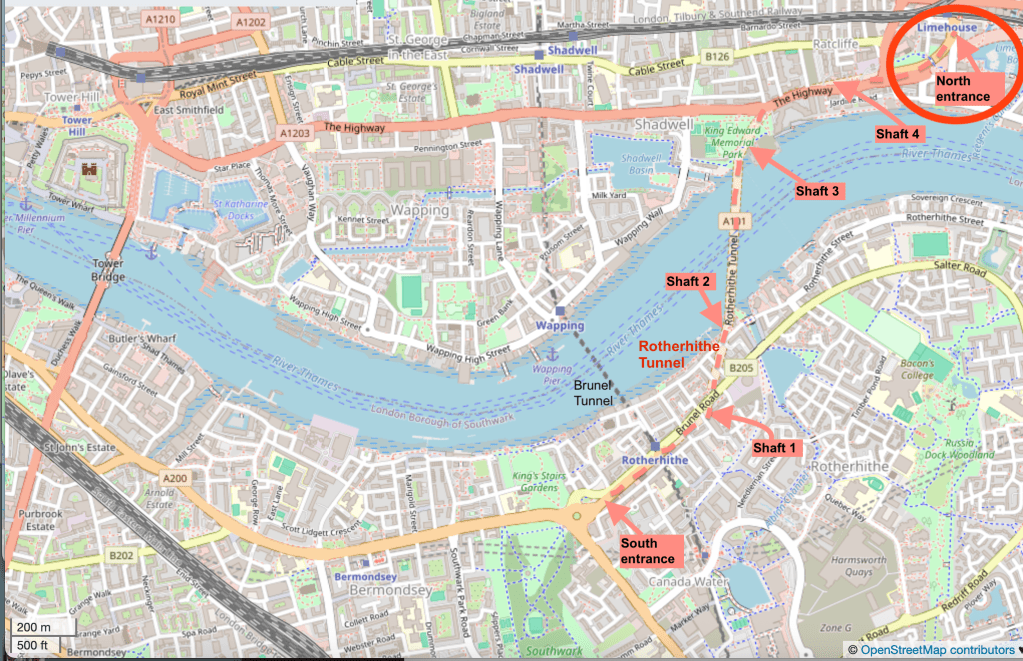

The Rotherhithe Tunnel carries road traffic in both directions between Limehouse on the north of the River Thames, and Rotherhithe on the south side. It was constructed between 1904 and 1908, for horses and carts. The designer was Sir Maurice Fitzmaurice.

The tunnel links Limehouse on the north of the river to Rotherhithe on the south. Built originally for horse-drawn carriages and pedestrians, the tunnel now carries far more traffic than it was designed for, which requires careful day to day management by TfL to ensure safety.

Transport for London press release 20181

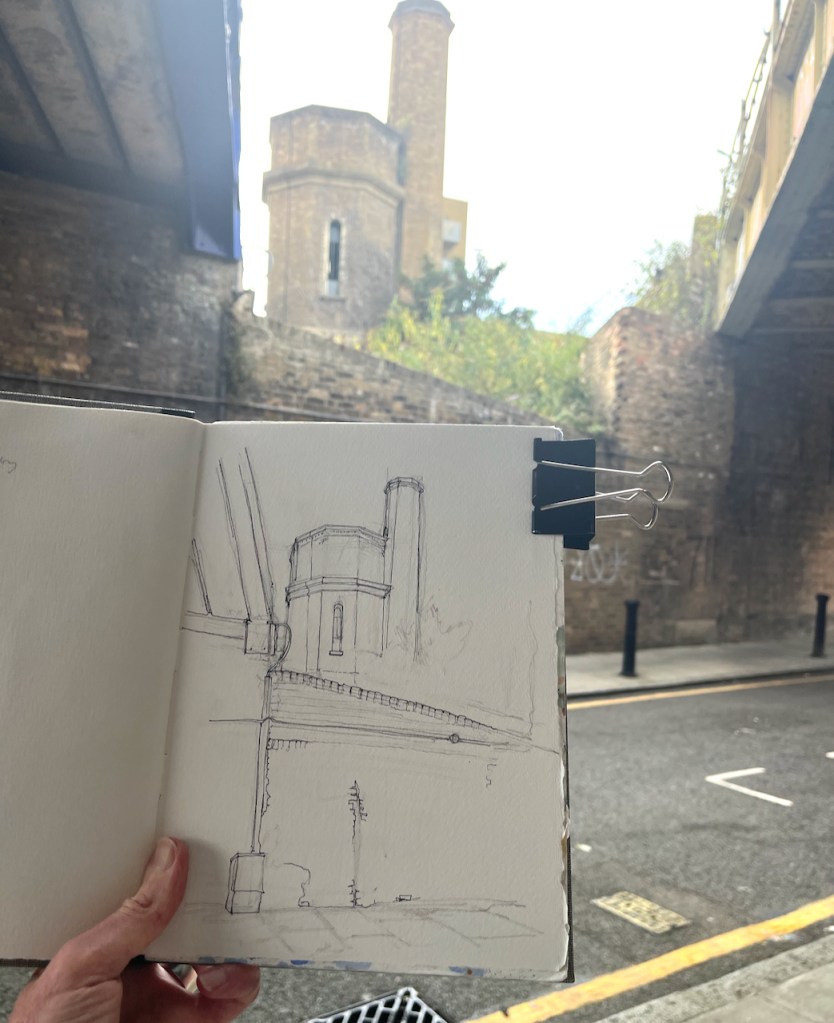

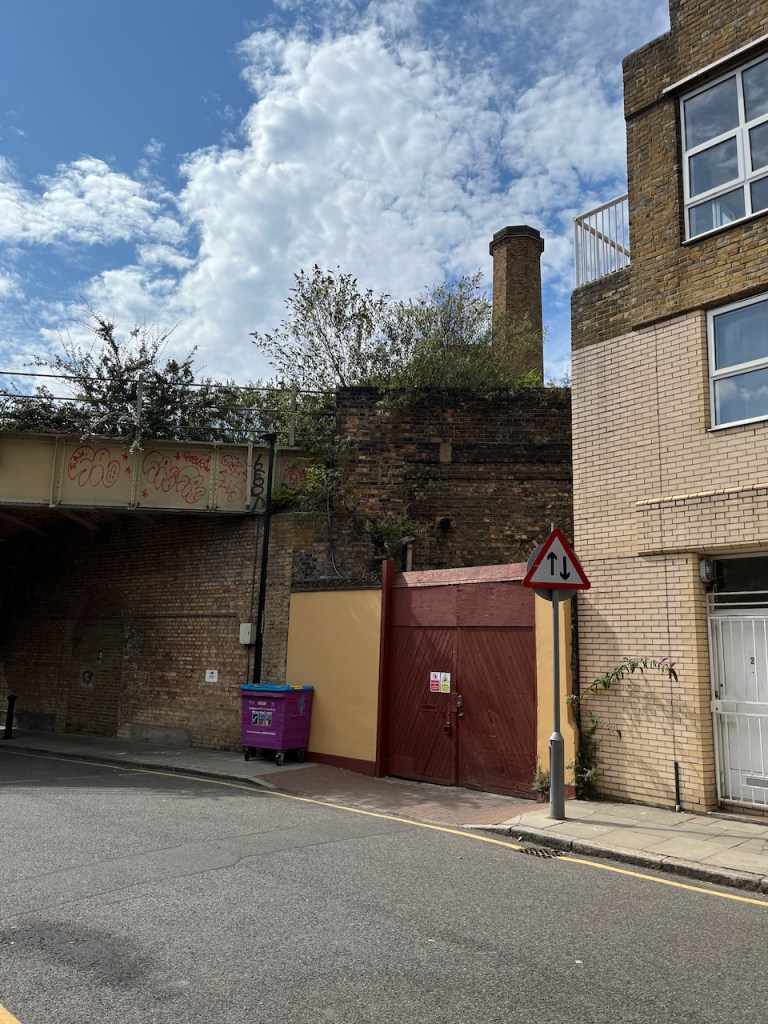

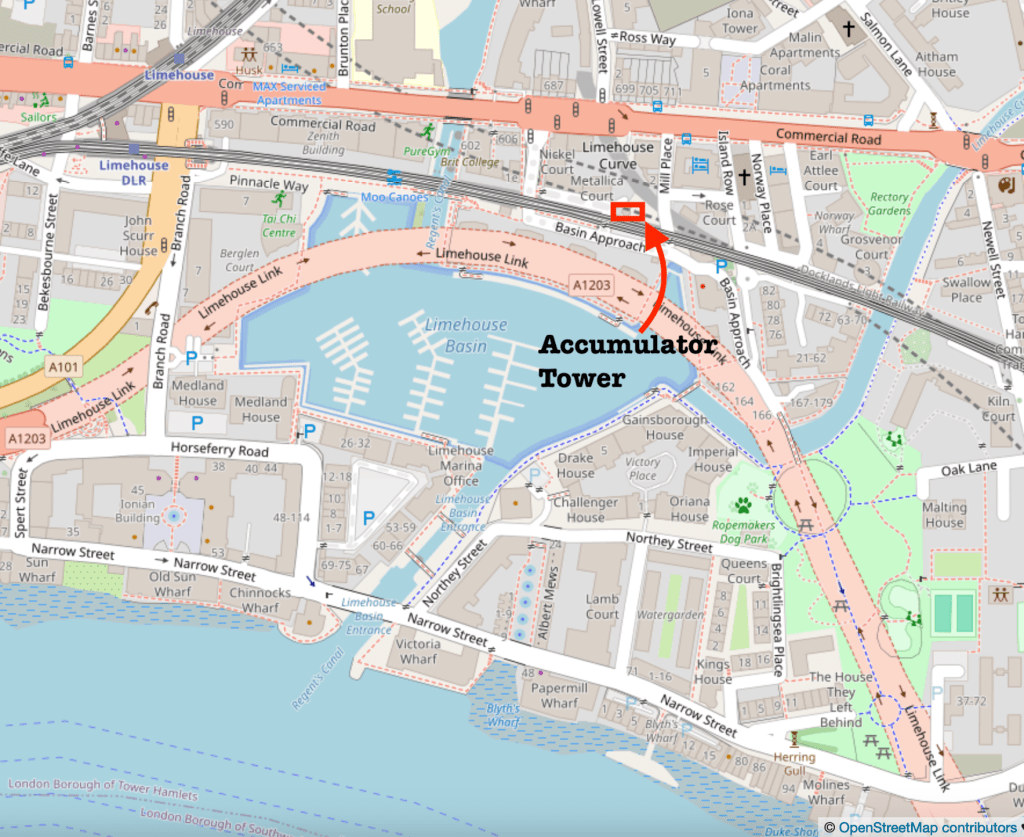

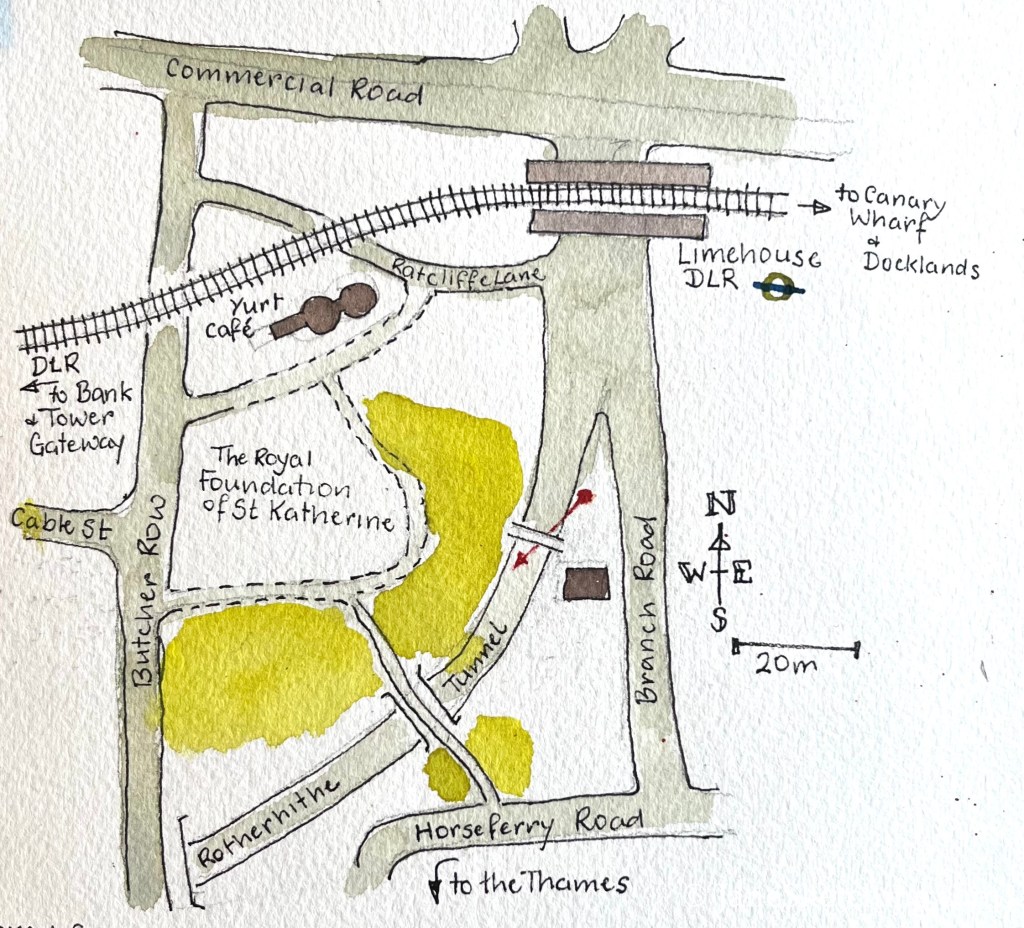

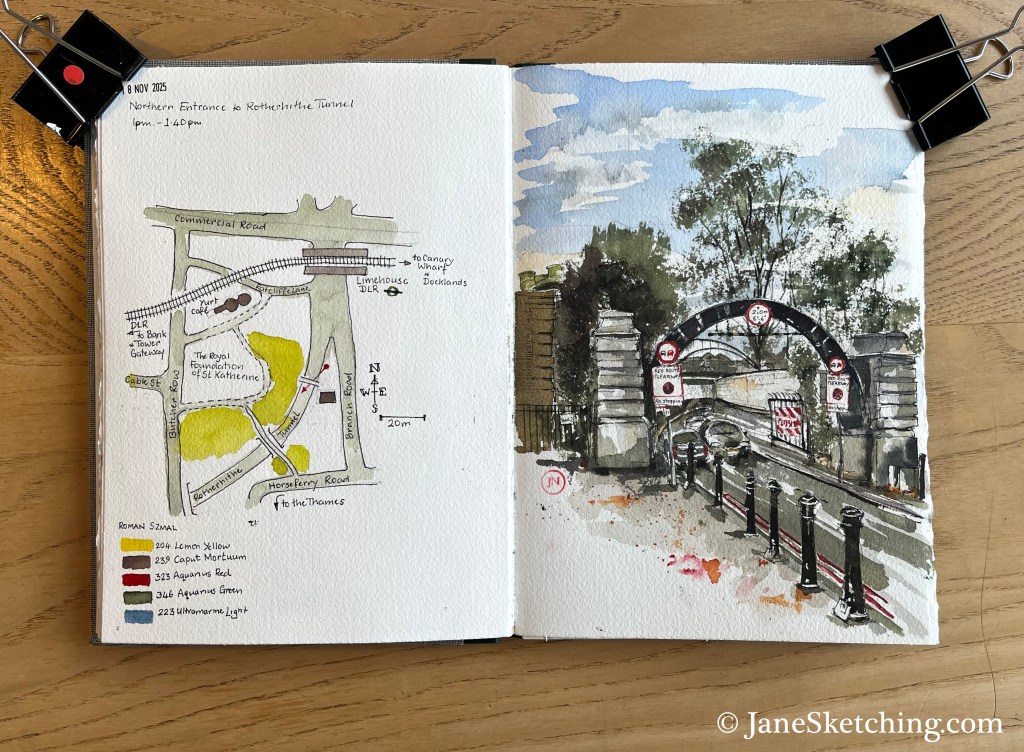

Here is the North Entrance of the Rotherhithe tunnel, near to Limehouse DLR Station in the east of London.

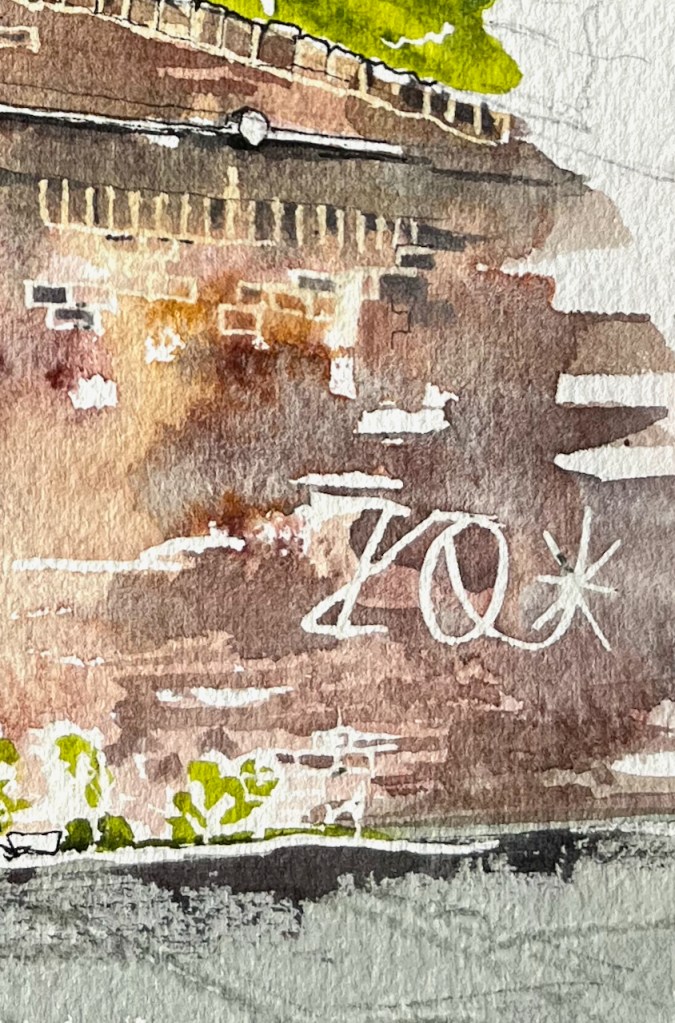

The arch in the picture is made of steel. A notice on one of the columns explains that this arch is part of the equipment used to construct the tunnel.

You can see the steel structure in the photo below. The tunnel is narrow. As you see in my sketch, there are just two lanes. The tunnel is heavily polluted from exhaust fumes. Even so, as I sketched, some people cycled into the entrance. Cycling in the tunnel must be very unpleasant and scary. I feared for them.

Because of the limited space in the tunnel, there are size restrictions on traffic, including a height restriction. To indicate the safe height, there are long vertical tubes over the approach road, as shown in the photos below. These photos were taken looking back from near the tunnel entrance, towards Limehouse DLR Station, which you can see in the background.

While I was sketching, I heard the banging sound as an overheight van struck the metal tubes. This happened three times during the 45 minutes I was there. Each time, the vehicle carried on past me into the tunnel.

On the road island where I stood to sketch, there are two red telephone boxes. Amazingly, one of them still had the phone inside.

Despite the bright company of the phone boxes, it wasn’t a great place to stand. I could smell the pollution from the tunnel and its approach roads and I didn’t think it was doing me any good. Also it was cold. So having made my pen sketch, I went off to cross the Thames in search of the south entrance.

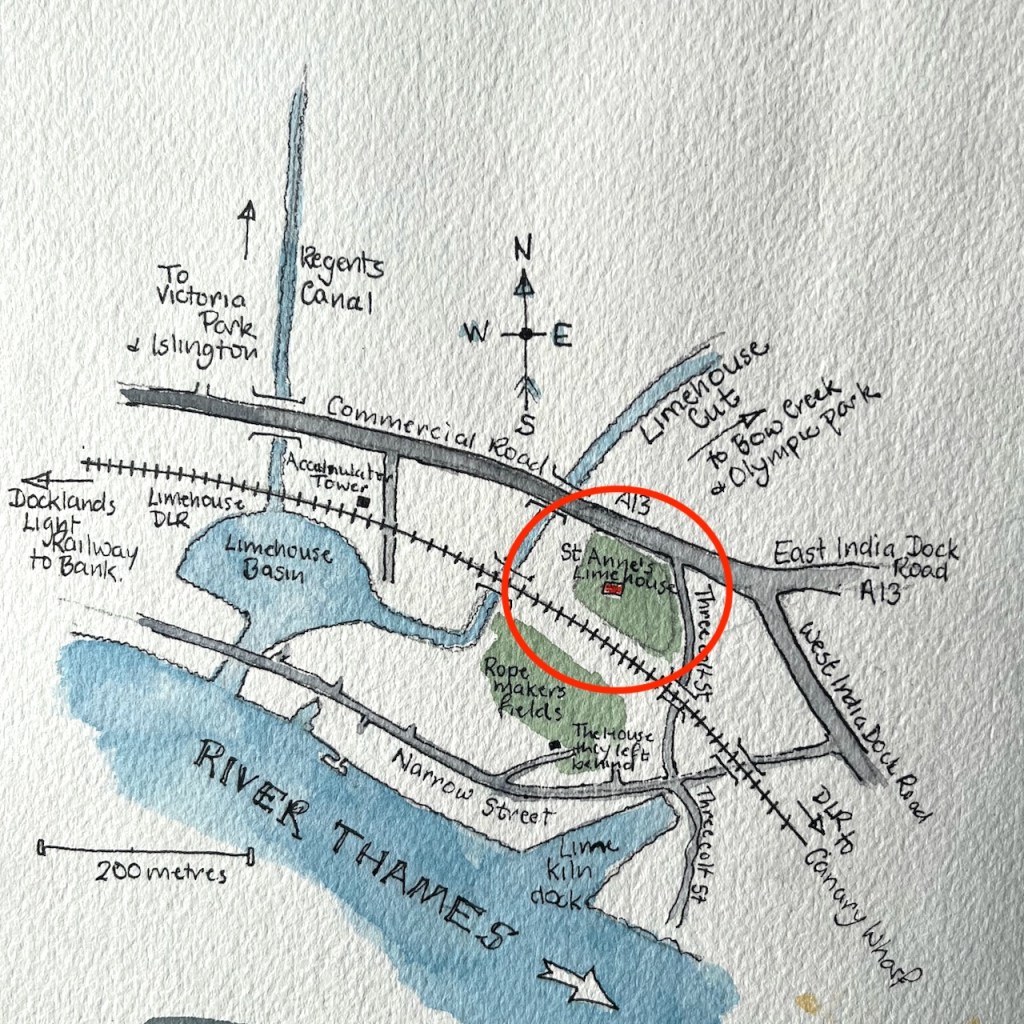

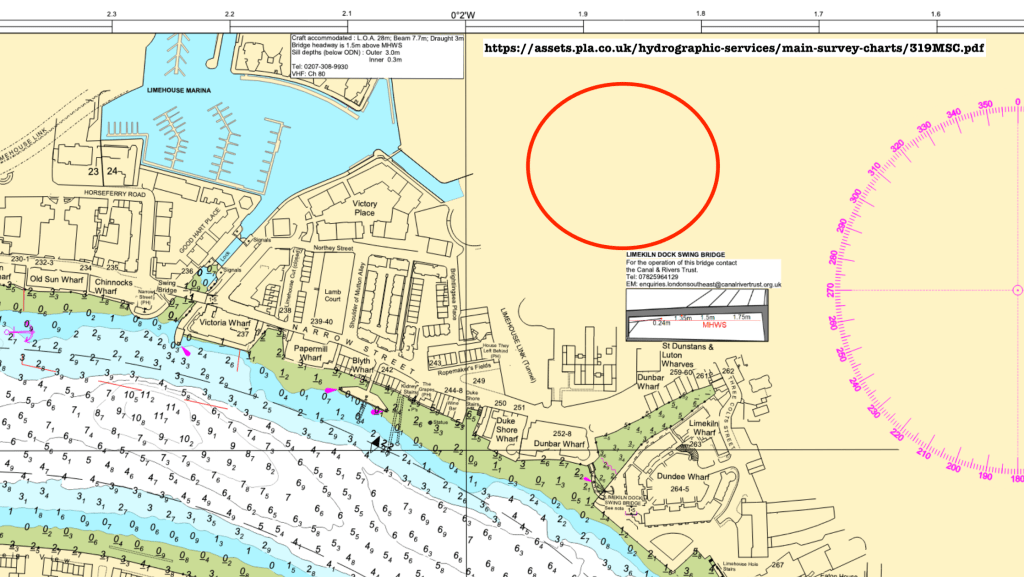

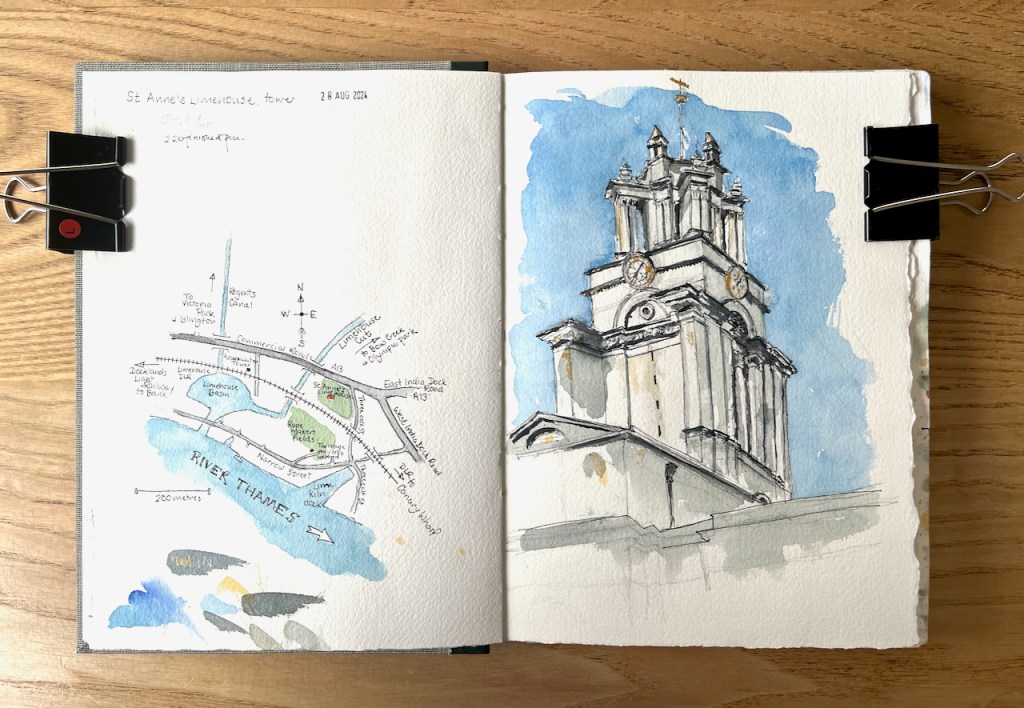

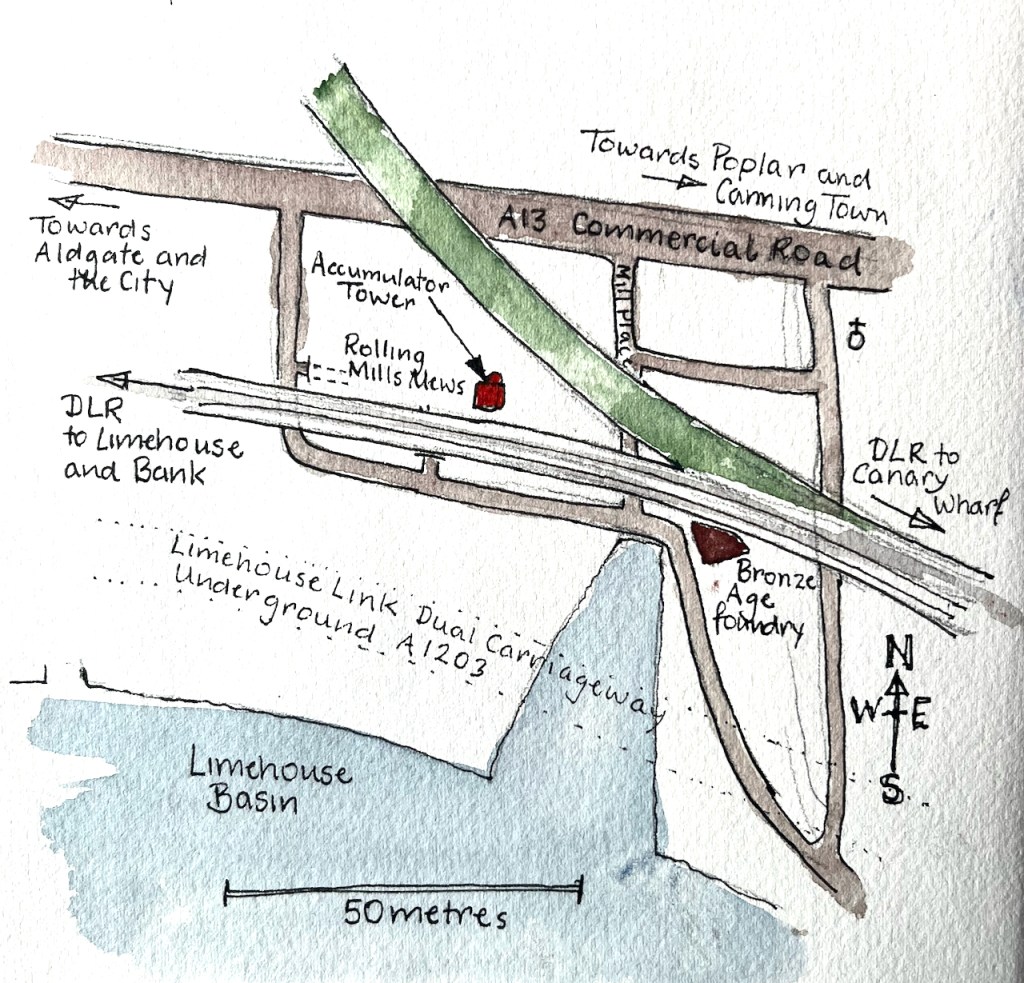

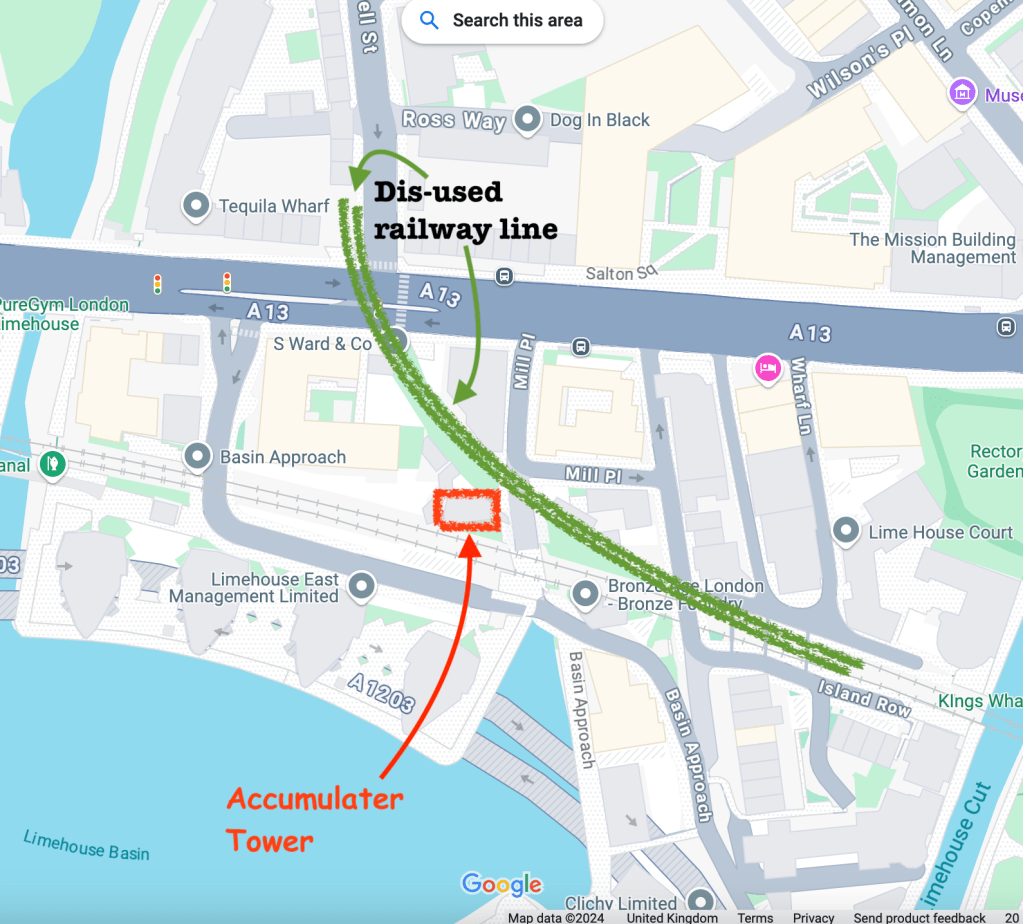

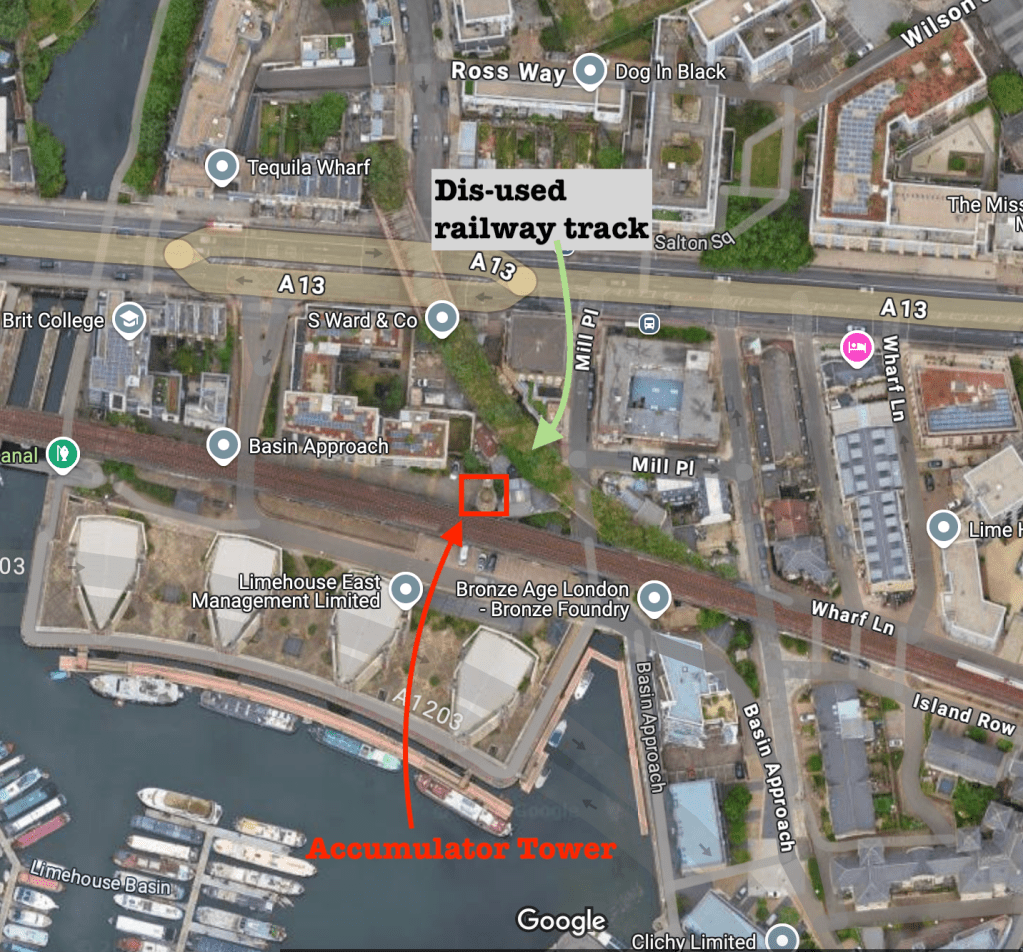

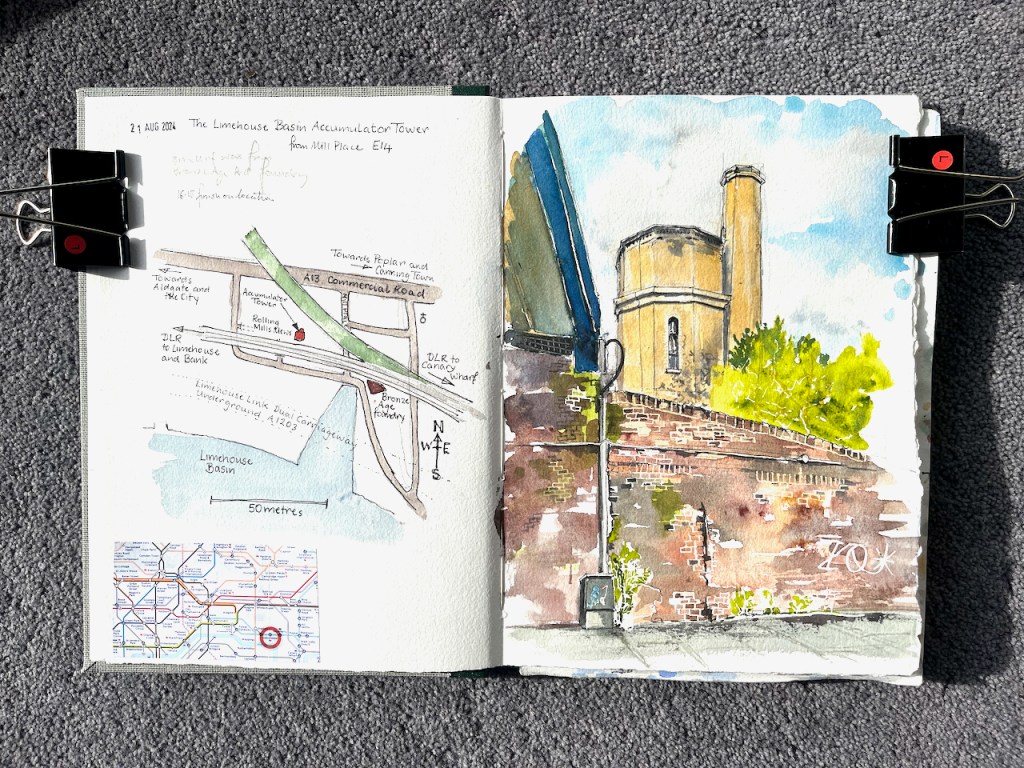

Here are maps, click to enlarge them.

I used Roman Szmal watercolours for this picture. It appears in an article on the Jackson Art Supplies website, reviewing these colours. Here are the colours I used:

- Transport For London Press release 12 June 2018 contains data about the number of vehicles using the tunnel: https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2018/june/rotherhithe-tunnel-celebrates-110-years-of-transporting-people-across-the-thames ↩︎ ↩︎