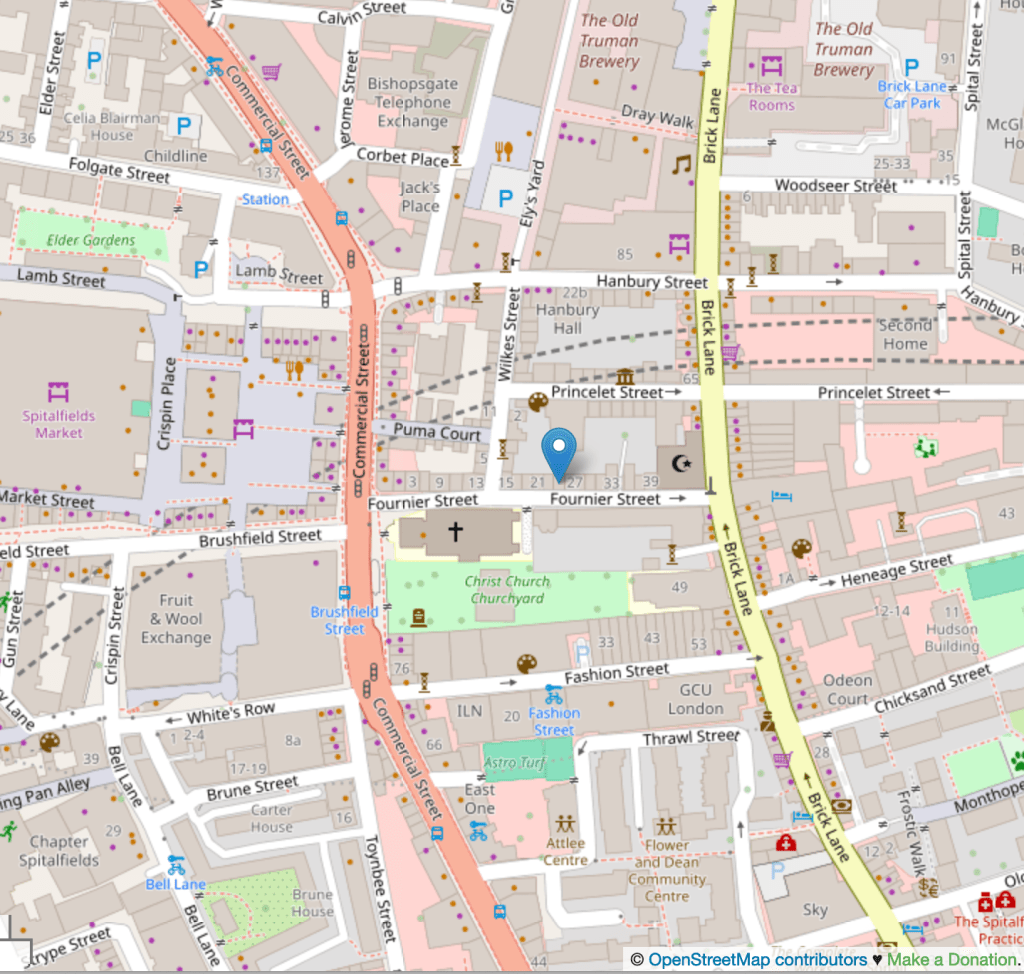

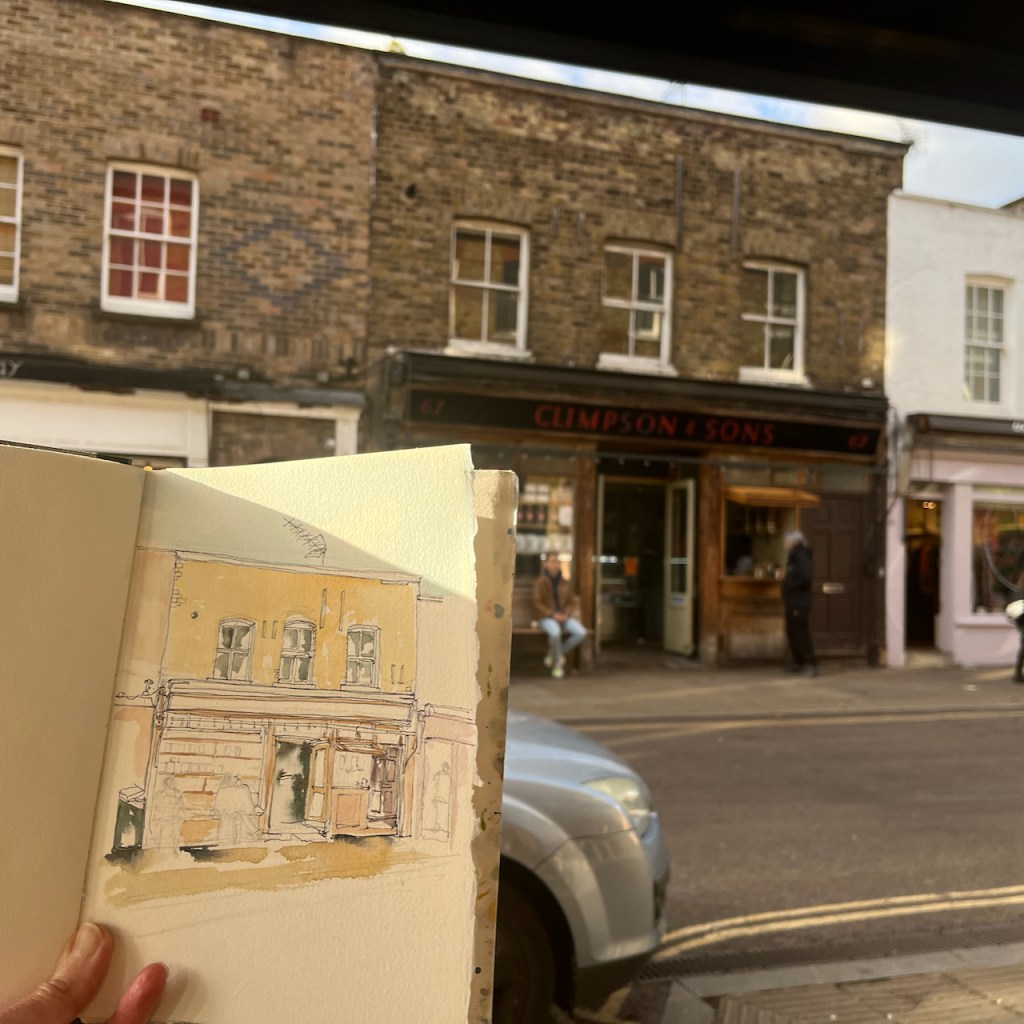

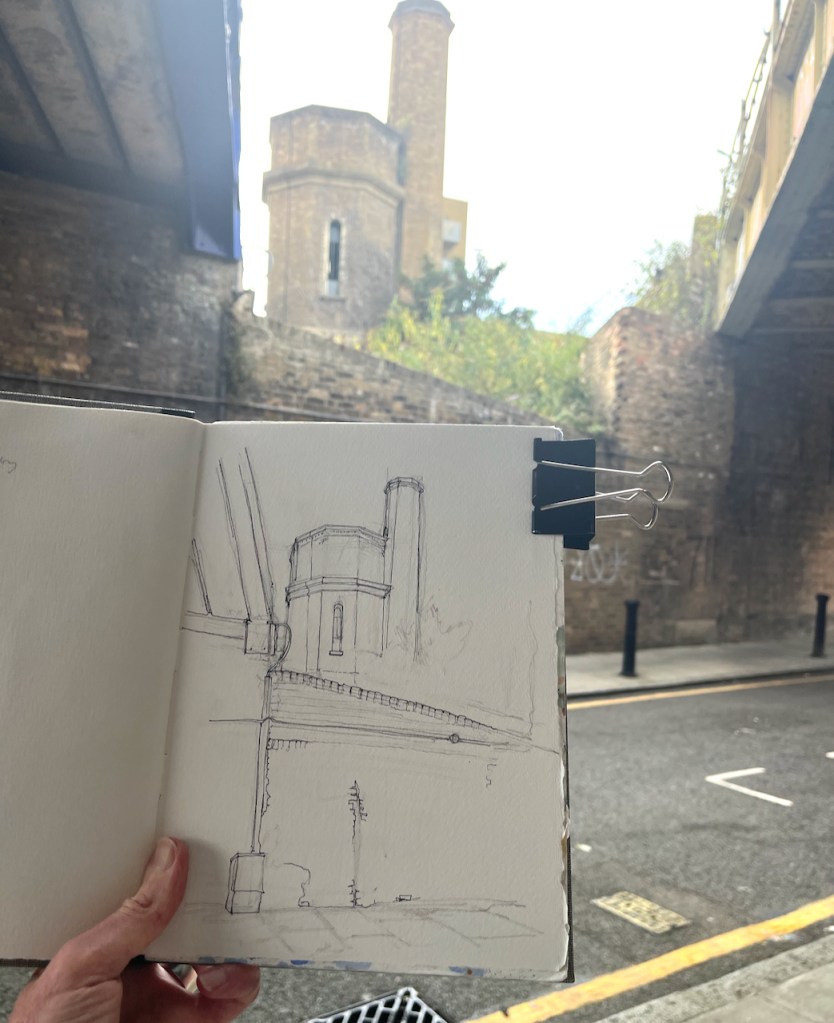

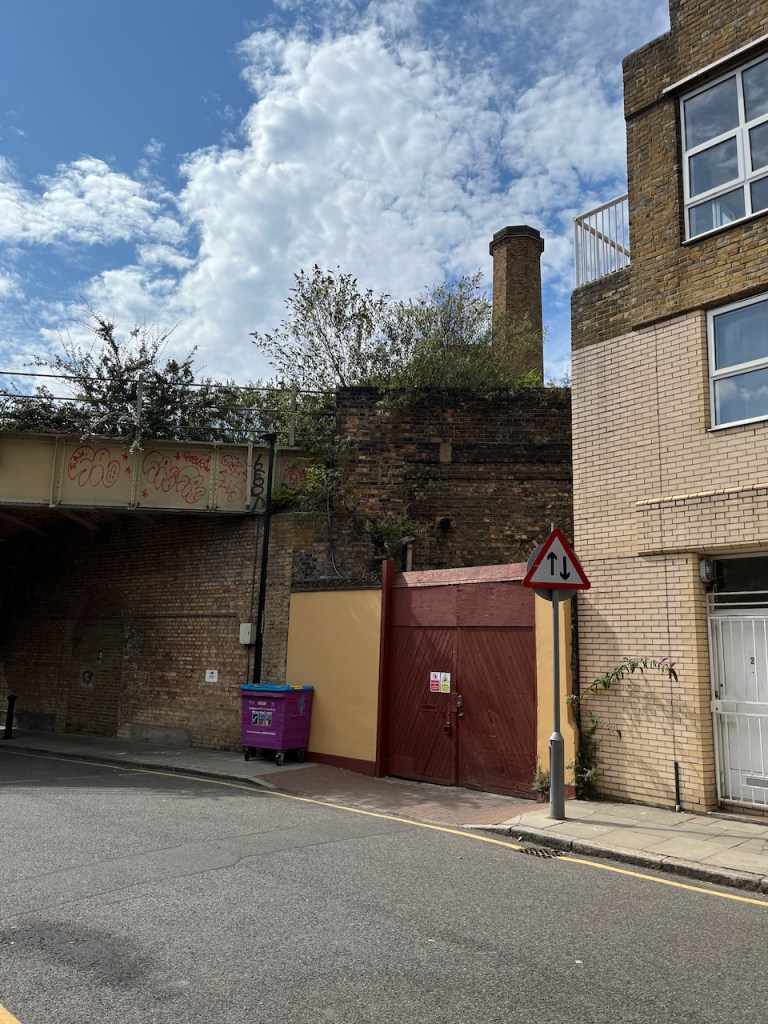

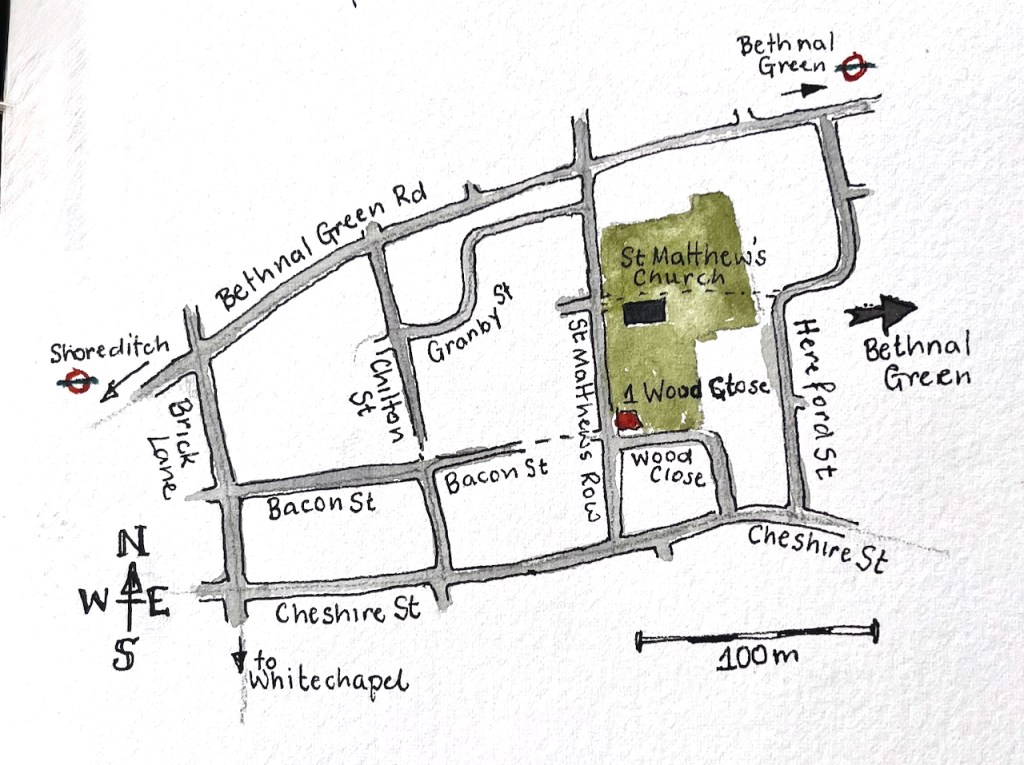

See this interesting building! It’s just a few hundred yards from Brick Lane in East London.

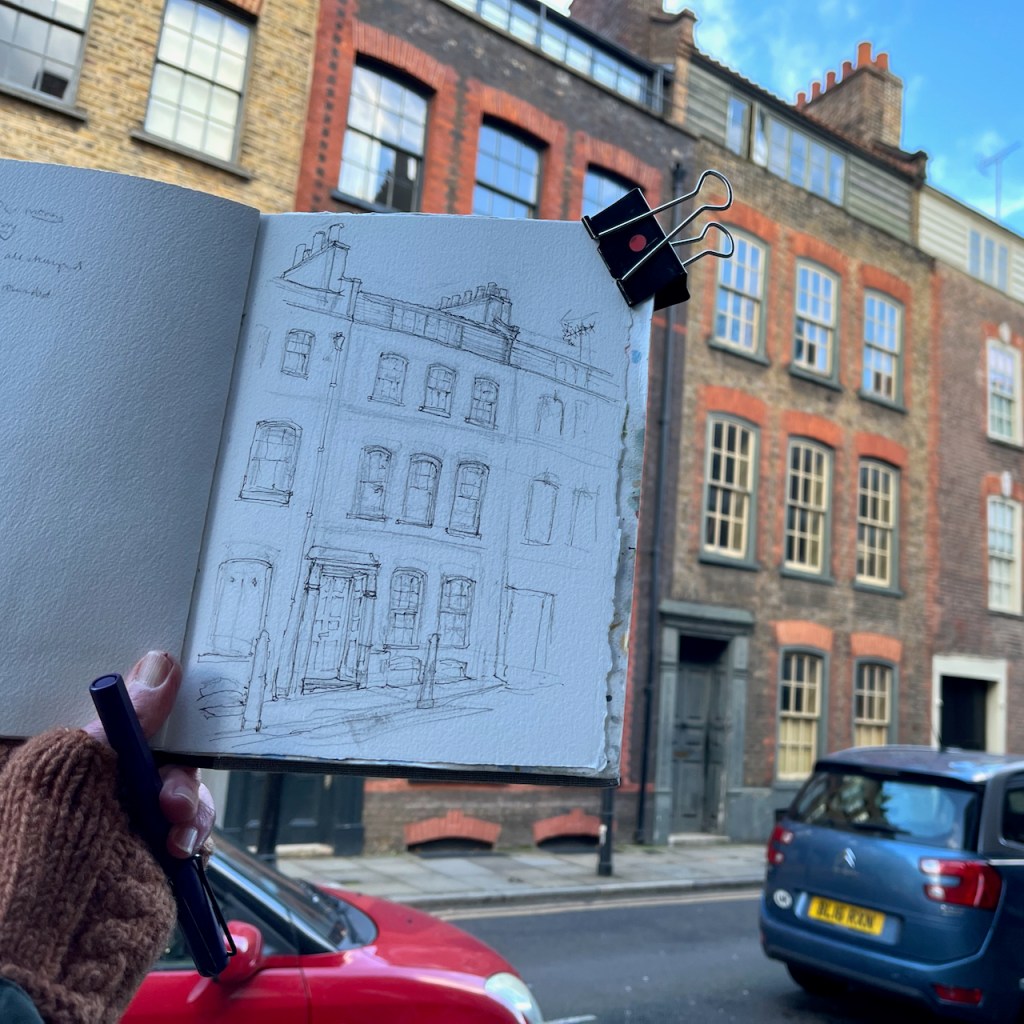

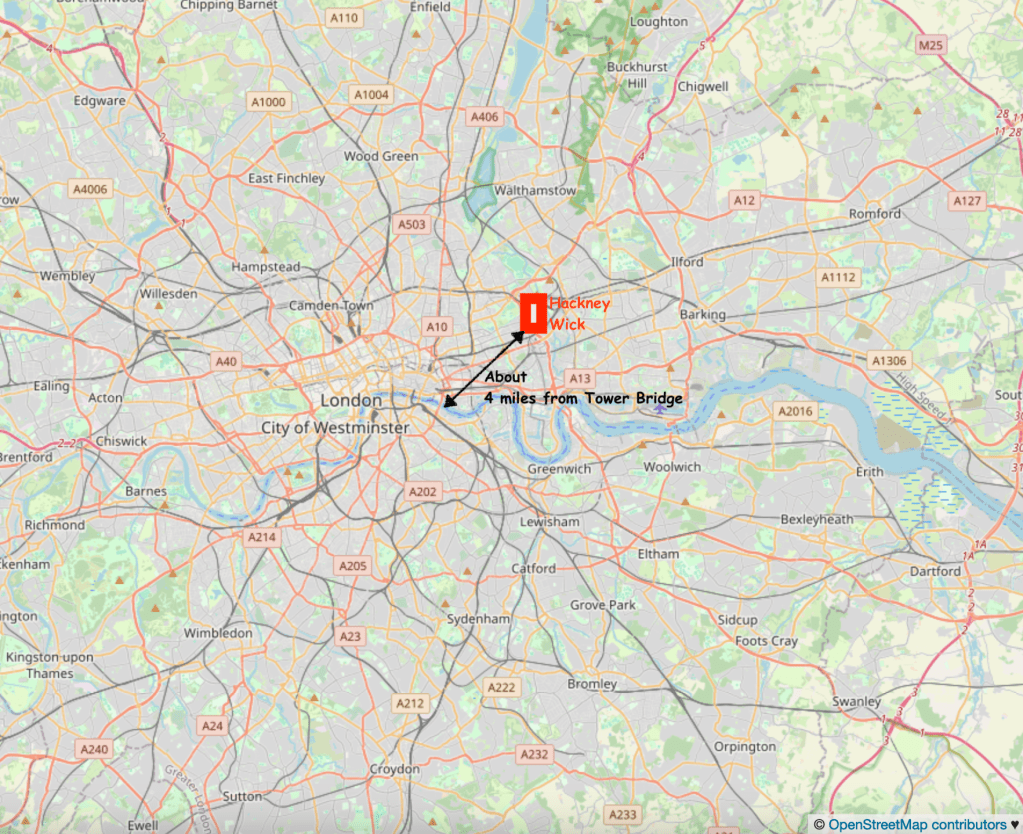

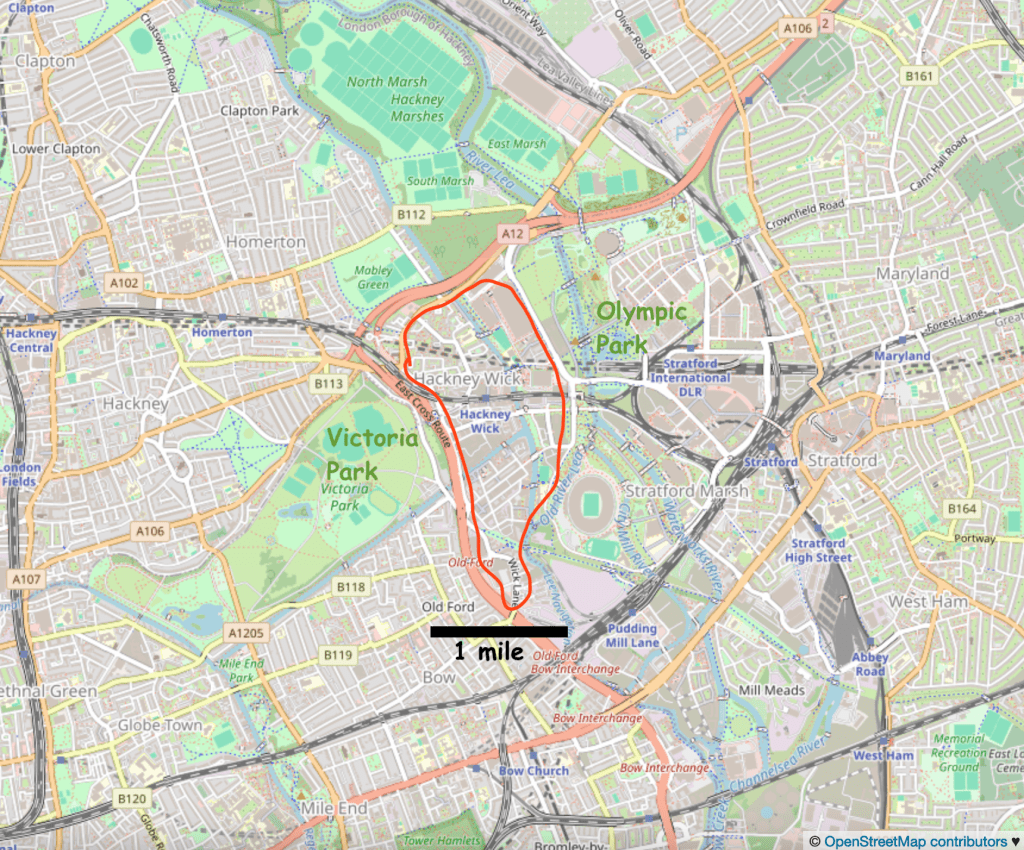

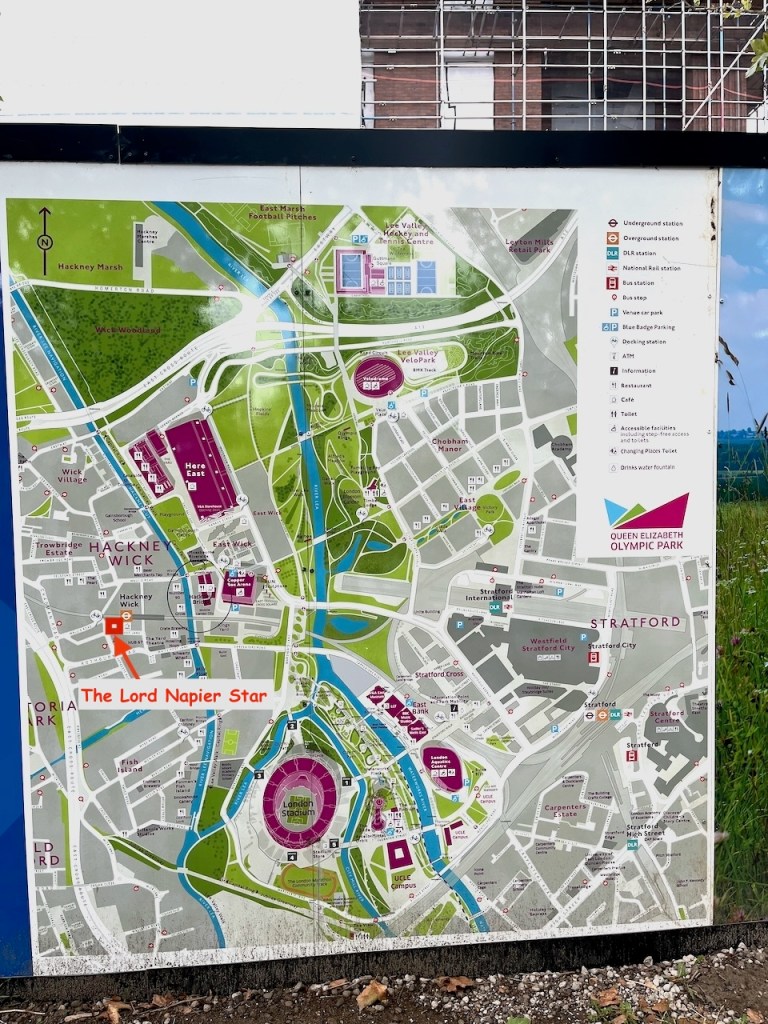

I’d walked past it a few days previously, when I had been taking a circuitous route through East London on the way back from Hackney Wick. It’s an unusual building for the neighbourhood, most of which is terraces or blocks of post-war flats. This building stood out, on its own, at a street corner. What is it doing there?

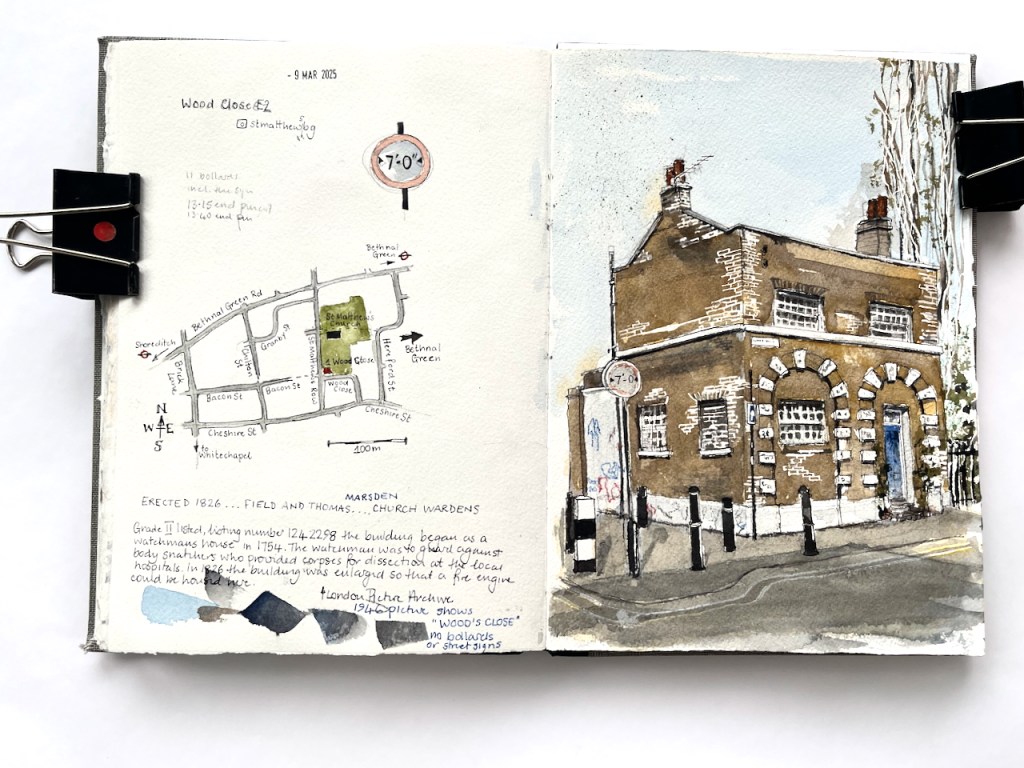

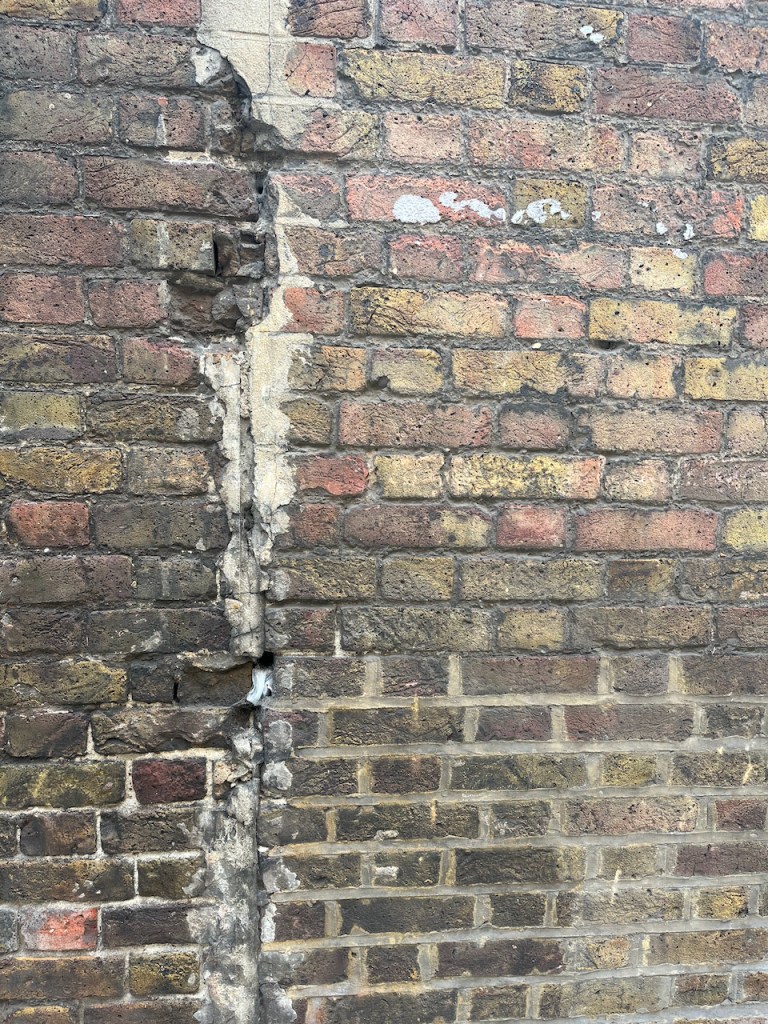

I went back a few days later for a closer look. On the white band at the front of the building I could decipher some words:

“ERECTED 1826 [something] FIELD AND THOMAS [something] CHURCH WARDENS”

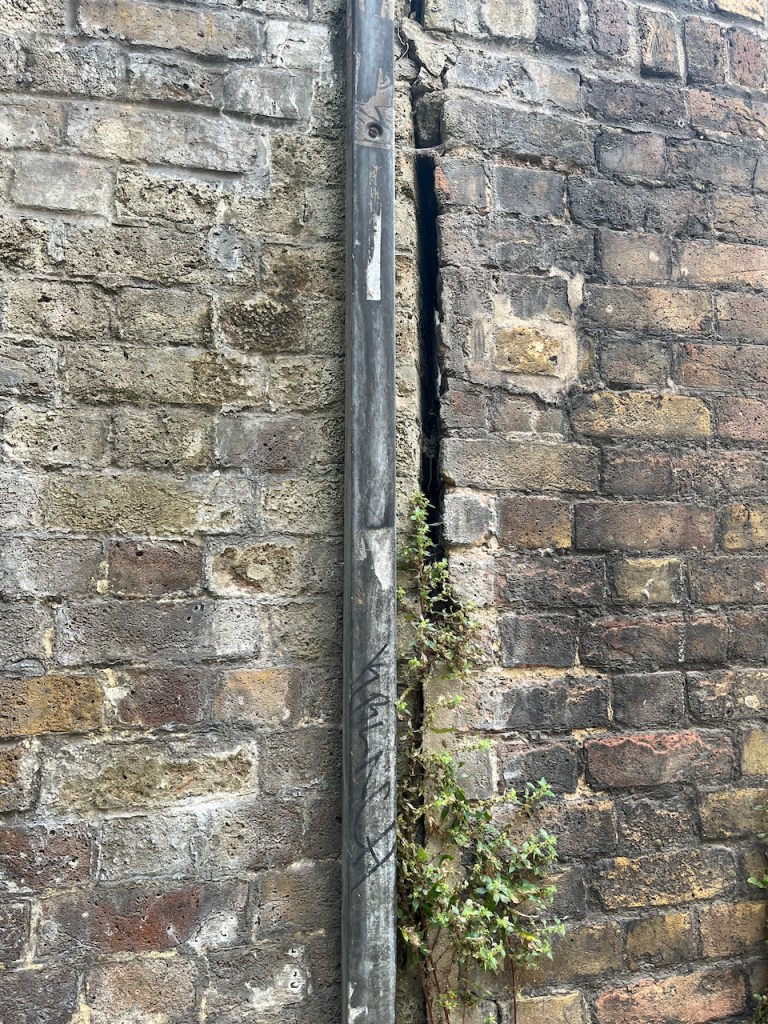

London Picture Archive has a photo of this building from 1946. The words on the front were a little clearer in 1946, so I can read that Thomas’ second name was MARSDEN. The London Picture Archive caption says that “the building began as a watchman’s house in 1754. The watchman was to guard against body snatchers who provided corpses for dissection to local hospitals. ” So that’s what it was doing: it was guarding the graveyard.

The London Picture Archive caption goes on to say that “In 1826 the building was enlarged so that a fire engine could be housed there.” That’s the building we see now, labelled 1826. It doesn’t look big enough for a fire engine.

In the London Picture Archive photo from 1946, the street name affixed to the building says “Wood’s Close” which would indicate it was named after someone called Wood. Today the street name on the building is “Wood Close”

This building is listed Grade II.

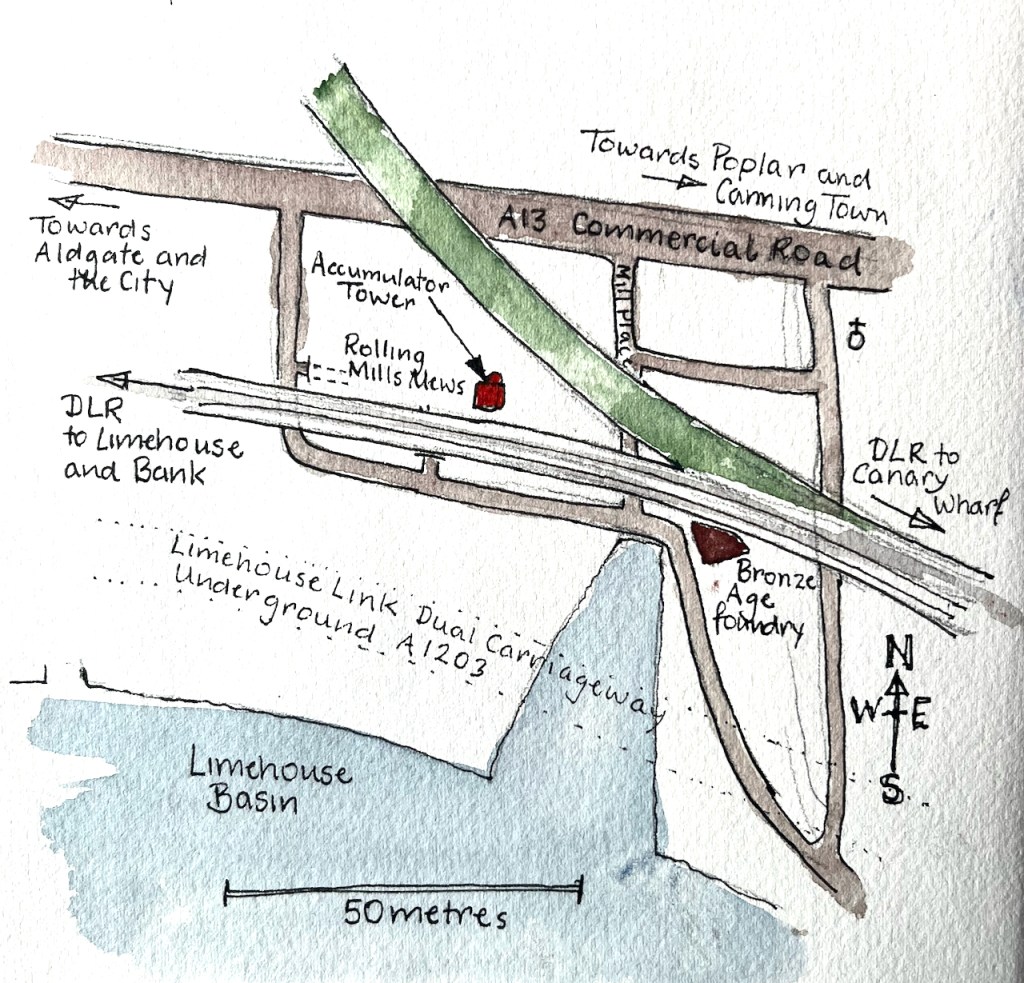

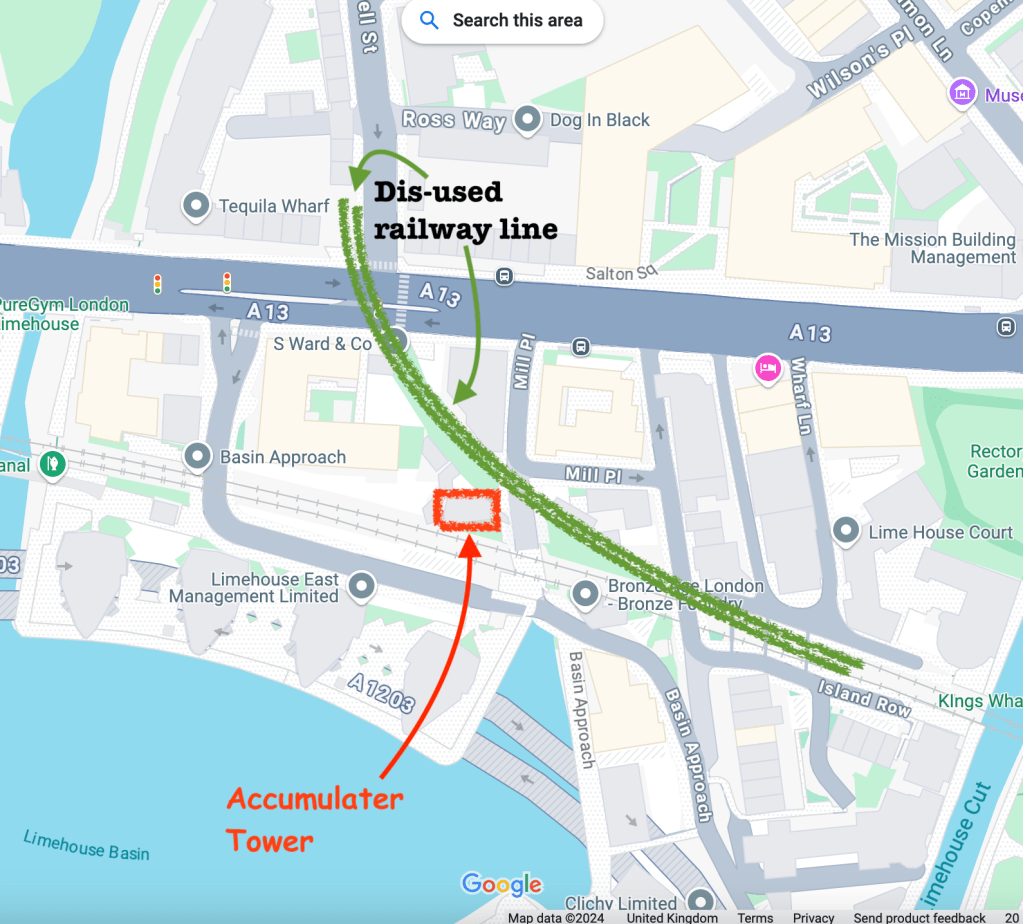

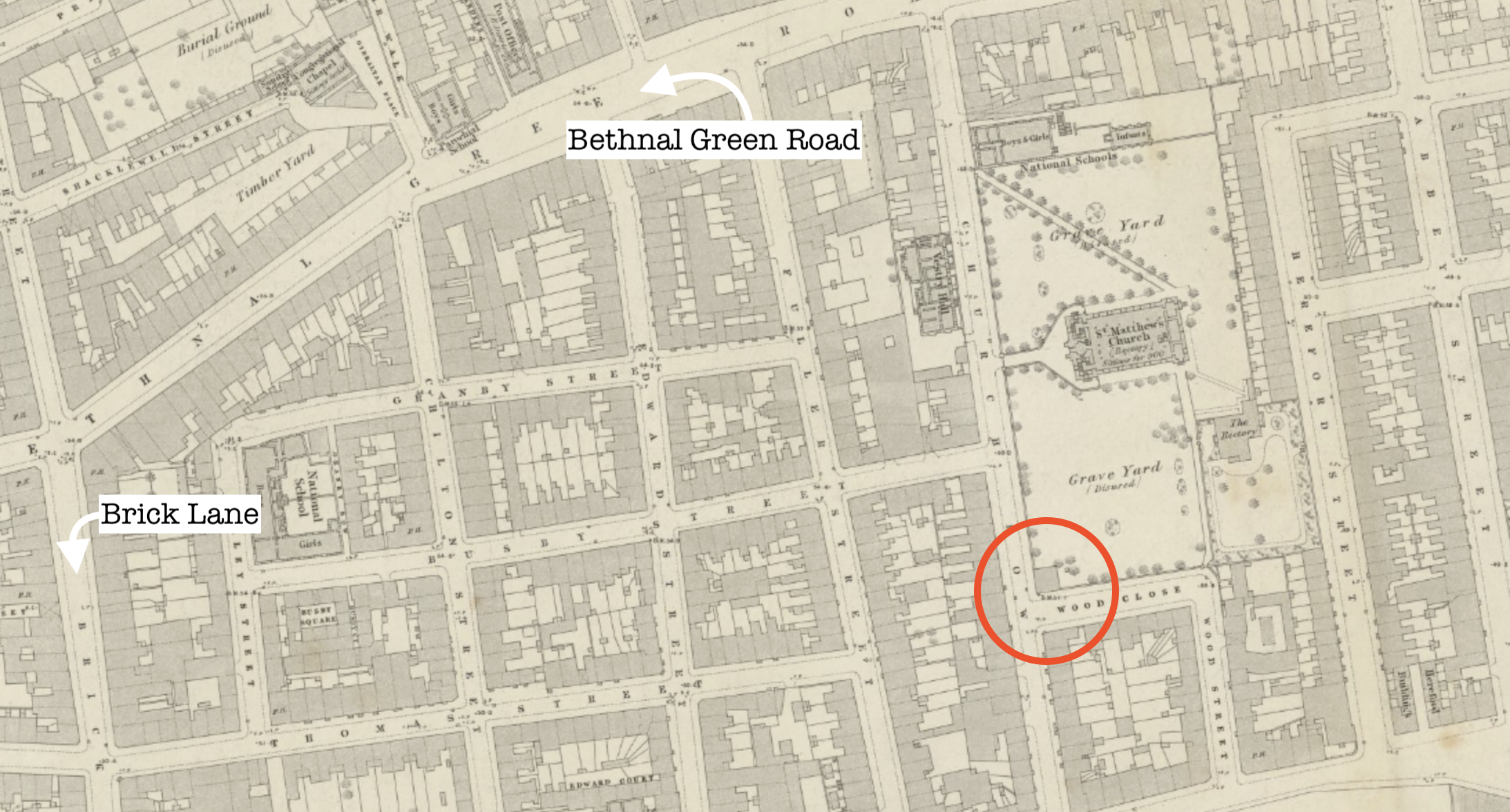

This link shows a 1872 map. Here’s an extract. Click the map to go to the National Library of Scotland map which is very detailed. The street is called “Wood Close” on this map. You can see the “Grave Yard (disused)”. The Watch House, circled in red below, is in the corner of the graveyard, which makes sense.

As you see in my sketch, there are now a prodigious number of bollards in front of the house. I counted ten of them, standing like an amused crowd next to the “7′-0” sign . While I was standing there sketching, I saw why. The idea is to restrict the width of St Matthew’s Row so that vehicles have to slow down or stop, and cars can’t sneak round the edges. I watched agog as huge limousines edged between the bollards.

This Watch House, and the nearby Parish Hall are owned by St Matthews Church:

The Church also own the Watch House on Wood Close, which is currently let out to private tenants, and the Parish Hall on Hereford Street, currently let out to State51.

https://www.st-matthews.org.uk/hire-our-spaces/

It’s a house on a corner, with an active life and a history. I was glad to make its acquaintance.