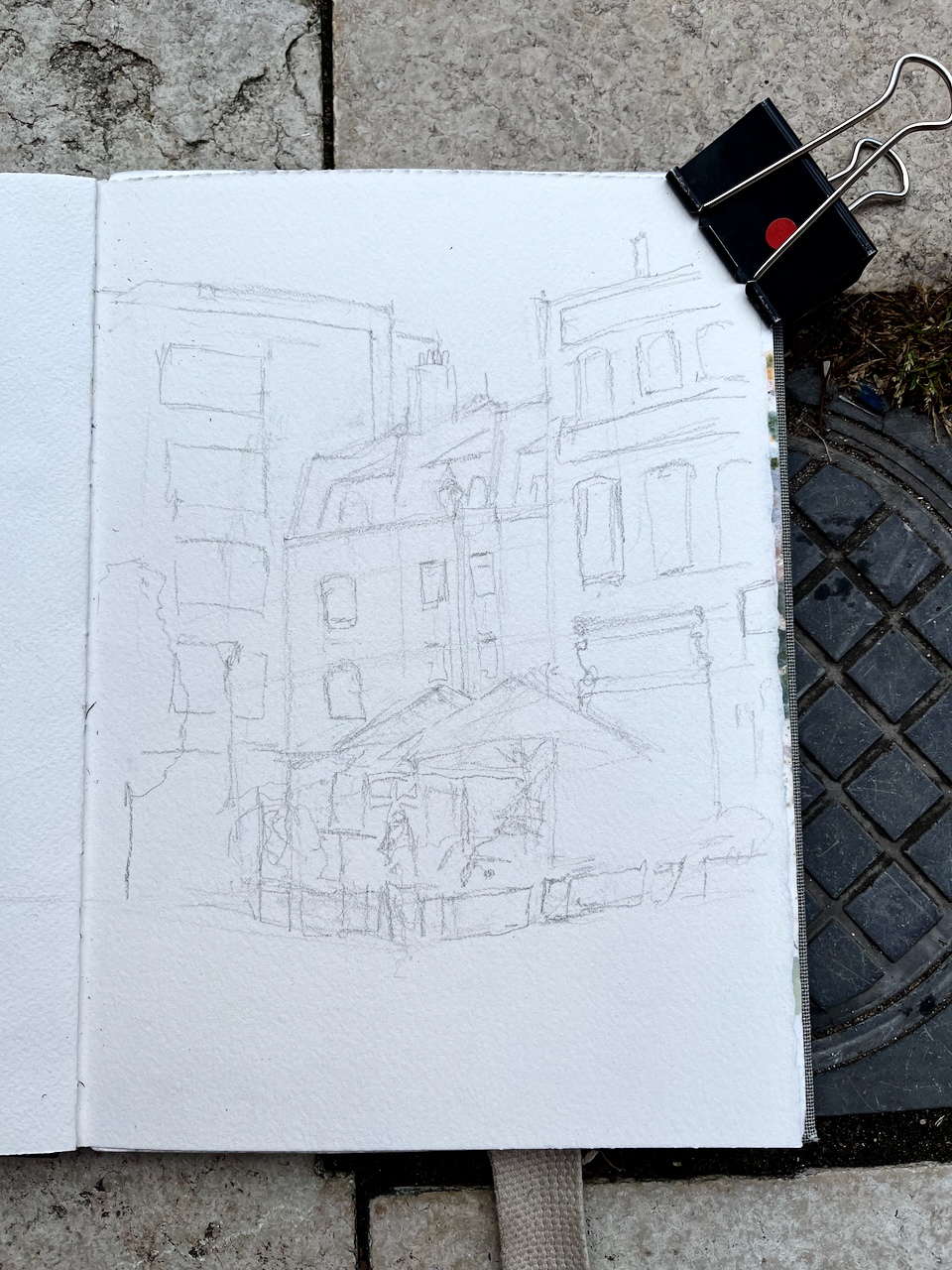

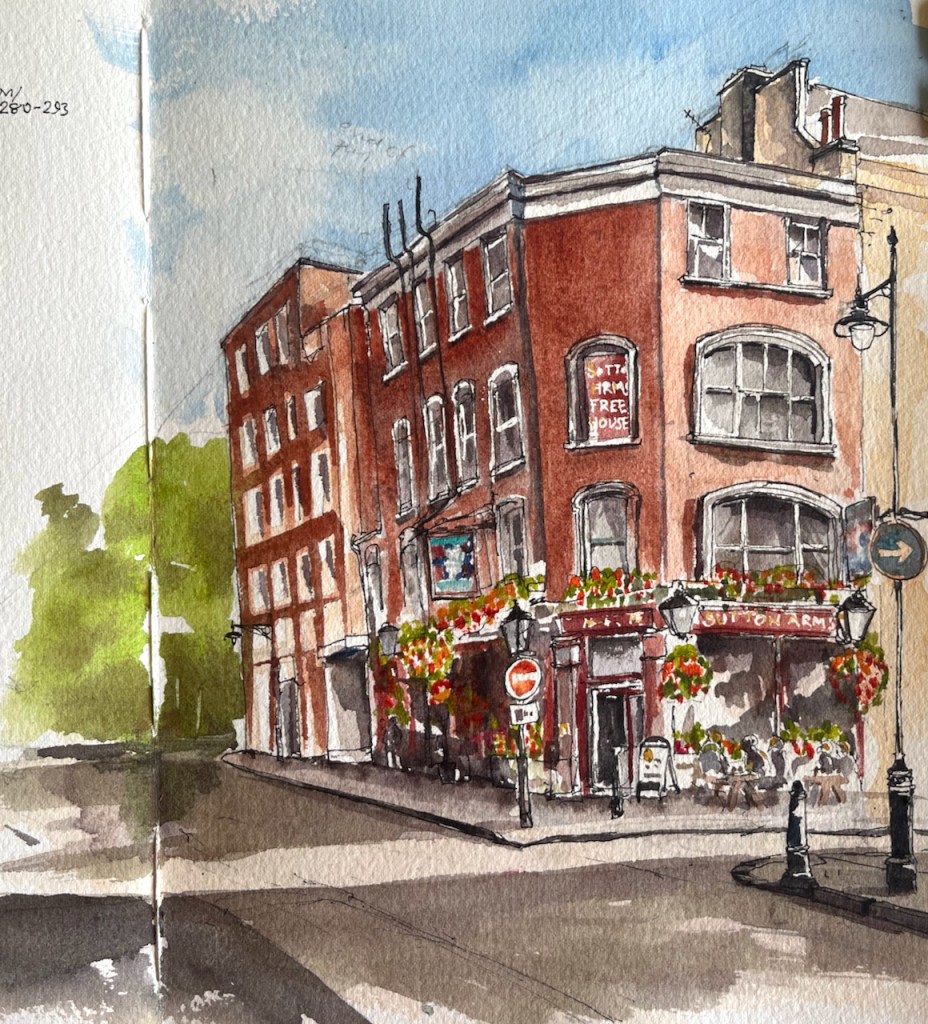

This is the Sutton Arms in Clerkenwell, 16 Great Sutton Street, EC1.

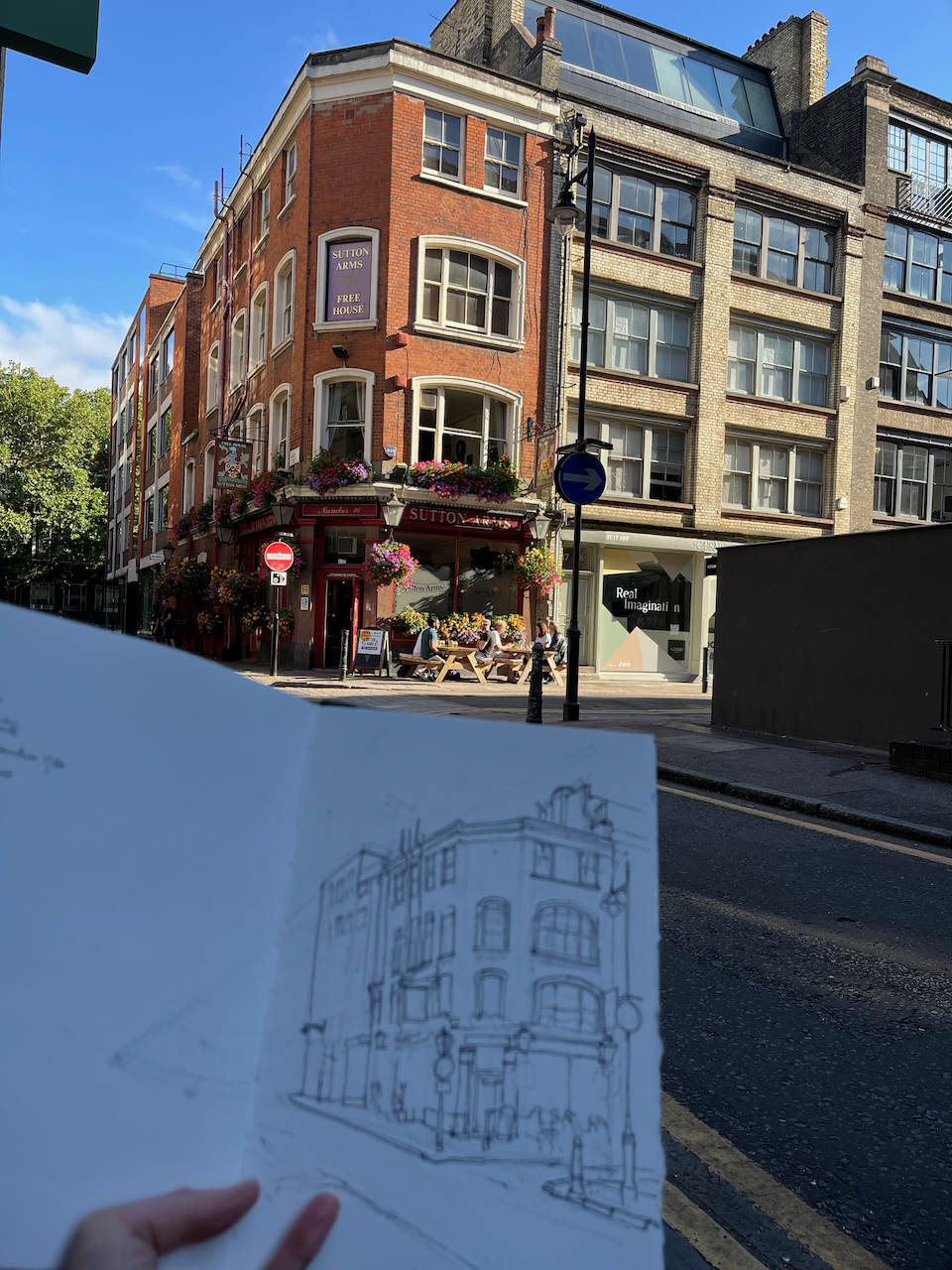

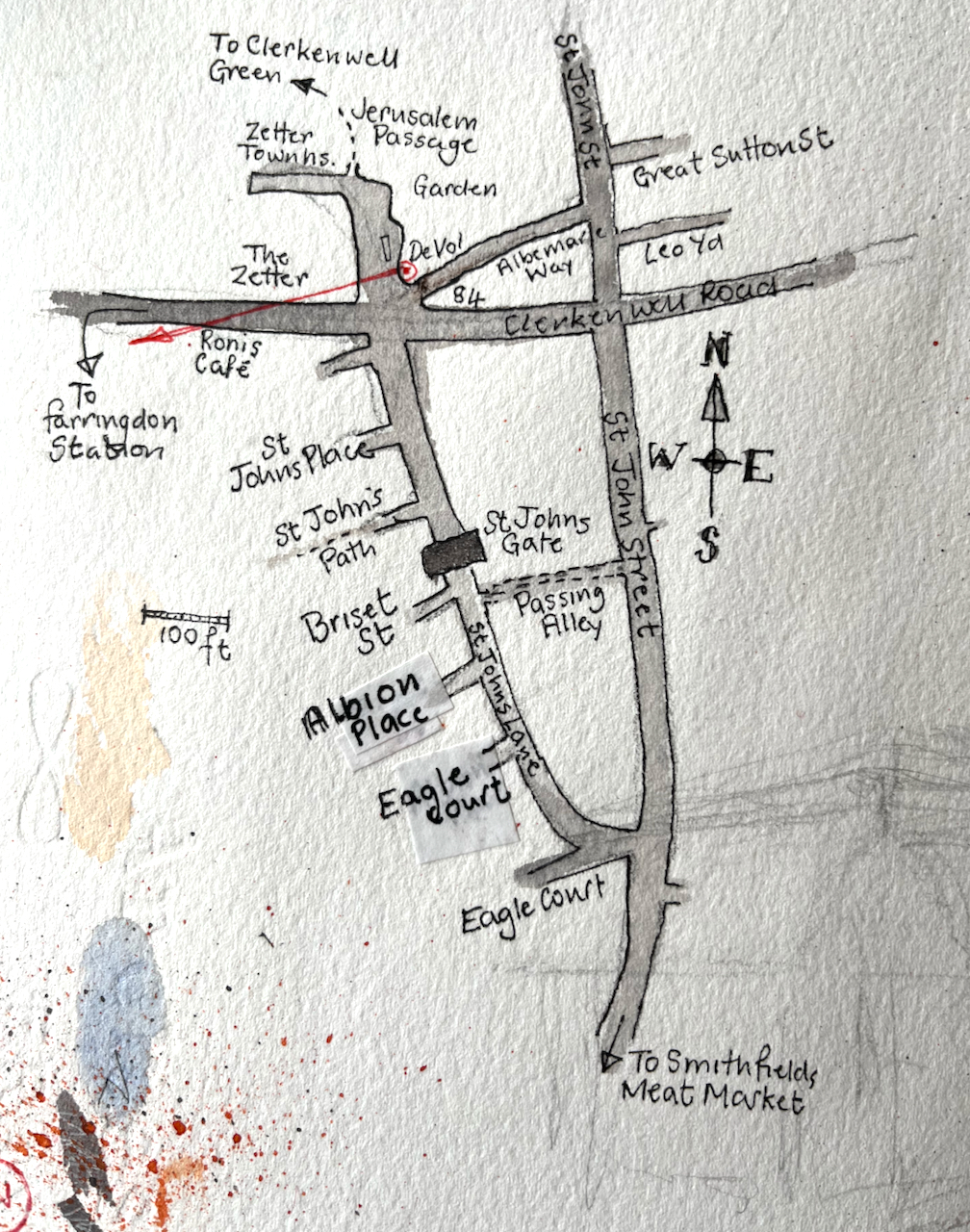

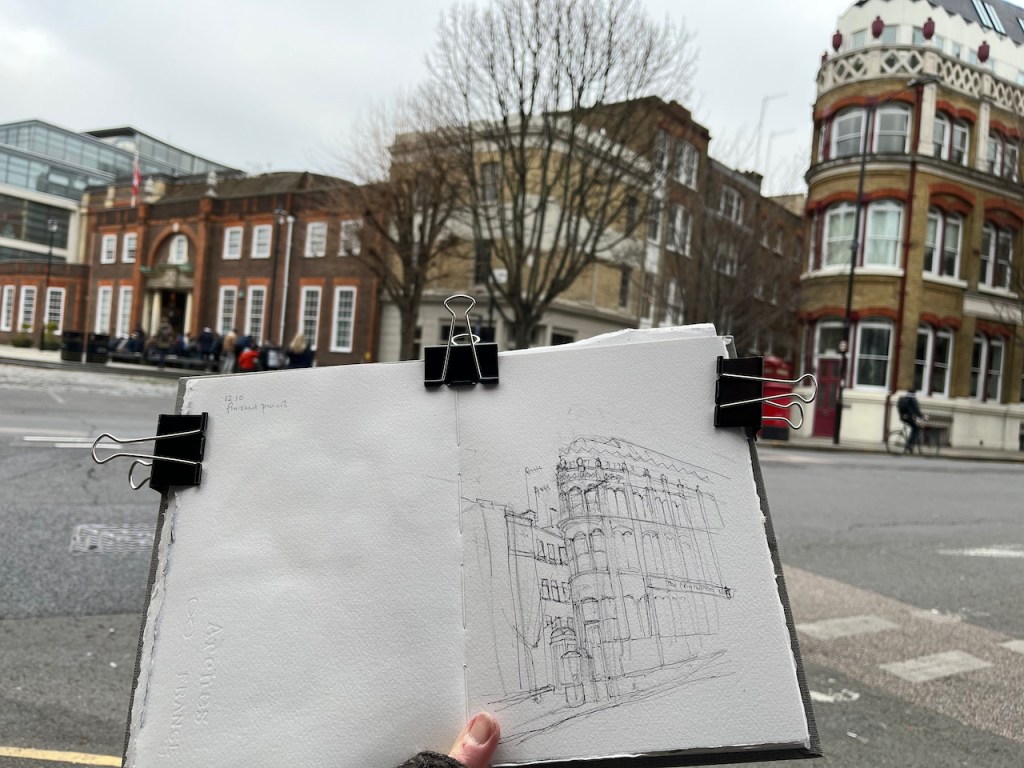

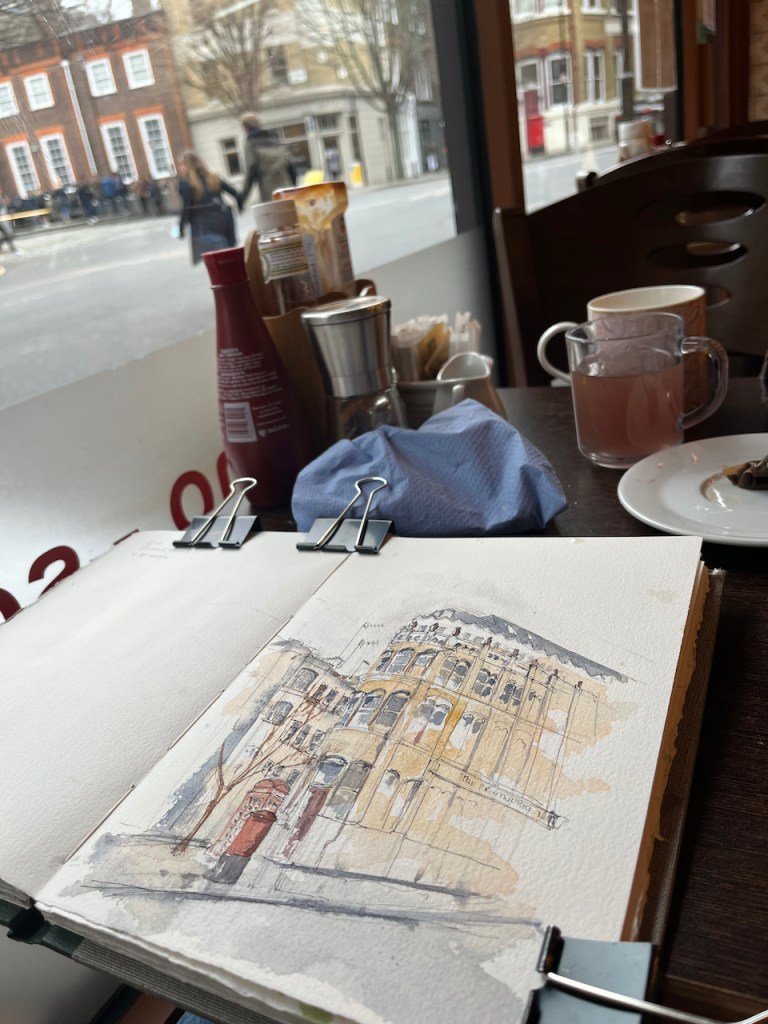

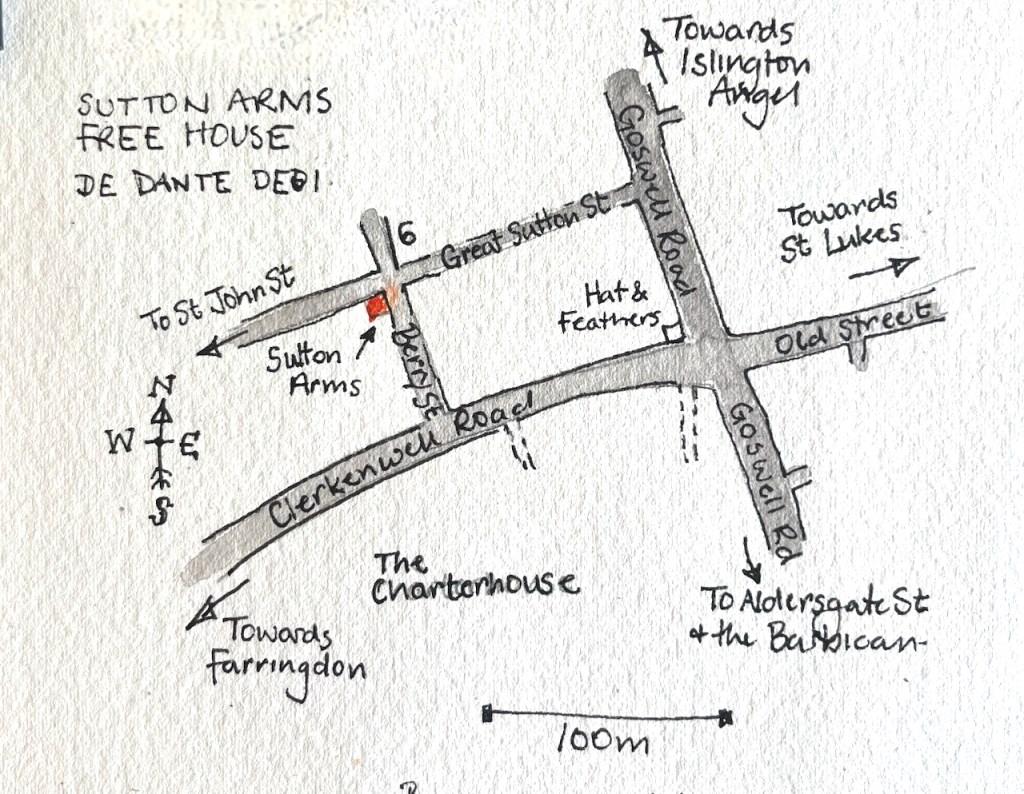

I sketched it towards the end of a sunny afternoon in August, sitting on steps outside number 6 Berry Street. As you see, the sun streamed in from the west. The trees in the distance, on the left of the drawing, are on Clerkenwell Road. Behind them is The Charterhouse, fulfilling its ancient tradition as an arms house and sanctuary for the elderly and frail.

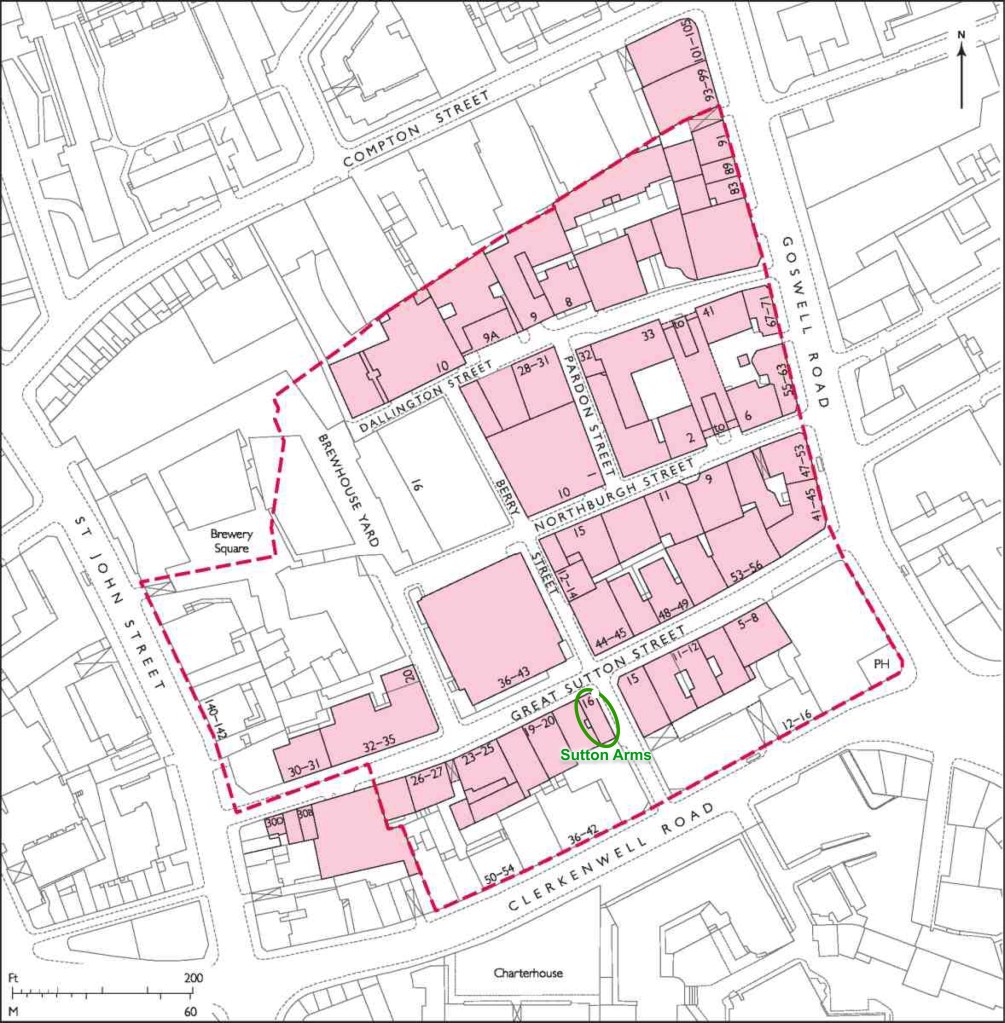

From 1611 to 1995, The Charterhouse owned the whole of this area.

The Charterhouse sold this land in 1995. A developer bought up the land and built factories and warehouses. In the 21st century a new wave of developers transformed former warehouse blocks into apartments and offices. I sketched sitting outside one such: 6 Berry Street is residential apartments. This is now an area for architects and interior designers.

There was a pub here by 1825 [1]. It was rebuilt in 1897 [2]. It’s now a Free House. It’s clearly well looked after and well patronised. Definitely to be visited! The flowers are spectacular.

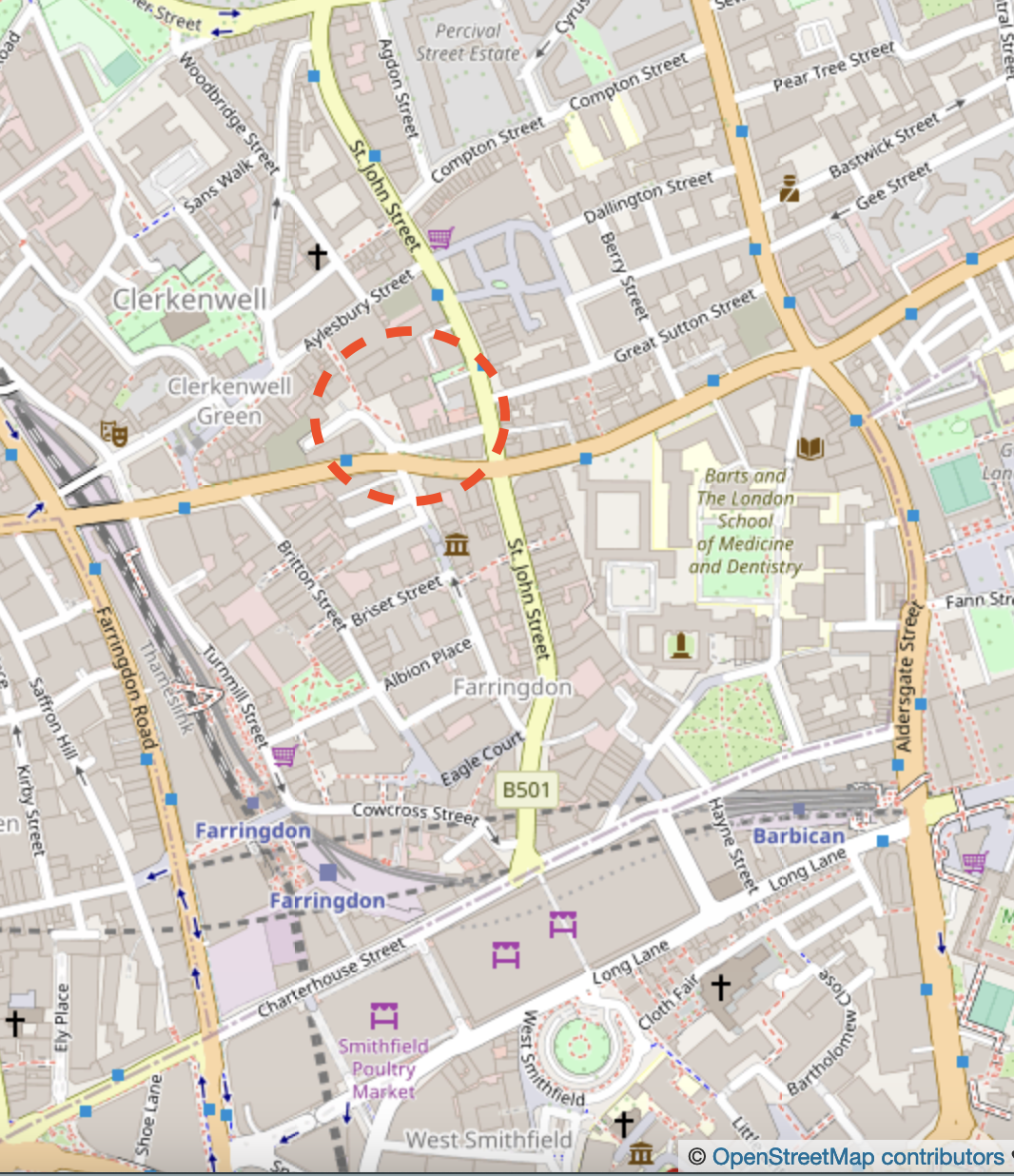

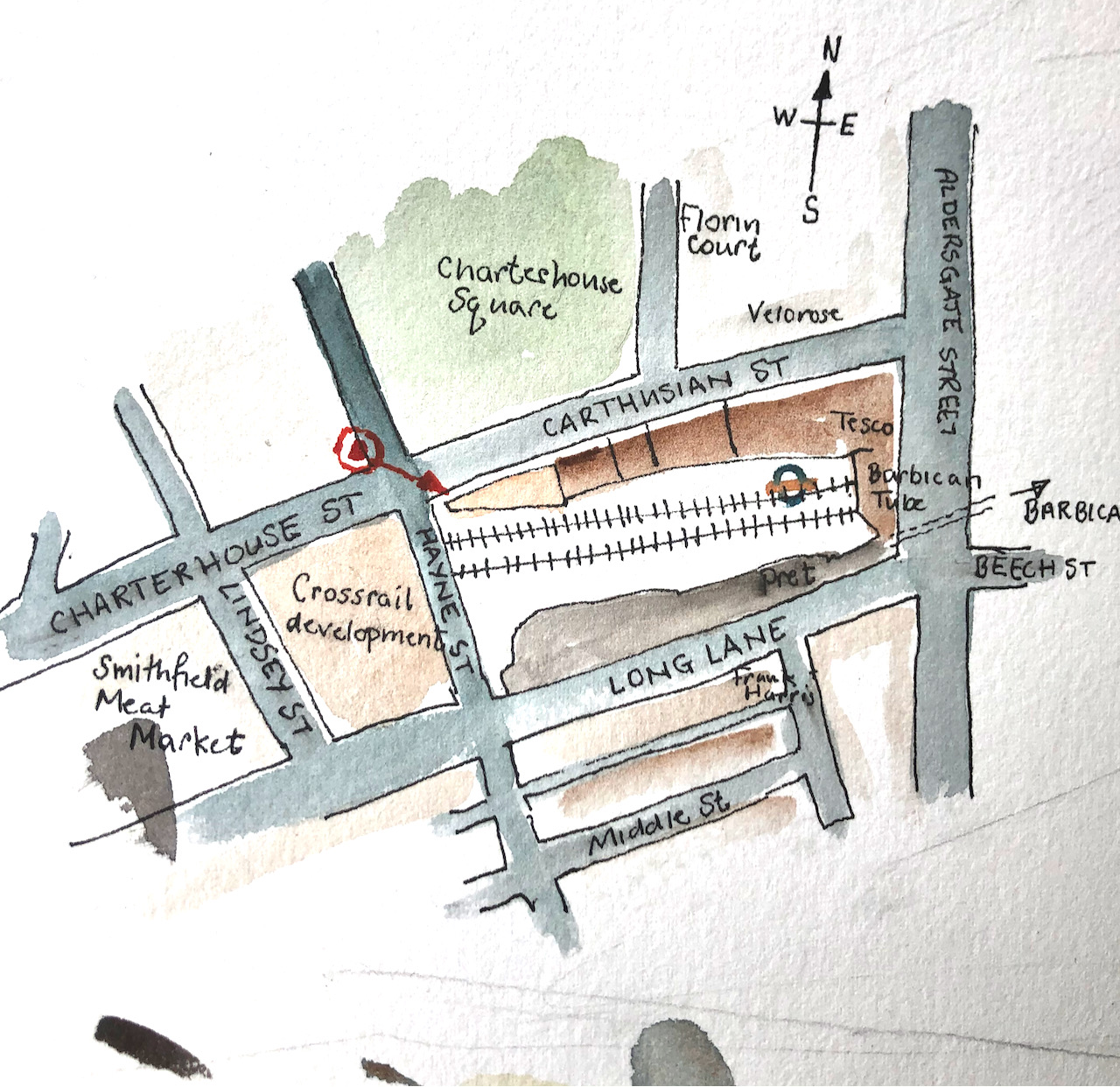

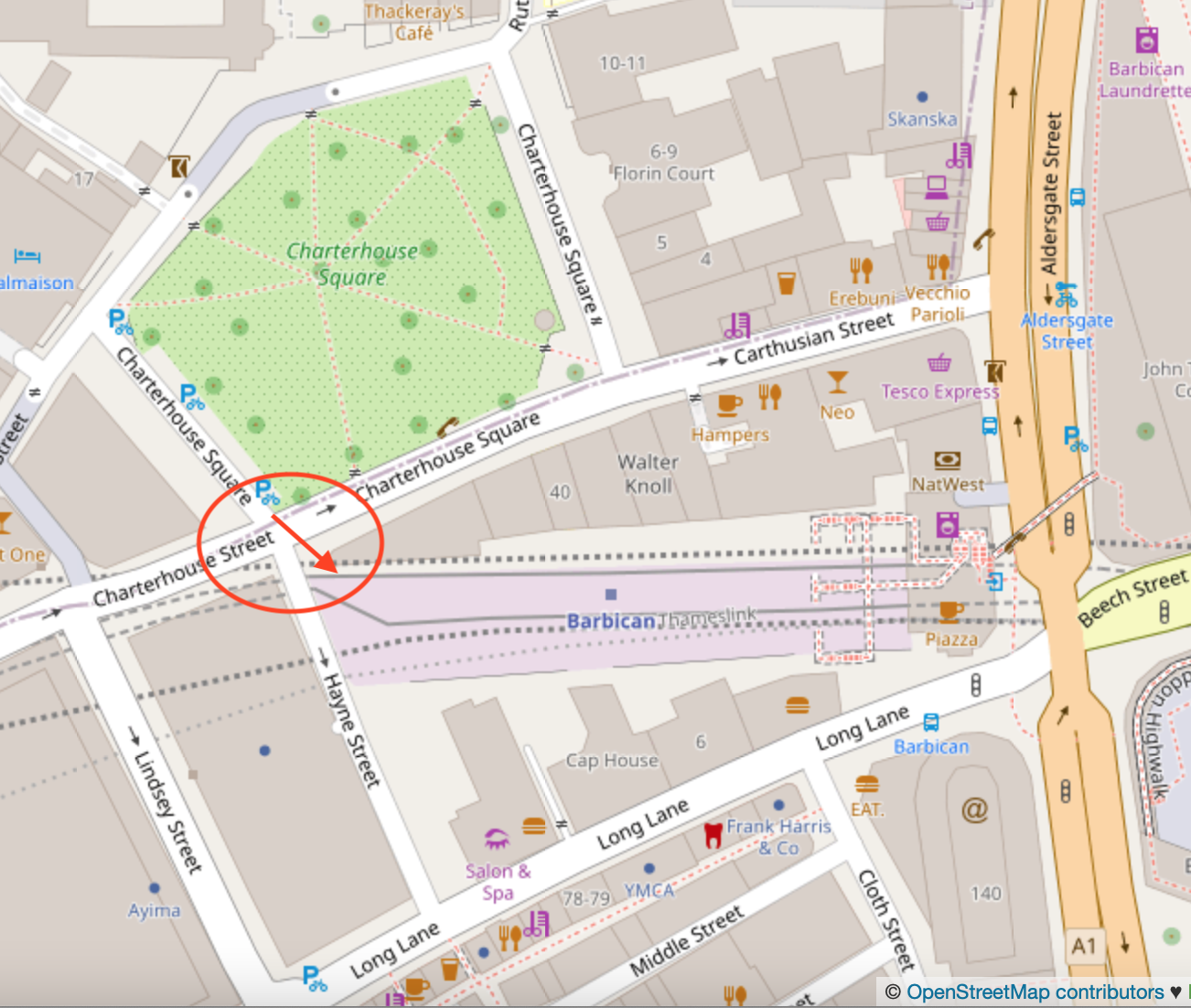

Thomas Sutton (1532-1611) was the founder of the Charterhouse, hence the name of the road and the name of the pub. This is the Sutton Arms in Clerkenwell, north of The Charterhouse. There is also a Sutton Arms south of The Charterhouse, in Carthusian Street, near Barbican tube.

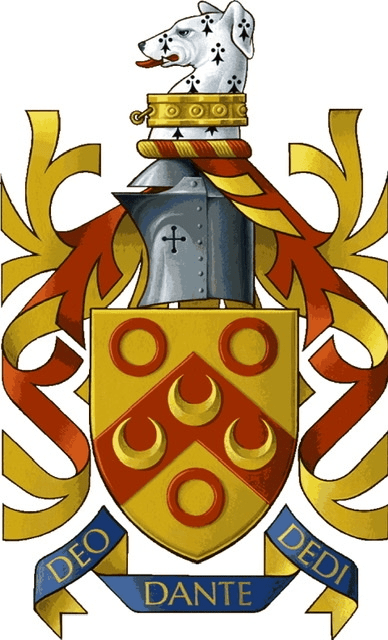

The pub sign is Sutton’s coat of arms. His motto is:

DEO DANTE DEDI

The translation is “God having given, I give”, or

“As God has given to me, so I give in my turn”,

a good motto for the benefactor that he was. The pub sign misses off the “O” in DEO and the “I” in DEDI.

The “Survey of London ” [2] gives a detailed history of this area, which has alternately flourished and decayed over the centuries. It is currently flourishing.

I completed the ink on location and finished the colour at my desk. The colours are:

- Fired Gold Ochre (bricks)

- Ultramarine Blue and Phthalo Blu (Green shade) (sky)

- Serpentine Genuine (trees)

- Mars Yellow (road and bricks)

- Ultramarine Blue plus Burnt Umber (blacks and greys)

- Transparent Pyrrole Orange (flowers, street signs)

The changing fortunes of the Great Sutton Street area.

In the 14th century this area was fields, owned by a Carthusian Priory. There was a mortuary chapel, called “Pardon Chapel” for saying the last rites for criminals and suicides.

Henry VIII eradicated the Carthusian Priory in 1538 (“Dissolution of the Monasteries”) and it passed into private hands, along with the land. It became known at “The Charterhouse”.

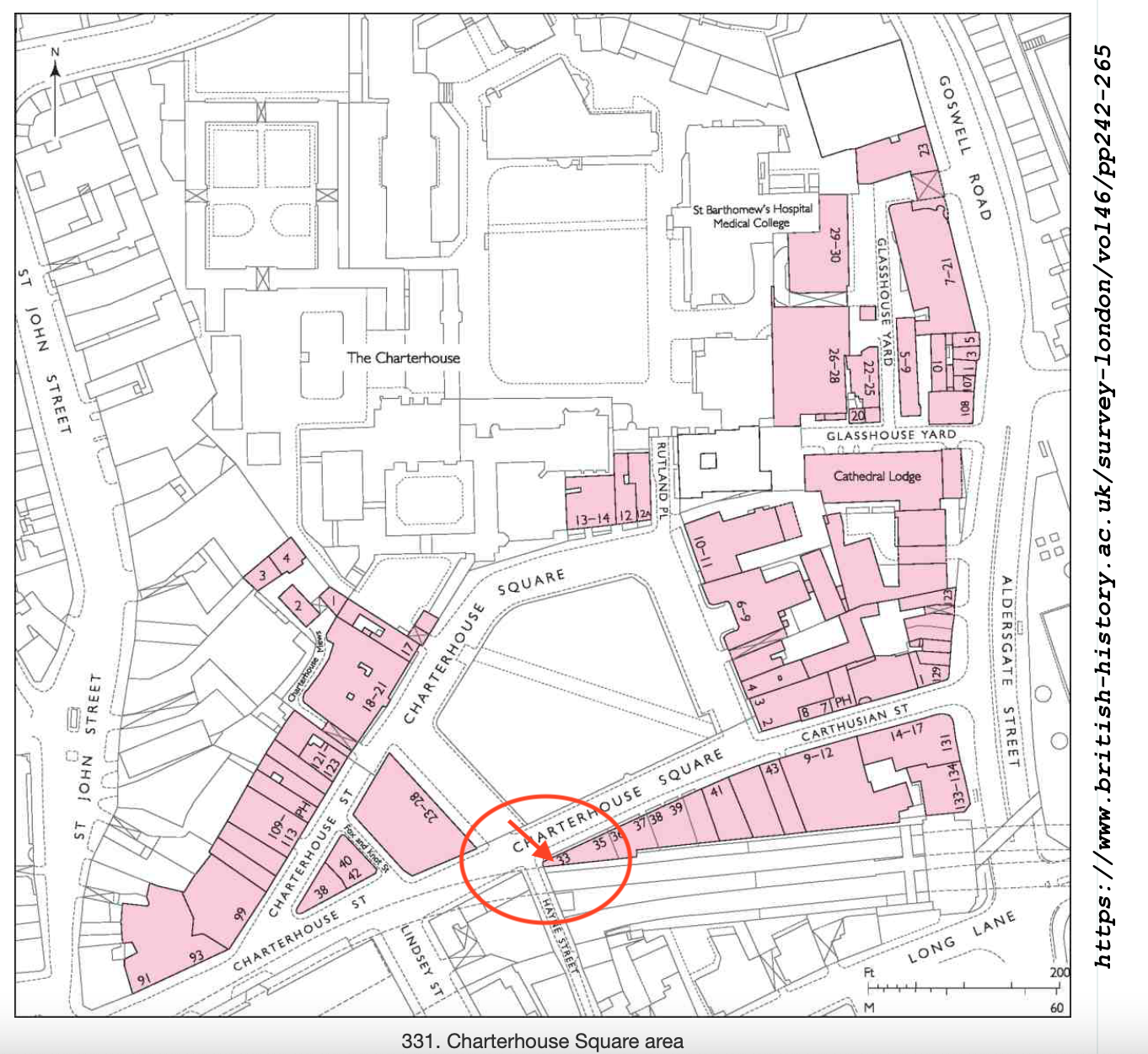

Thomas Sutton, a wealthy businessman, bought the Charterhouse in 1611. He died that year. His will provided for the hospital and almshouse that are still there. The Charterhouse leased the land outside its walls to developers, who built houses.

“By 1687, when the Charterhouse estate was thoroughly mapped by William Mar, almost the whole had been laid out in streets of small terrace houses—242 houses in all, with yards, gardens and sheds.” [2] These terraces set the street pattern for the small streets that are there today. The lattice continued to the walls of The Charterhouse. Clerkenwell Road was cut through much later, in the 1870s.

Then commerce moved in and a hundred years passed. By the 1700s, the area was a mix of residences and industries: “In 1731 Philip Humphreys, the Charterhouse gardener [..]complained of the adverse effect on his crops of smoke ‘from so many neighbouring Brewhouses, Distillers and Pipe-makers lately set up’ in the vicinity.” Thus we see that NIMBYism is not a new phenomenon.

A new developer (Pullin) came in and rebuilt, and more and larger factories were built. Again, the neighbours complained: “Already by the 1820s some houses were giving way to further industrial developments, including slaughterhouses, a dye-house, breweries, and vinegar, vitriol and gas works. Complaints were made to the Charterhouse in 1832 about the nuisance of these works and their steam engines, and to the Vestry in the 1850s about the ‘boiling of putrid meat and other offal’ and blood running into the drains.”

Building continued.

Eventually government intervened: “Extensive redevelopment of the Charterhouse estate followed remarks in 1884–5 by the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes as to the badness of the houses there. […] Charterhouse was criticized for allowing [..]the incidence of house-farmers, severe overcrowding and badly constructed, poorly ventilated housing to continue on its property. One house in Allen Street was found to be occupied by thirty-eight people, eleven of them in one small room; similar conditions were found in the cottages of Slade’s Place. Many of these properties were occupied by costermongers with ‘very precarious’ earnings (whom the Commission felt would do better ‘if they kept from drink’).[2]”

The Charterhouse governors eventually took action. The small houses were demolished, and replaced by factories and warehouses. This time the trades were less polluting: “Among early occupants were clothing manufacturers: milliners, mantle-makers and collar-makers, leather manufacturers, glove-makers and furriers. The printing trade was also well represented, along with book-binding, engraving and stationery manufacture. Continuing a long-standing tradition were several butchers and tripedressers.” By now we are in the early 1900s.

About a dozen buildings were destroyed by bombing in the 1939-45 conflict, and replaced in the 1950 and 1960s by factories and warehouses.

The Survey of London [2] reports that the area was “considerably run down” in 1995 when the Charterhouse sold it to developers. The developers started a programme of warehouse conversions, to apartments and offices, which transformed the area, and moved it back upmarket. And that’s where we are today.

(The above is my summary of the more detailed description in reference [2])

[1] List of licensees in

https://londonwiki.co.uk/LondonPubs/Aldersgate/SuttonArms.shtml

First licensee recorded in their list is 1825.

[2] British History Online: ‘Great Sutton Street area’, in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple( London, 2008), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp280-293 [accessed 2 September 2024].

[3] History of The Charterhouse https://thecharterhouse.org/explore-the-charterhouse/history/