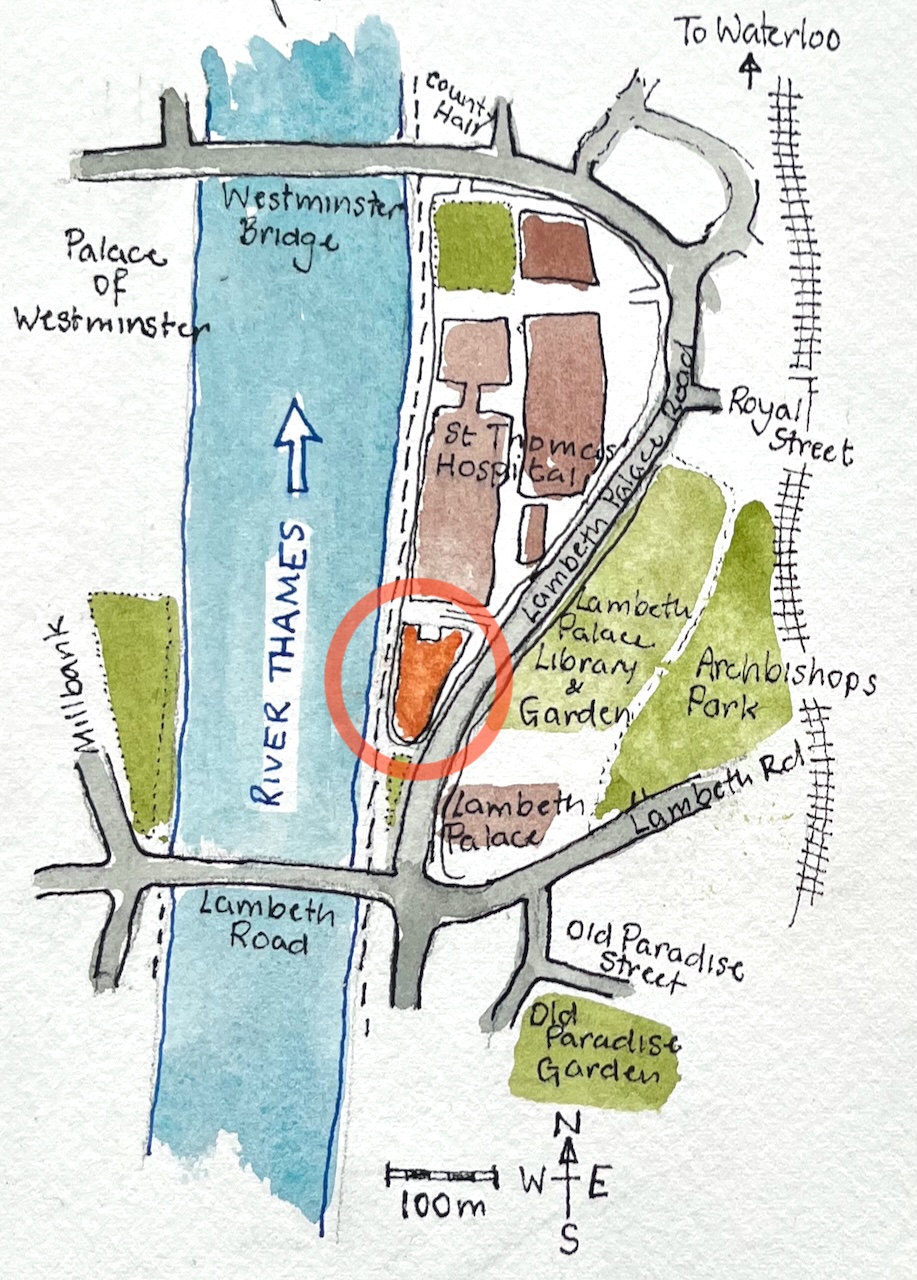

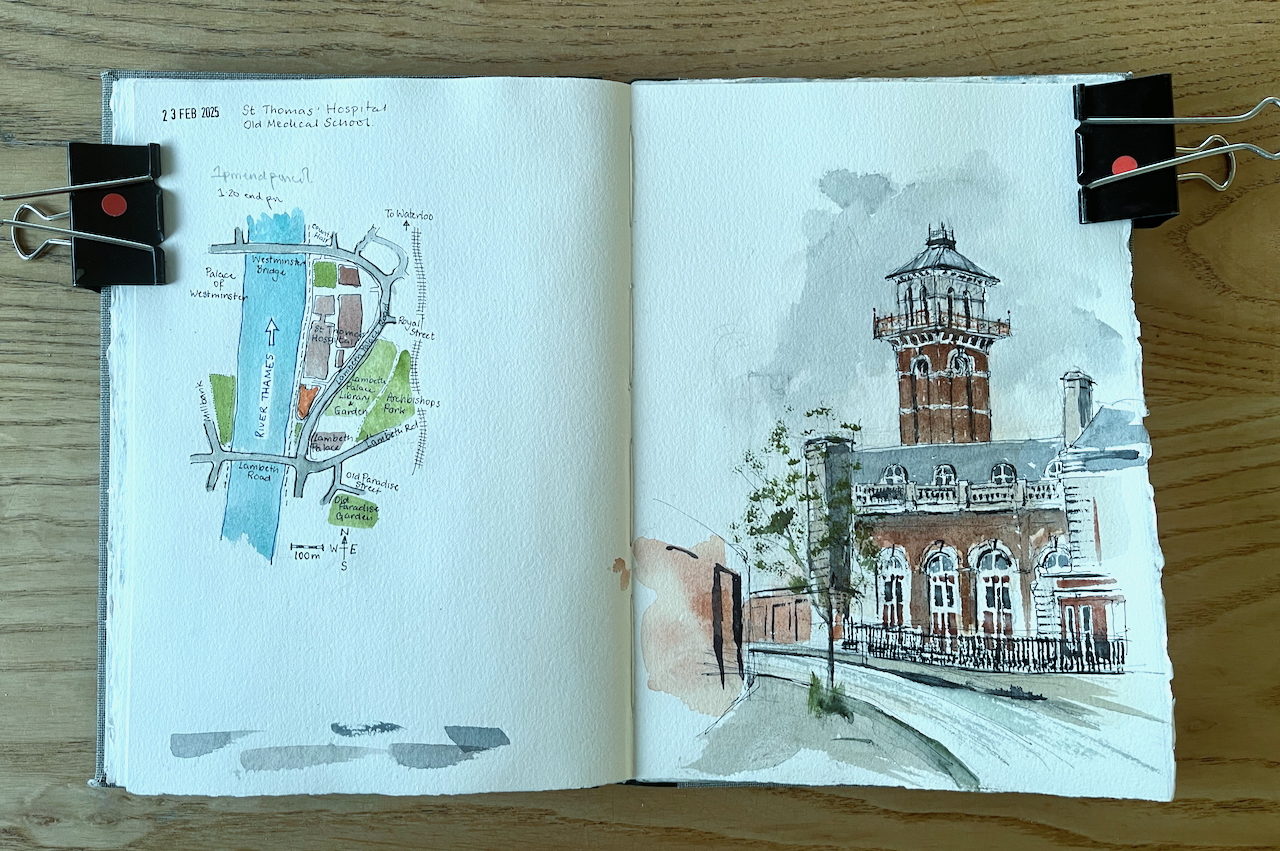

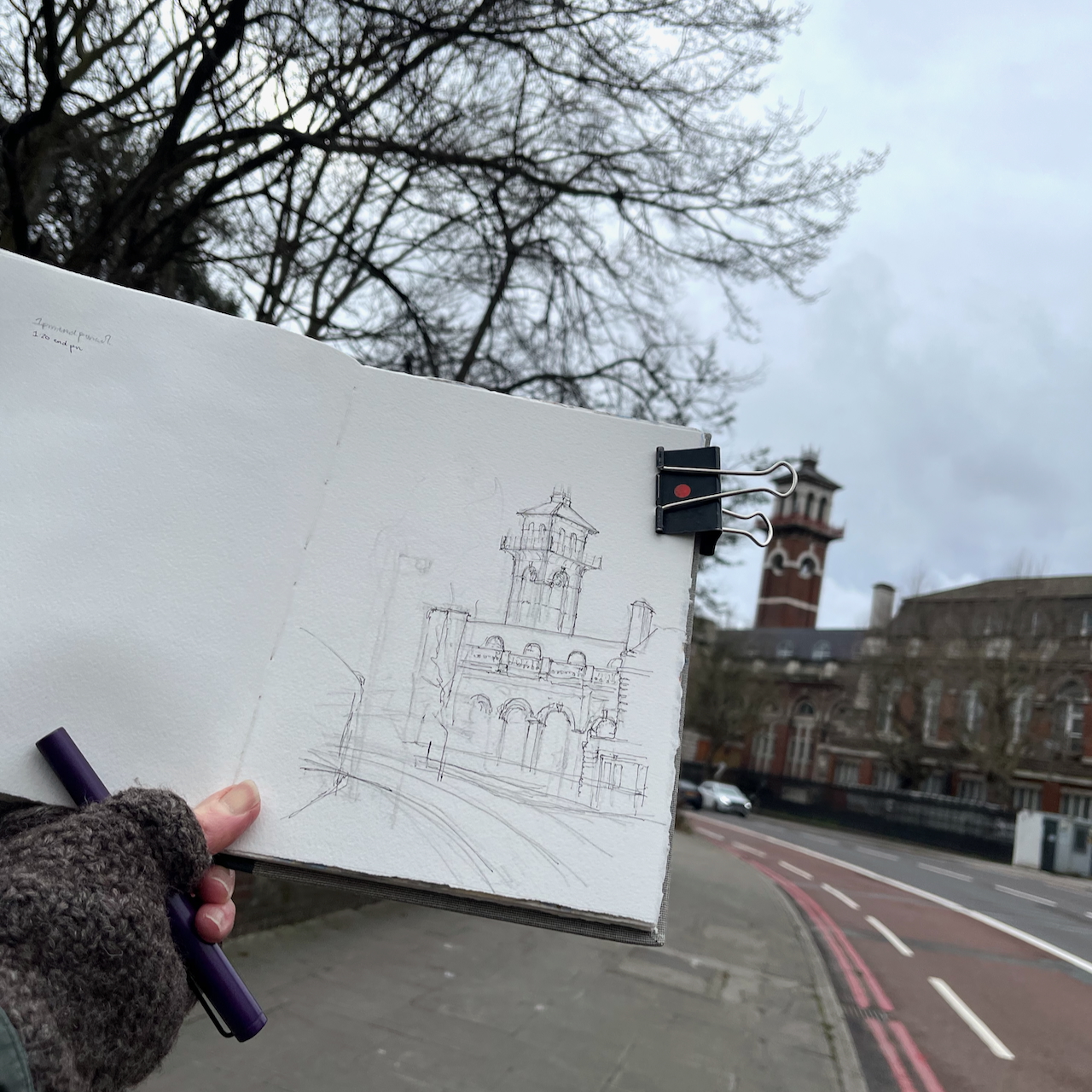

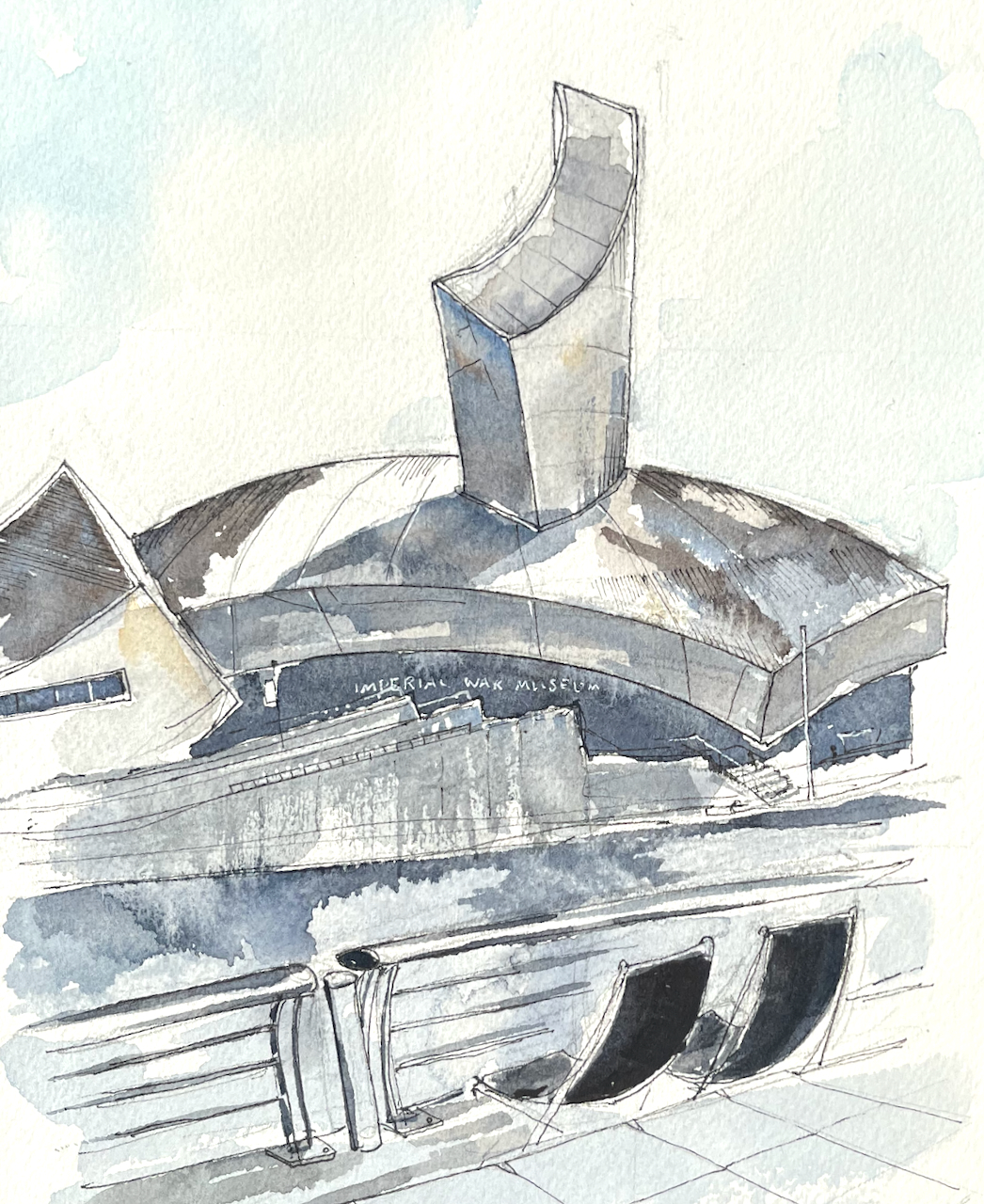

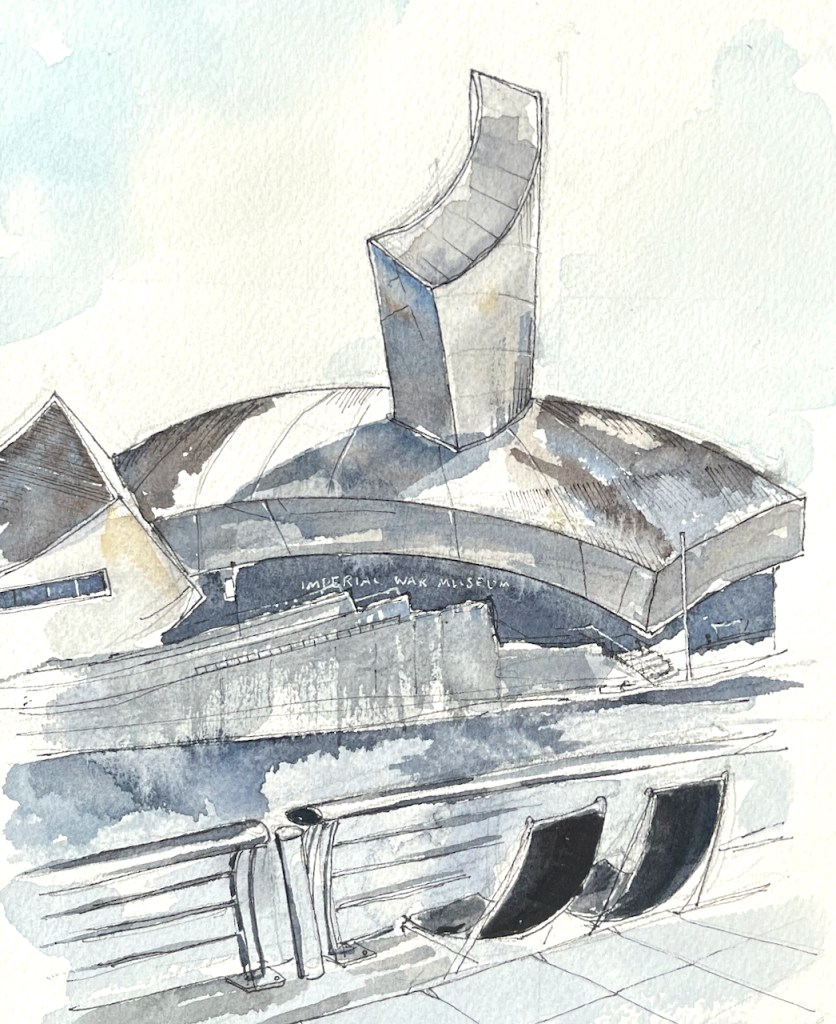

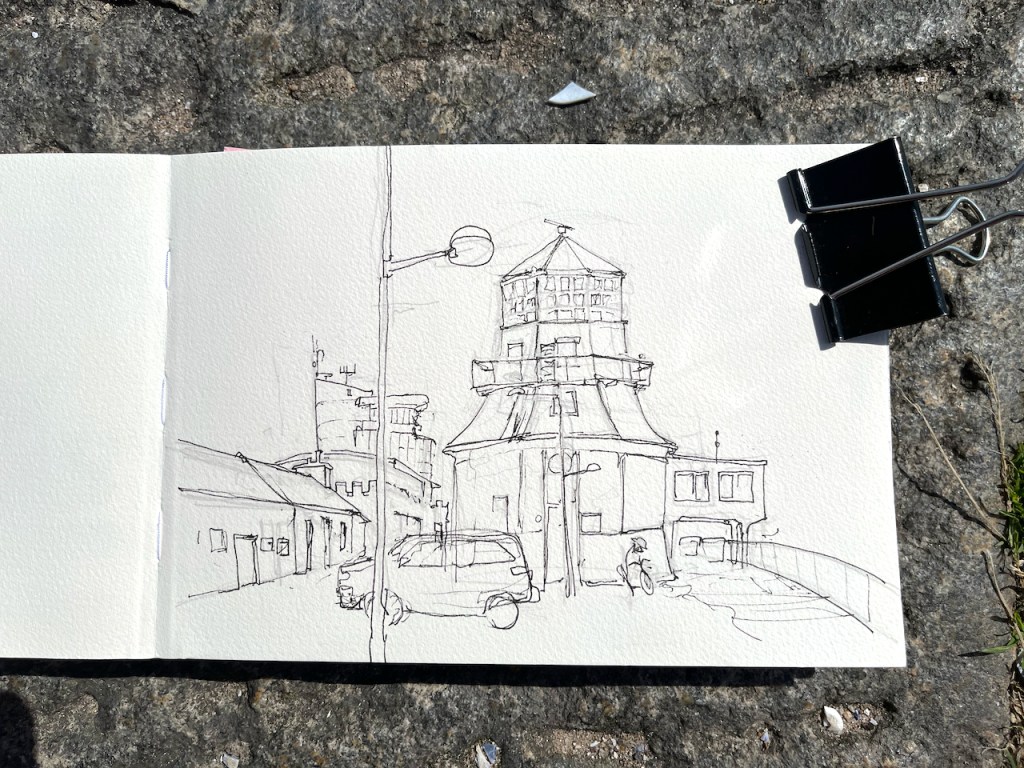

There is a splendid tower south of St Thomas’ Hospital on the South bank of the River Thames. Here it is, sketched from the Lambeth Palace Road.

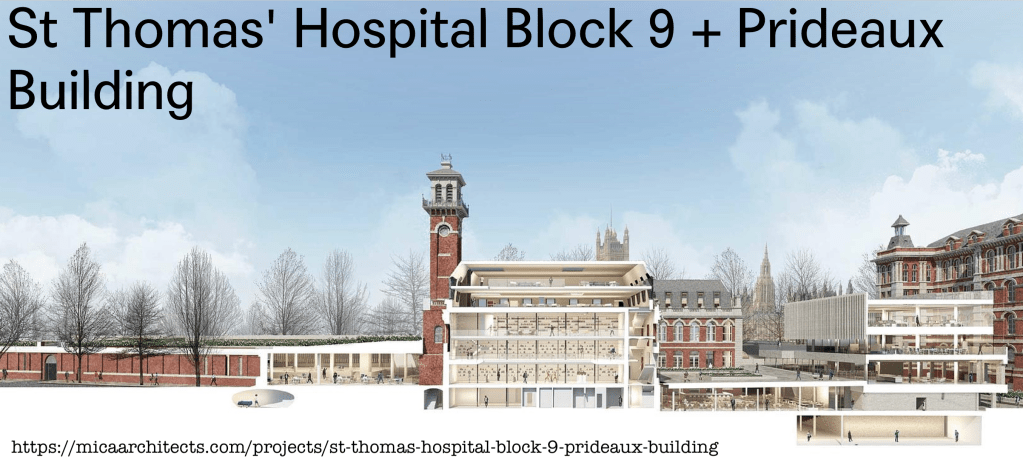

This tower, and the buildings below it, are right next to the Thames, opposite the Houses of Parliament. It is a splendid position.

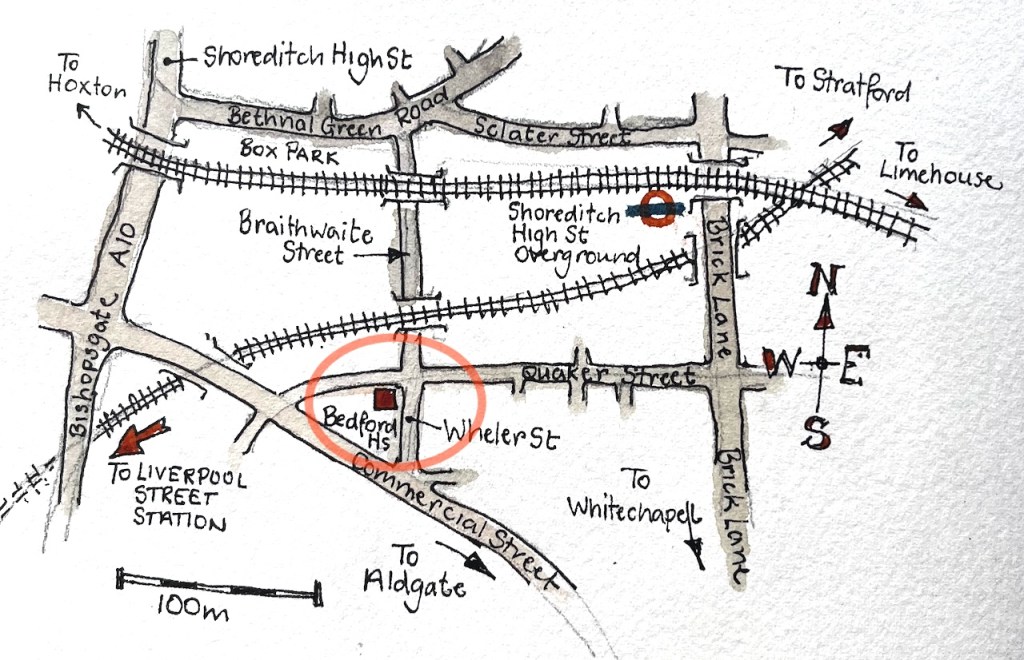

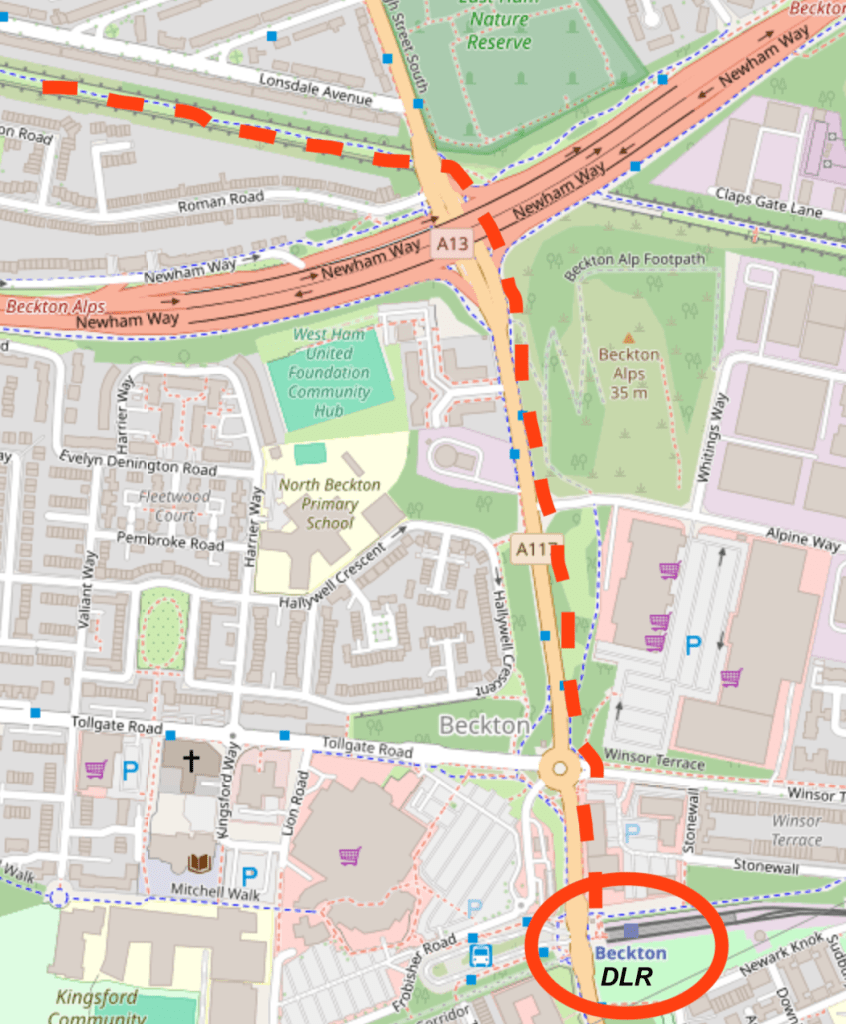

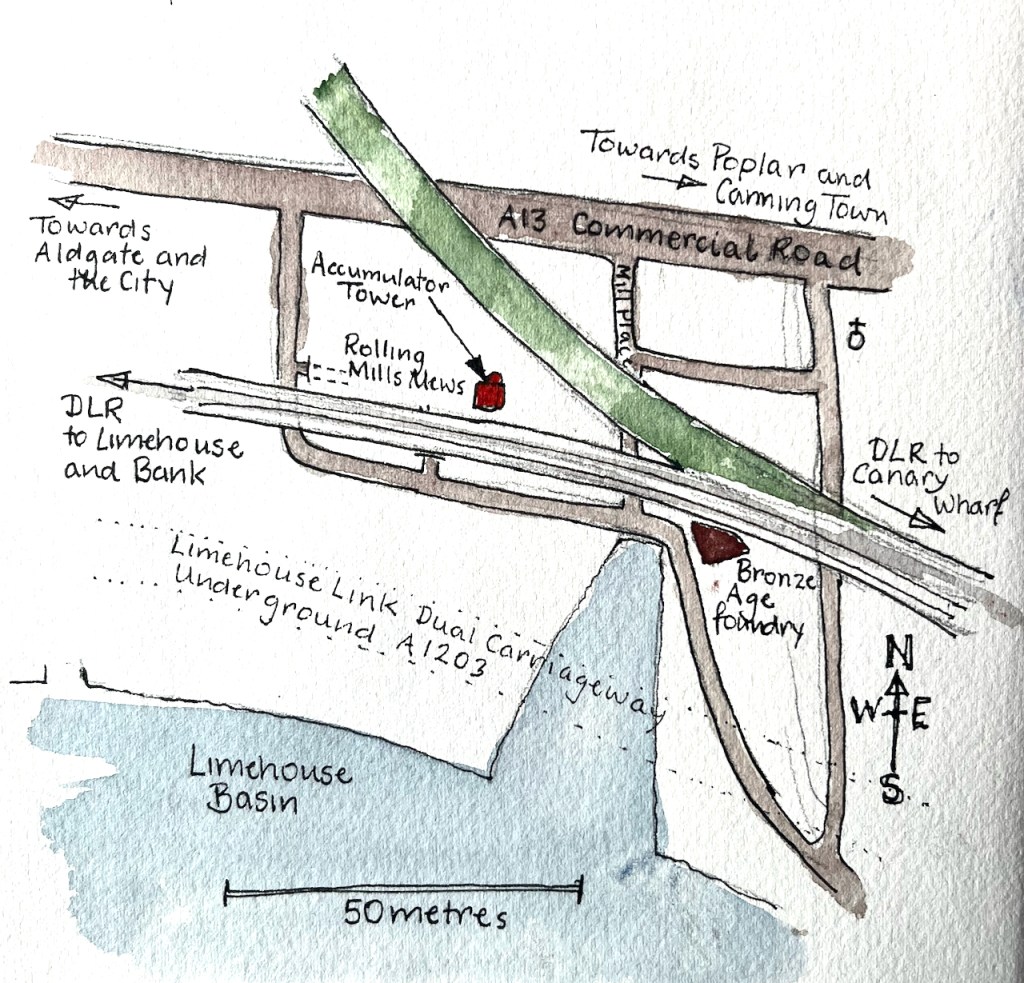

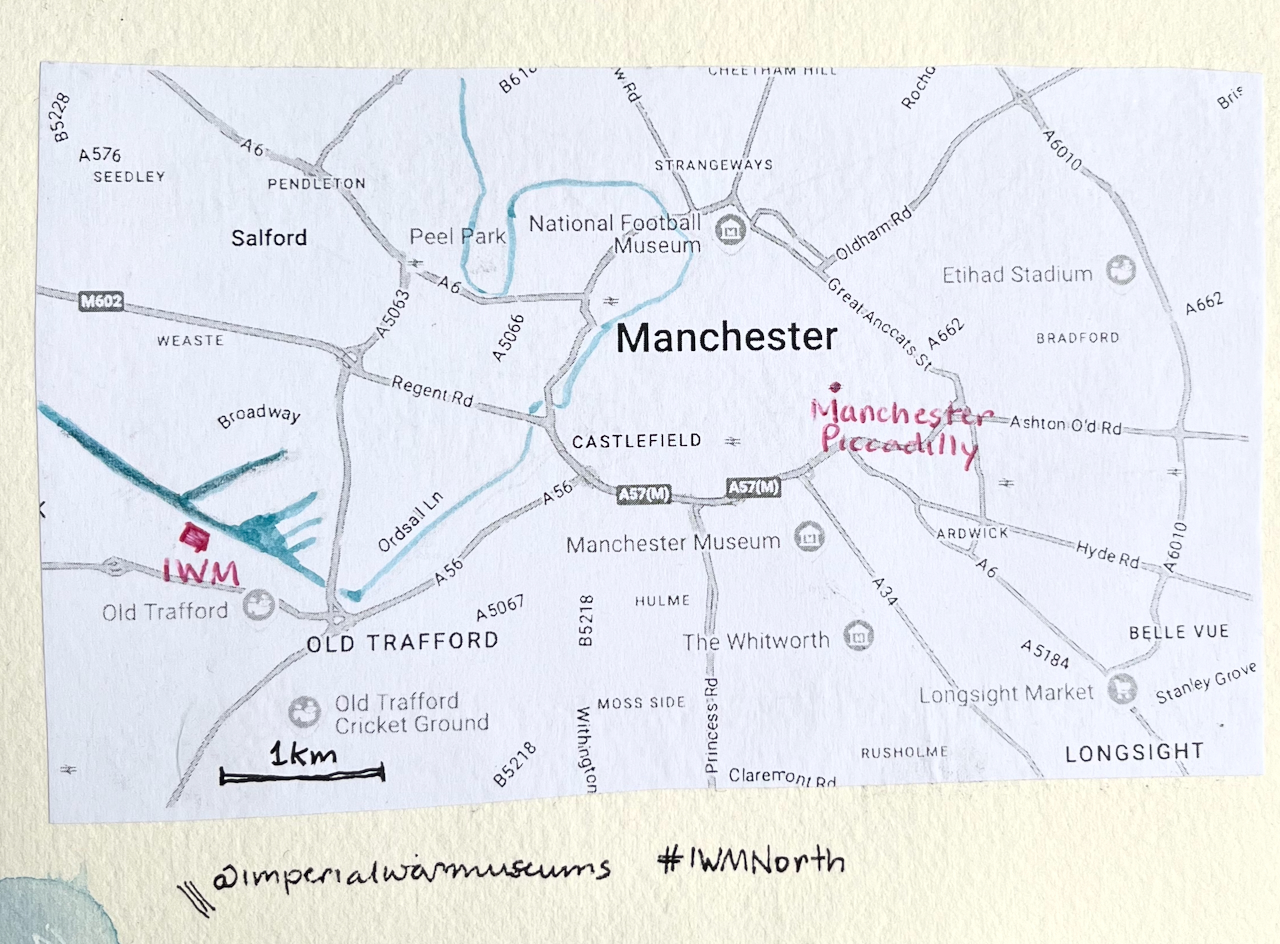

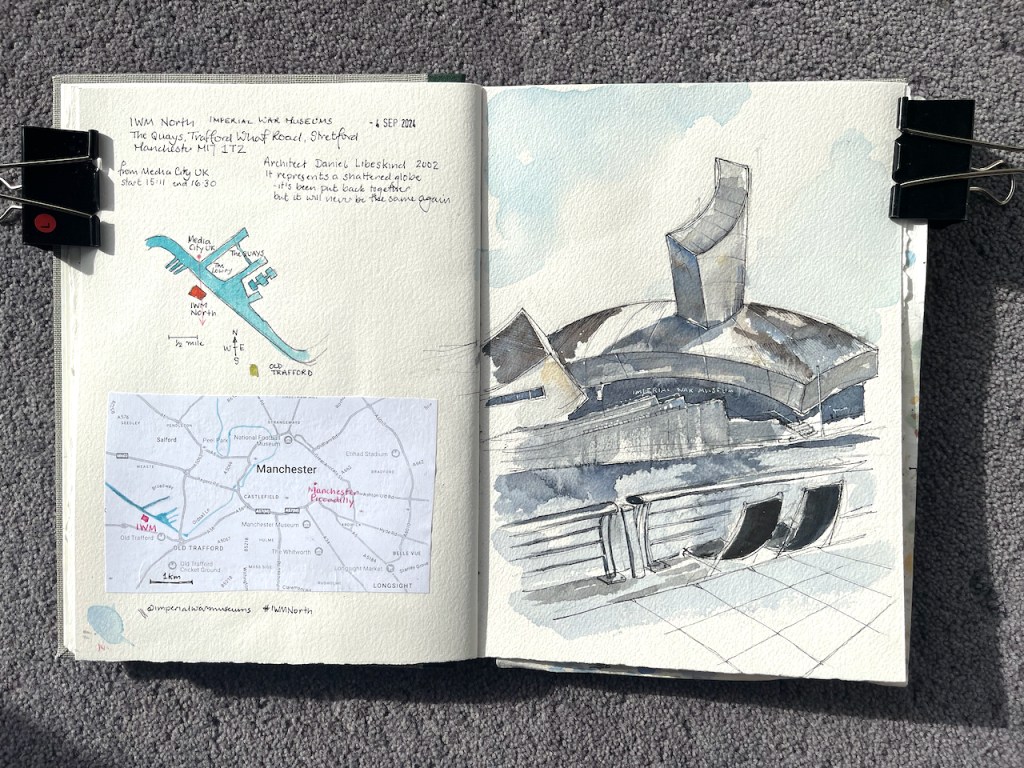

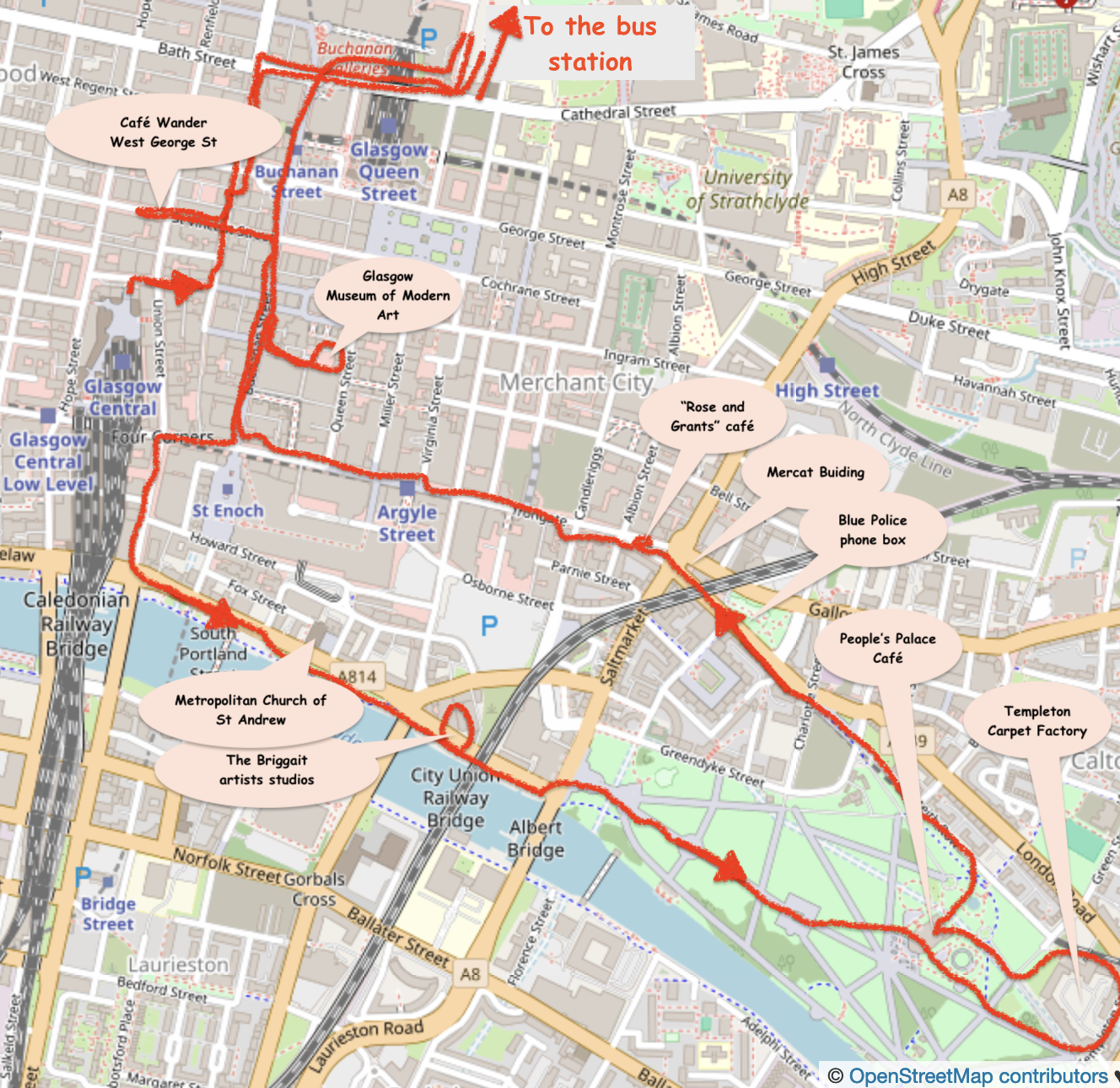

Map (c) Openstreetmap contributors. Click to enlarge.

Given this prominent central location, I was astonished to discover that these buildings are derelict.

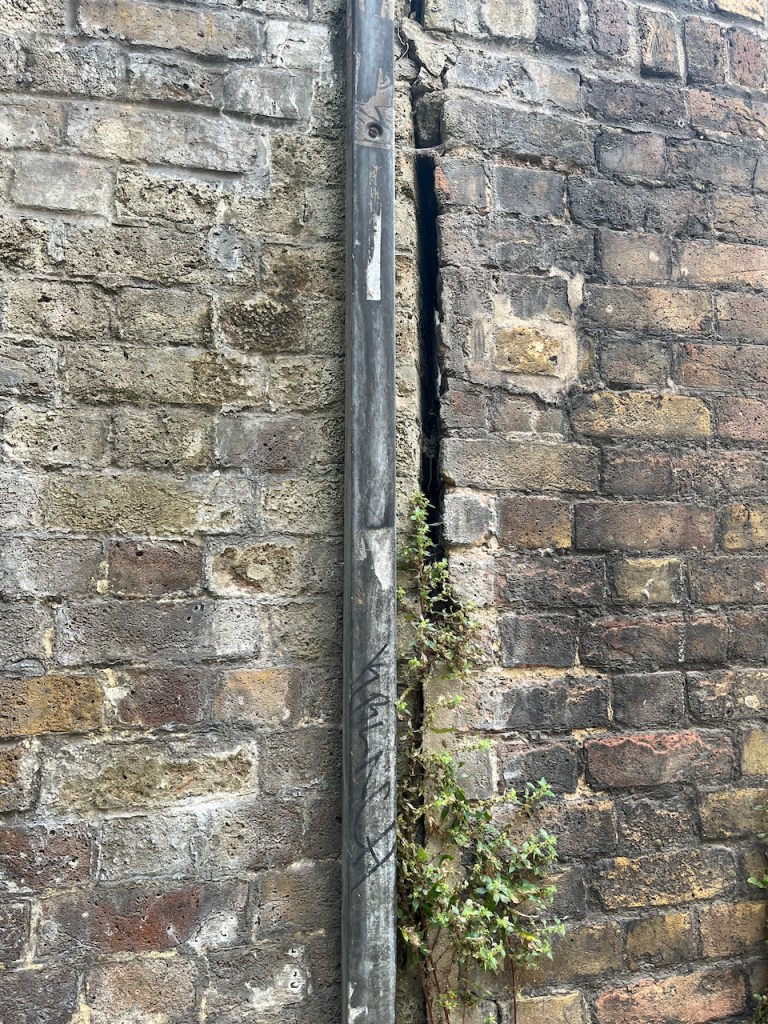

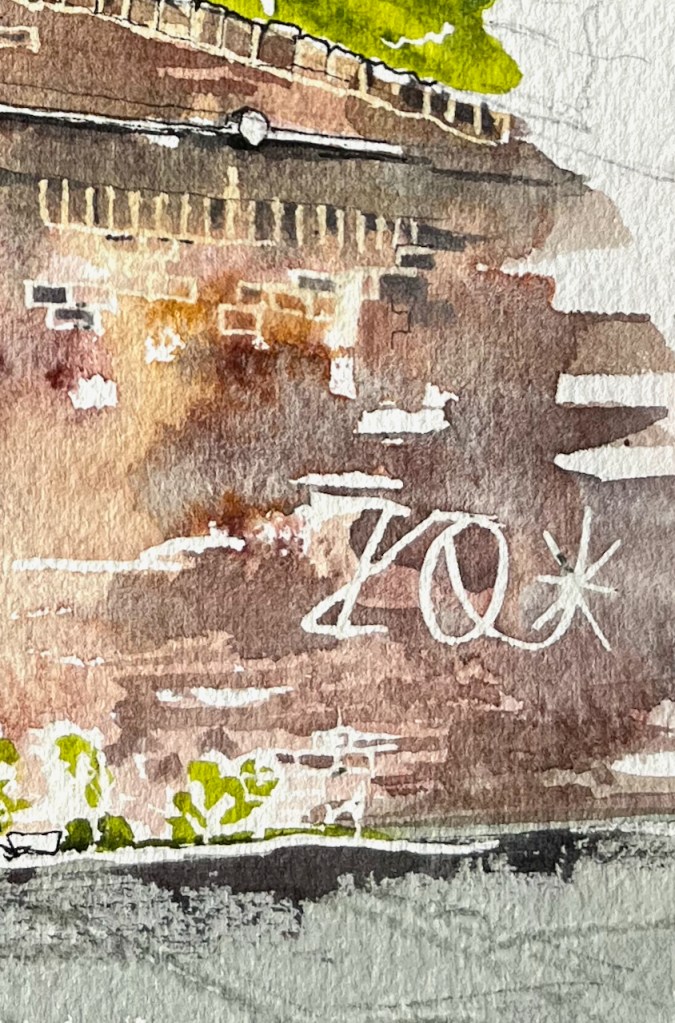

If you look through the railings which are in my drawing, this is what you see:

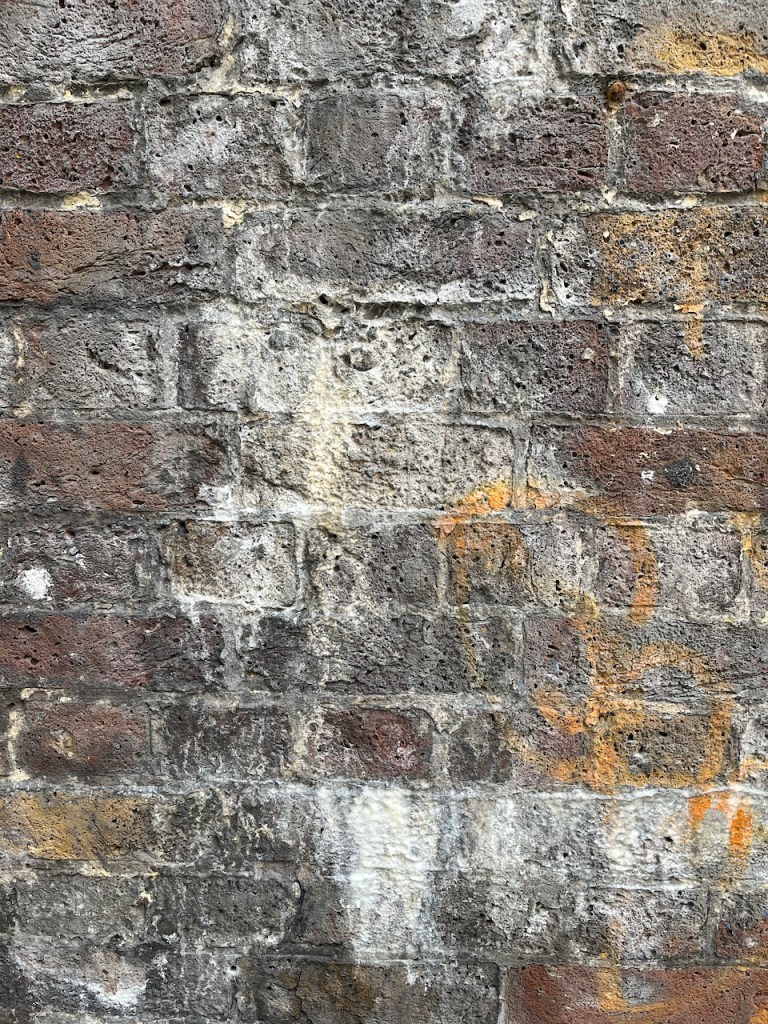

Urban explorers have posted pictures of the sadly decayed interior. For example on this link and this link and this link. Some have ascended the tower and posted pictures taken from up there. Their photographs show an abandoned lecture theatre, peeling plaster, elegant fireplaces covered in dust and mould, laboratory samples lying about gathering dust, molecule trees in a tangled heap, test tubes and old notes.

As well as the grand buildings, there are low-level houses within the site.

So what’s going on?

This part of St Thomas’ hospital was a medical school and library since the hospital was built here in around 1870. This part of the site was abandoned 20 years ago, as medical schools moved and merged. Then, it seems, nothing happened for 10 years, as the lecture theatres, laboratories and corridors gradually decayed.

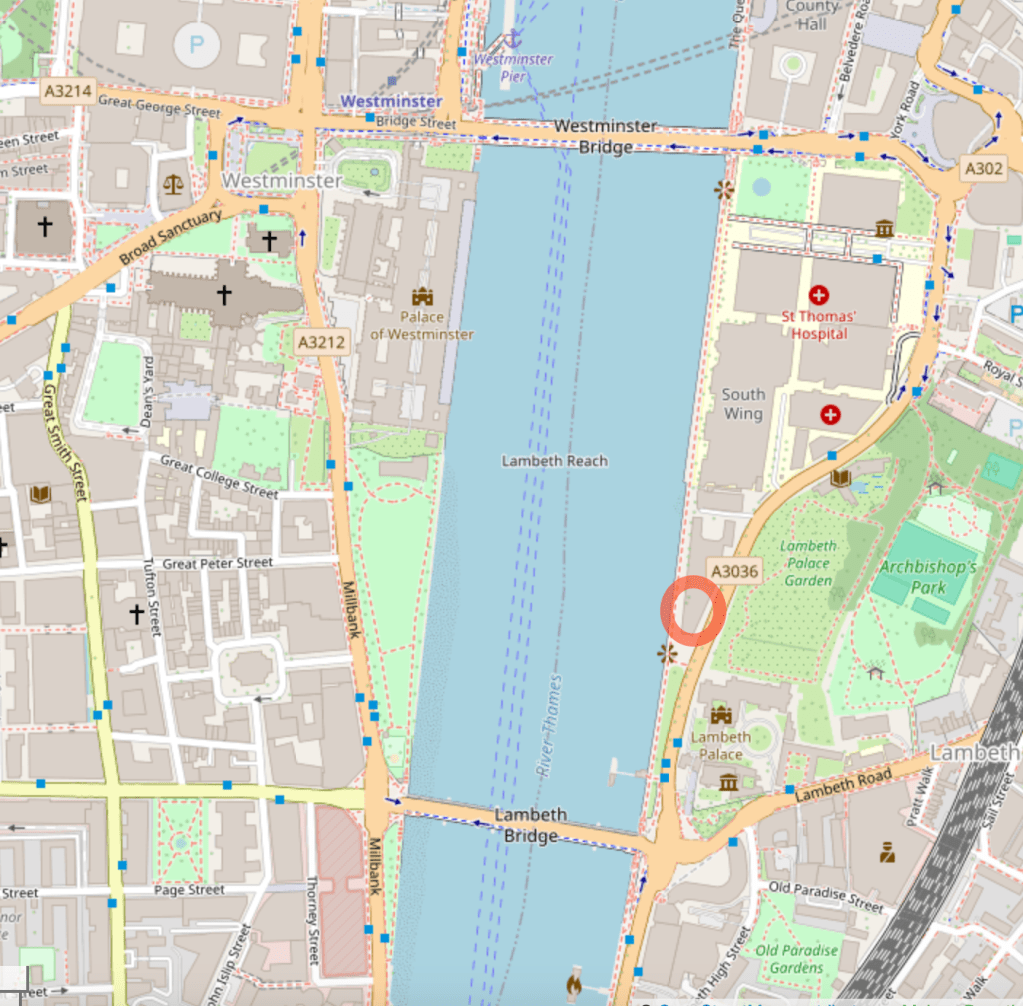

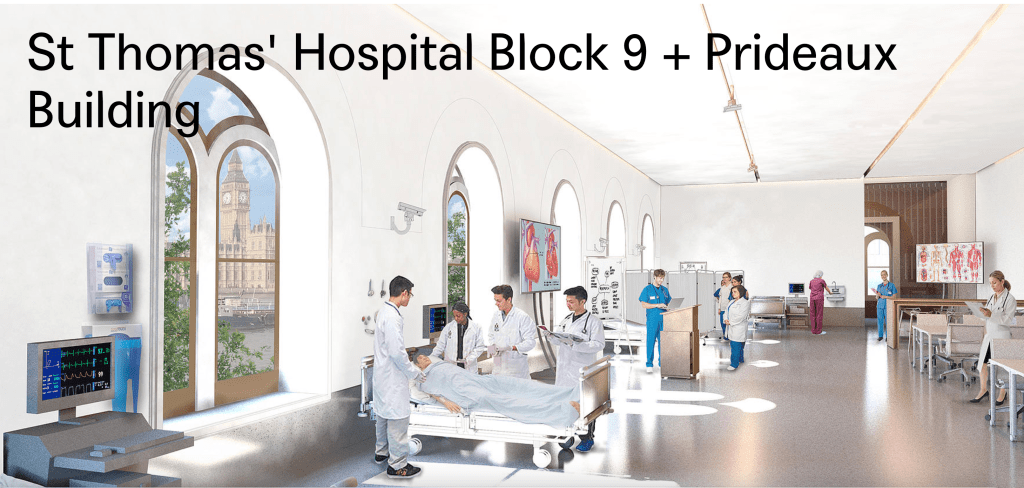

In 2015, there was a plan. The website for MICA architects shows a proposal for a new medical school on this site. This proposal is dated “2015-ongoing”. Click the image below to see their drawings of radical new buildings, and future medical students engaged in lectures and conversations, with spectacular views of the Houses of Parliament through the huge windows.

Lambeth Council granted planning permission in 2016, reference 16/02387/FUL. That was nearly ten years ago. Still the site remains derelict.

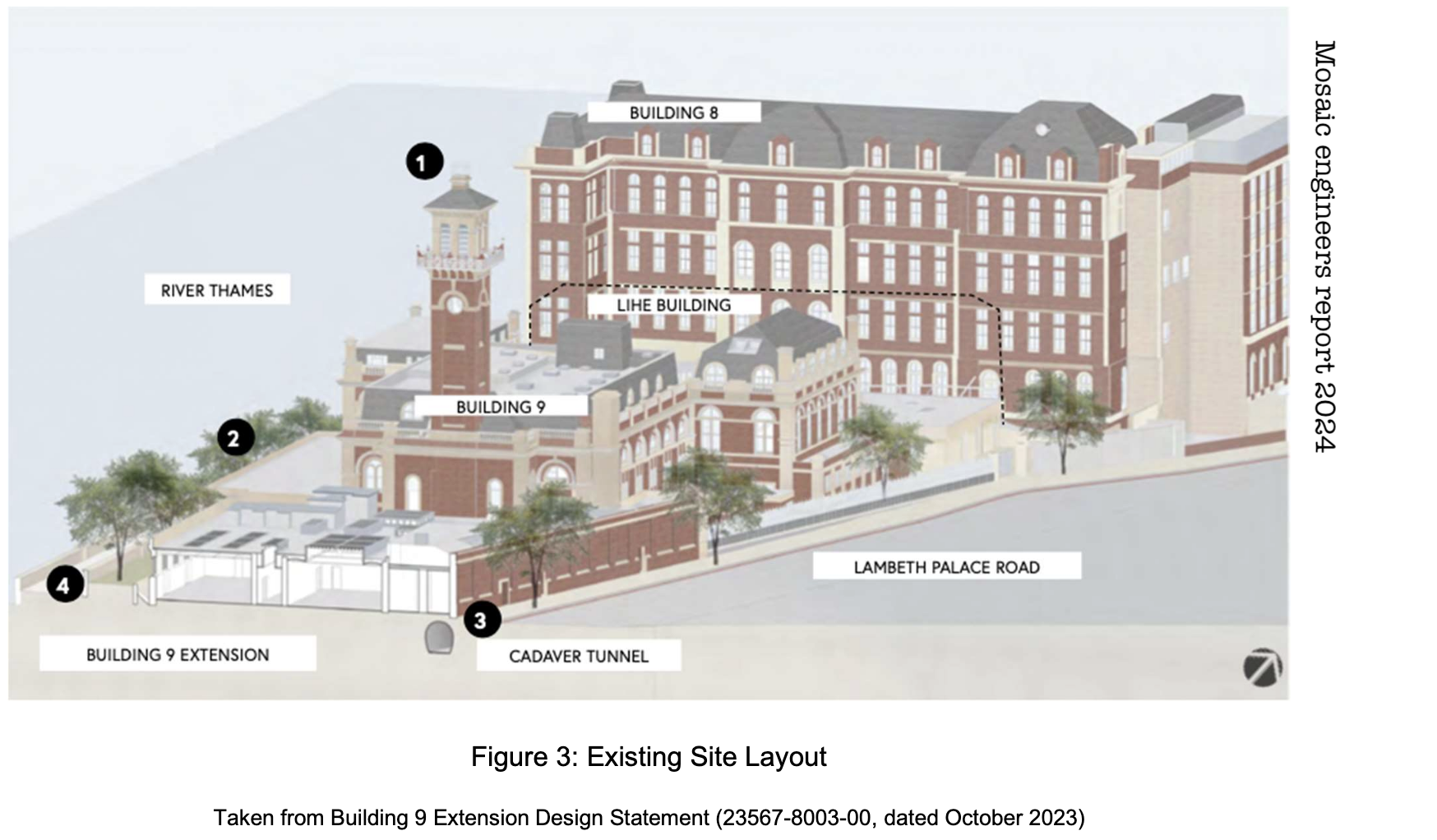

However, now it seems that progress is happening. On the Lambeth Council planning site, there is an impressive in-depth survey of the site by Mosaic Civil engineers, dated July 2024. They look at the Geology, Soil Chemistry, Hydrogeology, Hydrology, Flood Risk, Unexploded Ordnance, Ground Stability, and Invasive Weed, to name but a few. Hydrogeology seems to be answering the question: are there any aquifers or wells here? (answer: no). Hydrology is answering the question: how does the water flow around here, and will any sewage or nasty chemicals wash into the site? (answer: well, there is a Thames Water “storm sewage overflow” pipe into the Thames just upstream from here….). This report also contains photos, and a useful history of the site (Note 1).

St. Thomas´ Hospital was constructed in its current location in 1871 following the

Mosaic engineers report page 6, history of the site

construction of the Albert Embankment (which required reclamation of land from the River Thames)and the demolition of old boatbuilding and barge house sites which dated back to the 1680s.” (page 6, history of the site)

The volume “London – South” of the Pevsner architectural guides, says that St Thomas’ was..

…built on the current site by Henry Currey 1868-71, one of the first civic hospitals in London to adopt the principle of “Nightingale” wards to allow maximum ventilation and dispersal of foul air.

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) was a pioneering nurse and reformer of the profession. She had a profound impact on the architecture of hospitals.

“The first principle of hospital construction is to divide the sick among separate pavilions,” she wrote in her 1863 ‘Notes on Hospitals’. Pavilions were large, rectangular, open-plan wards that made it easier for nurses to supervise all patients. These wards became known as Nightingale Wards.”

London Museum website

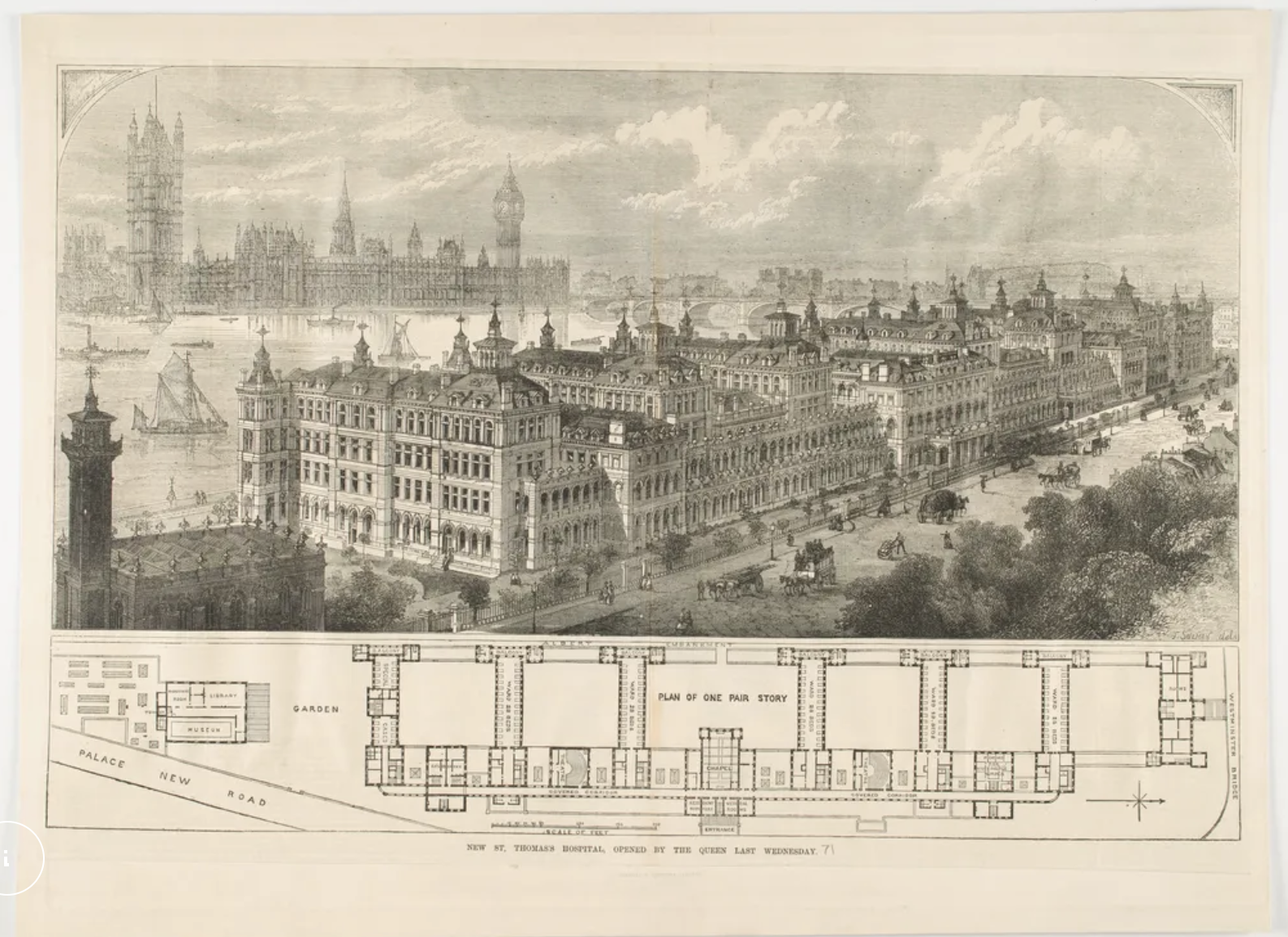

The London Museum website presents a picture of St Thomas’ hospital as an example of this architecture. There were seven such pavilions. As you see in the pictures below, the hospital rivalled the Houses of Parliament in its size and pinnacled magnificence.

This picture is from the London Museum website. The Tower I sketched is on the left.

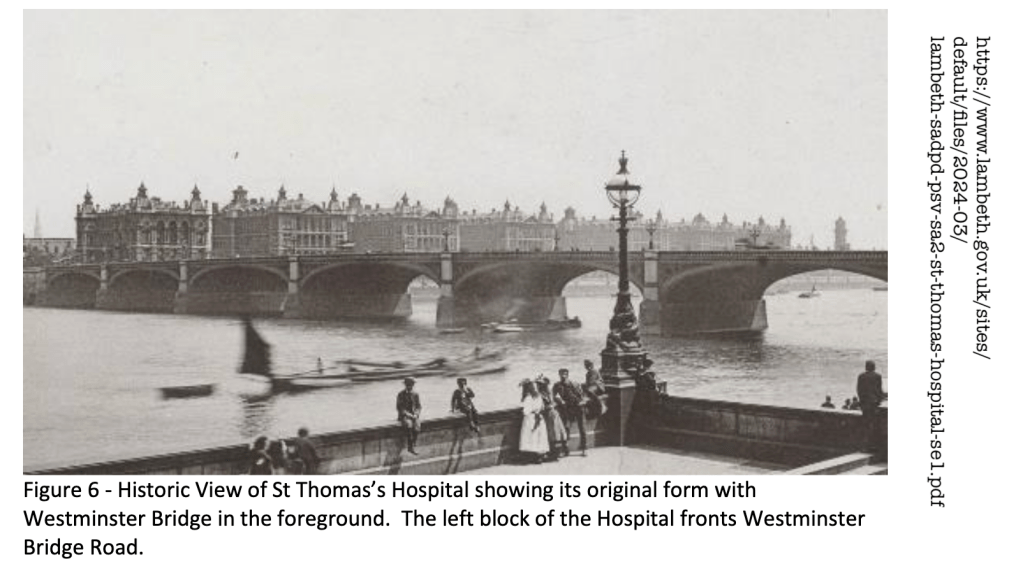

Here is a historic photo from the other side of the river. Westminster Bridge spans the river. The tower I sketched is on the right.

The hospital looks different today. The North pavilion was destroyed by enemy action in the 1939-45 conflict, and other parts of the building were damaged beyond repair. The only part remaining was the Tower to the south, and 3 of the southernmost pavilions. A large block was built in 1975 to replace the north pavilion. The website “Ebb and Flow” has some excellent pictures from 2023, showing the 1975 building in detail, and paying tribute to the dedicated people who work in this building.

Below is a photo from August last year. The 1975 buildings are on the left, the original buildings, still derelict, are on the right. In front is the National Covid Memorial Wall.

The remaining pavilions and the tower are Grade II listed, number 1080373. Many new buildings of the hospital have been created around them, including the Evelina hospital for children.

Now we can expect the renovation of the southern part of the hospital.

(https://micaarchitects.com/projects/st-thomas-hospital-block-9-prideaux-building)

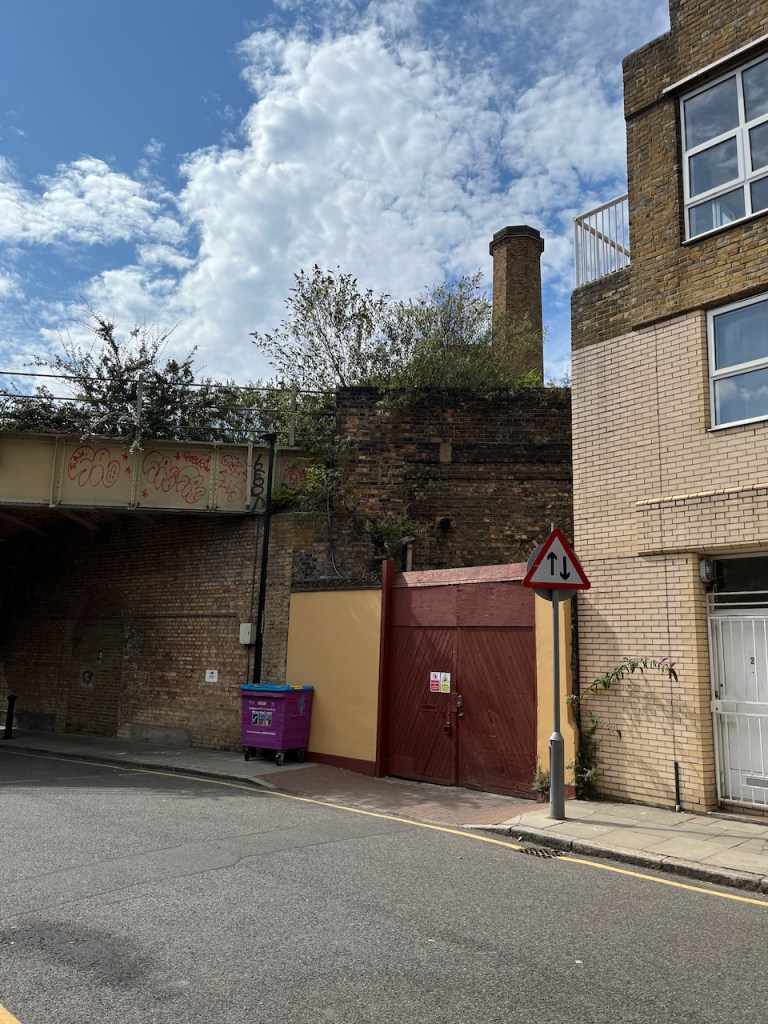

I have run and walked past this building for twenty years. I’m so glad that doing the sketch has prompted me to discover what’s going on behind the high walls. Here are some snapshots from the embankment. The hospital is on the right, behind the wall.

I thank the ambulance staff, administrators and medical professionals of St Thomas’ hospital who were there when needed after a terrifying incident.

We all have such incidents in our lives. The hospital is more than a building. It is a place of caring, a community and a store of knowledge, from Nightingale to now. Thank you NHS.

Note 1: The report from Mosaic civil engineers is called

“Mosaic Civil and Structural engineers report

FINAL REPORT

PHASE 1 PRELIMINARY CONTAMINATION RISK ASSESSMENT REPORT

01/07/2024″

It is on this link, as part of the ongoing planning proposal.

If that link doesn’t work, you can find it here: