— A tale of two tunnels —

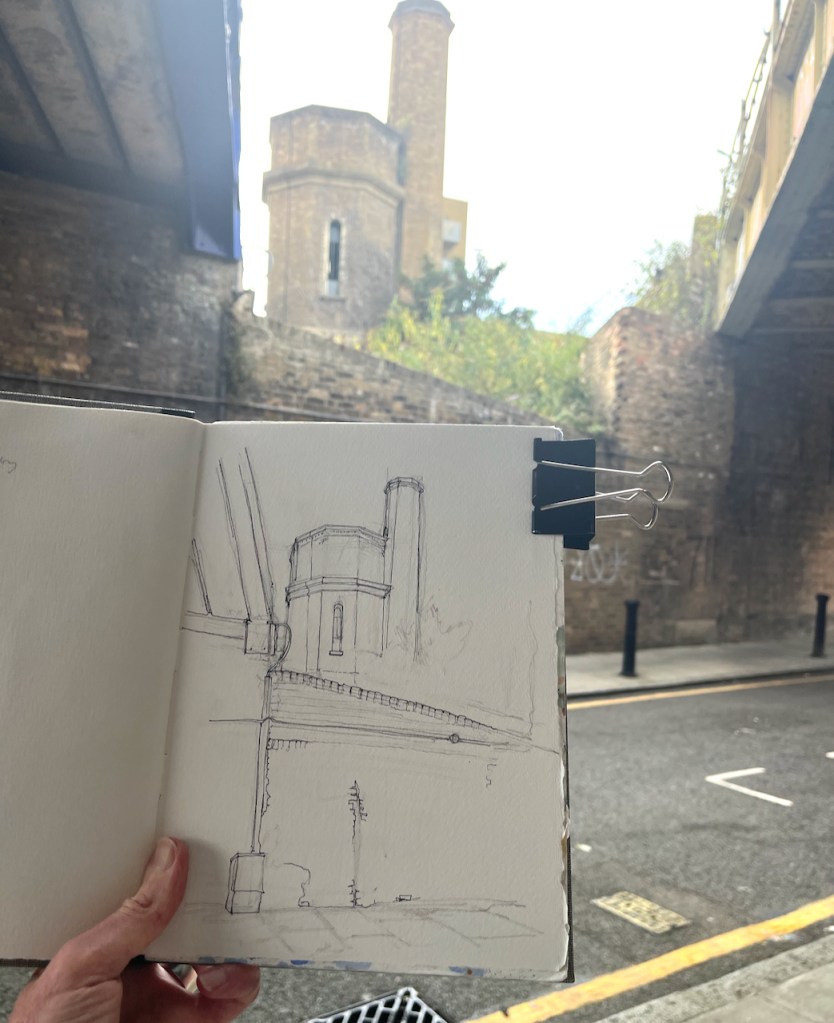

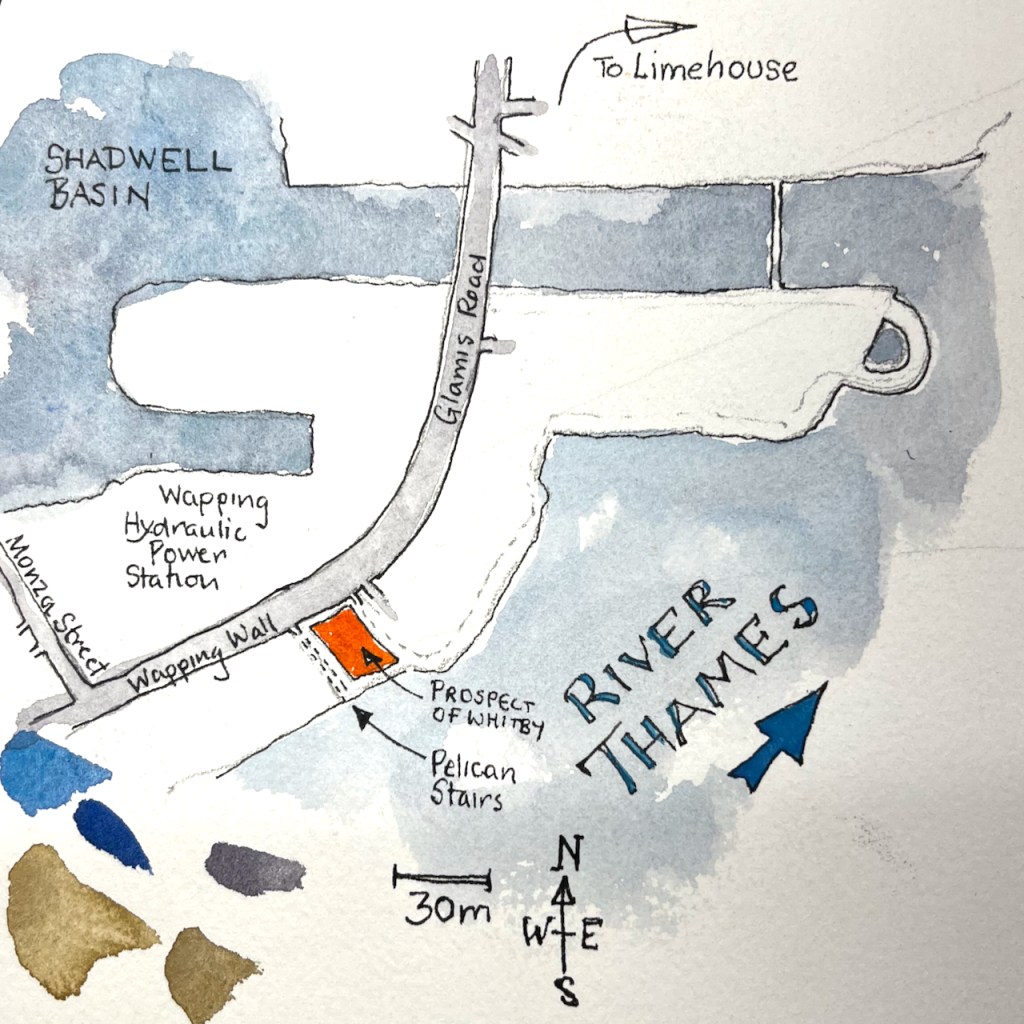

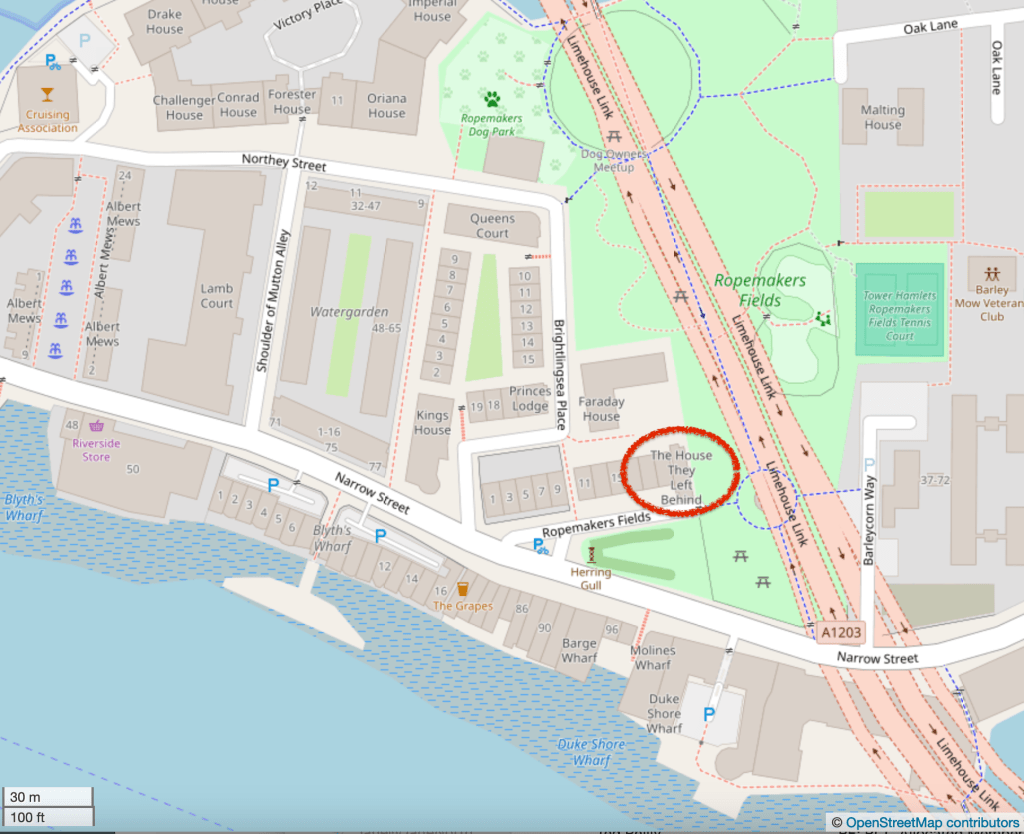

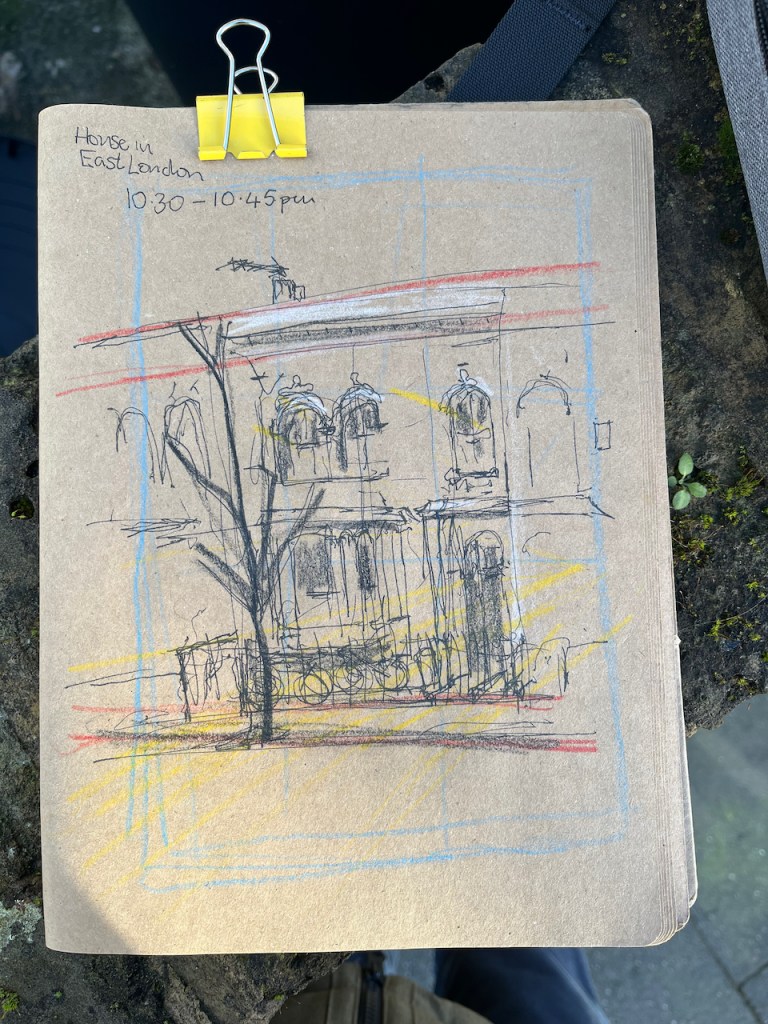

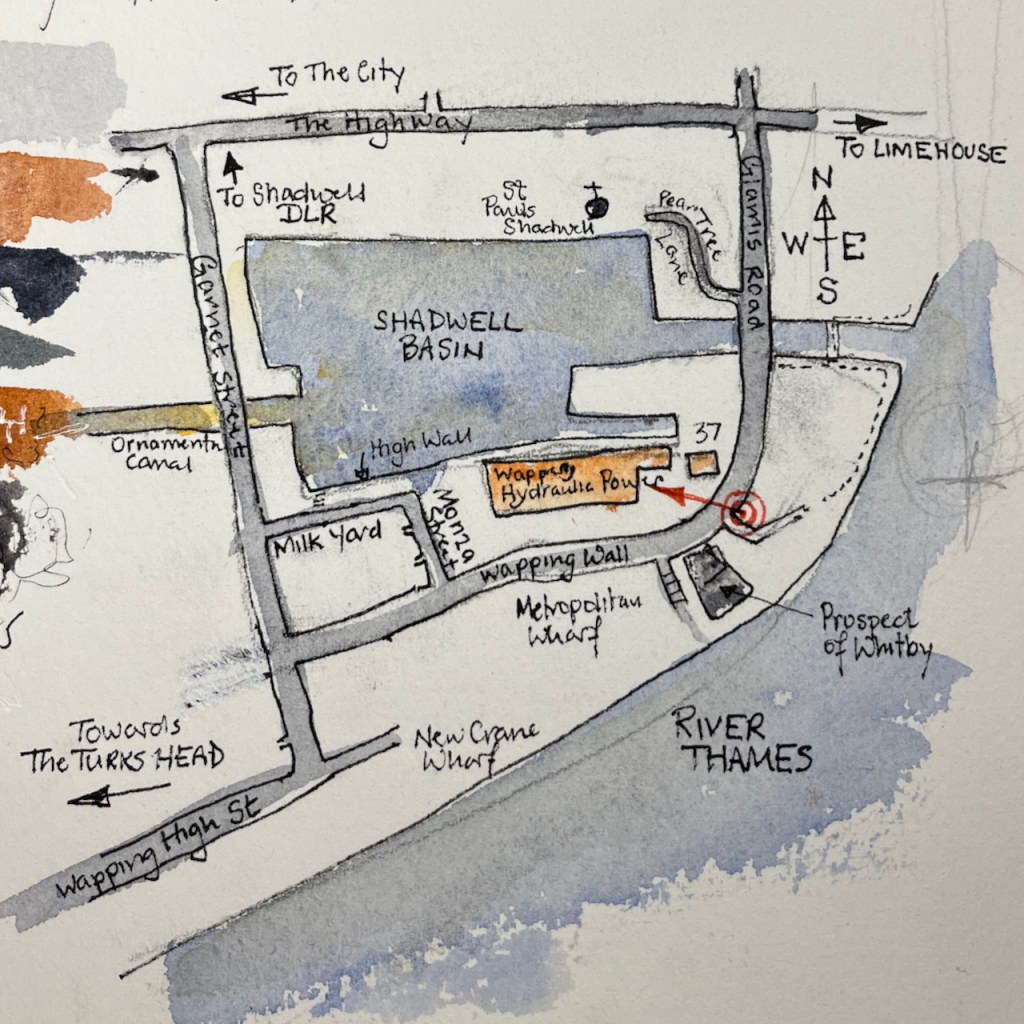

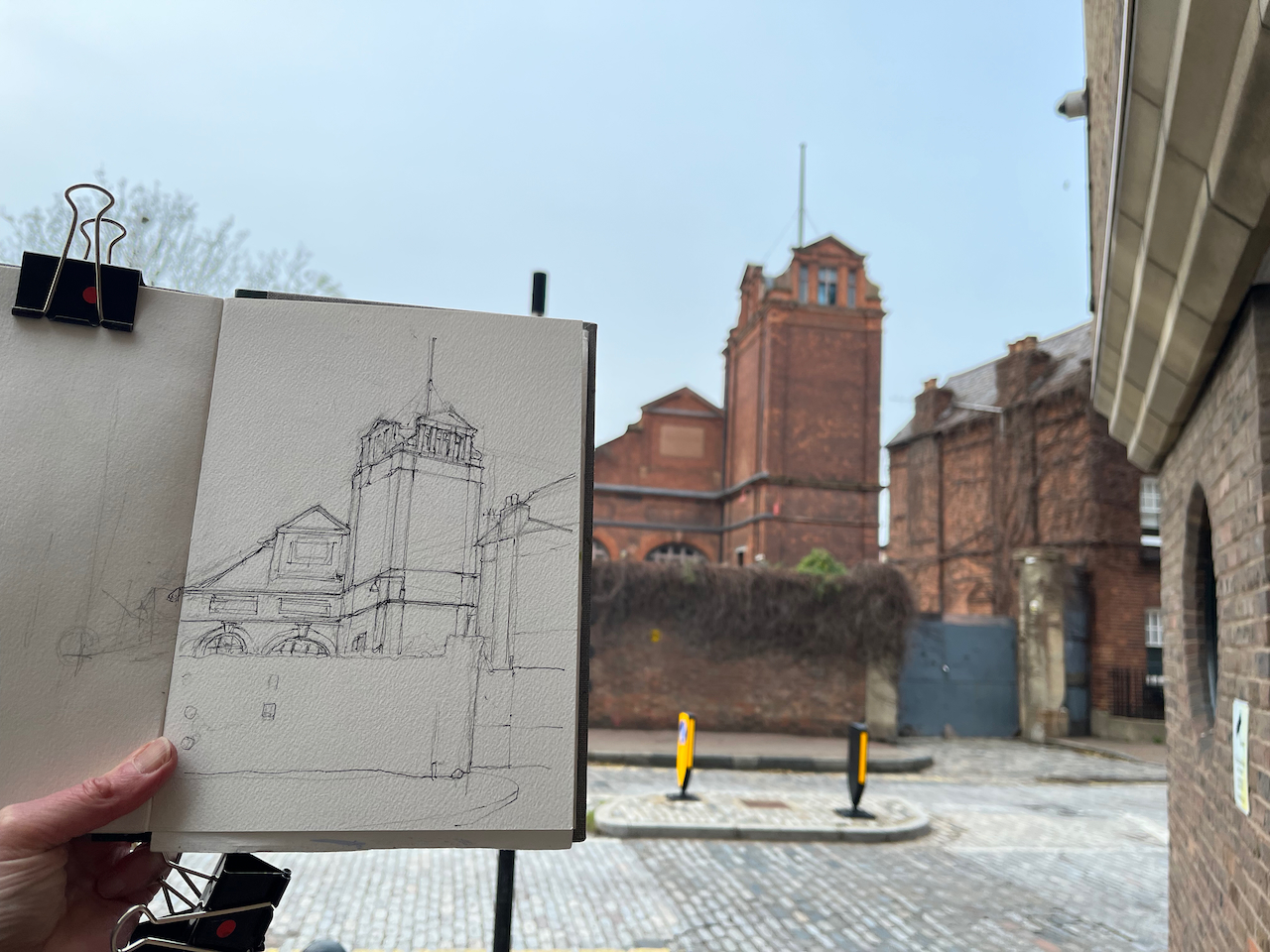

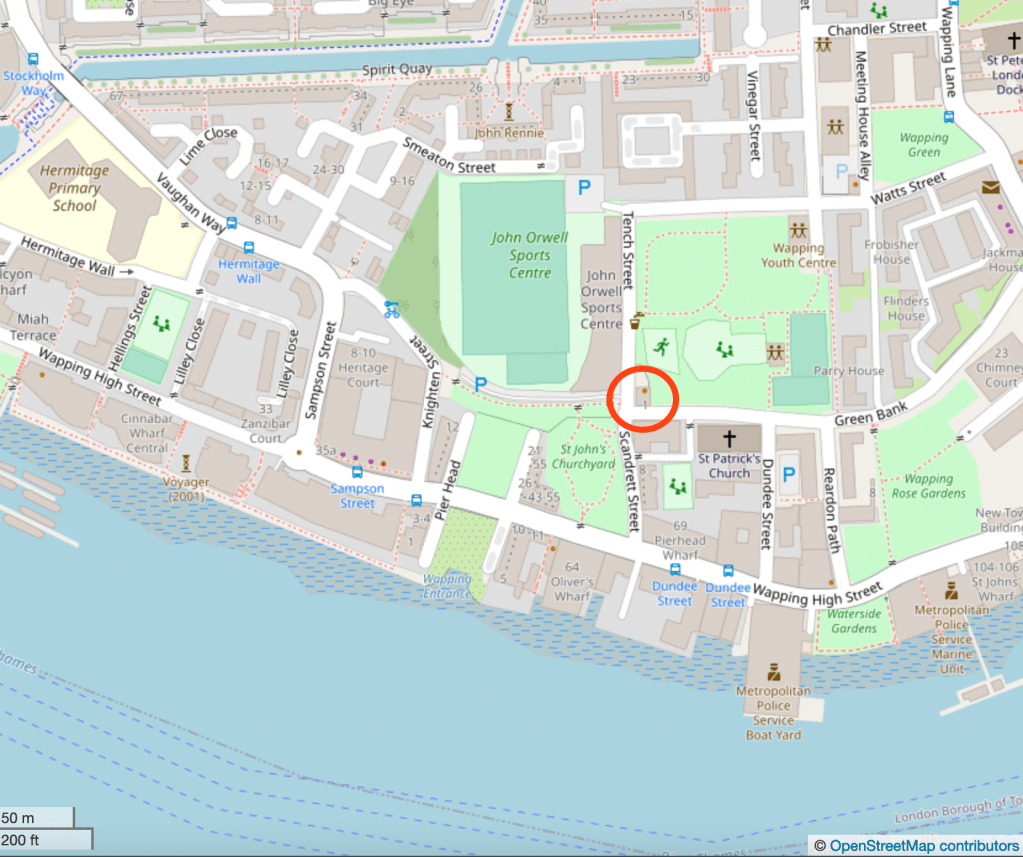

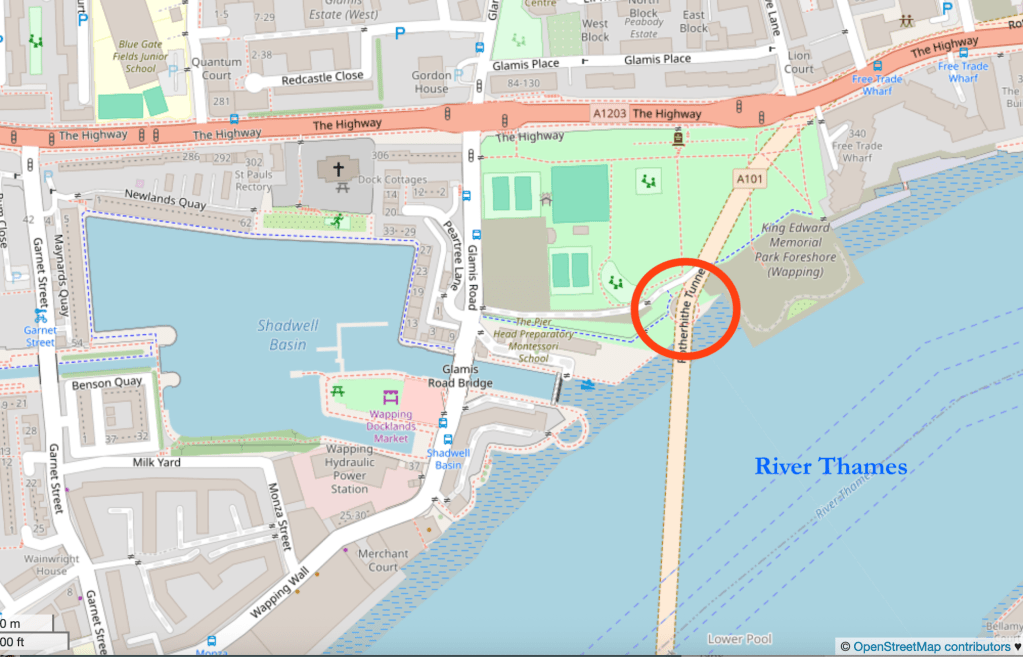

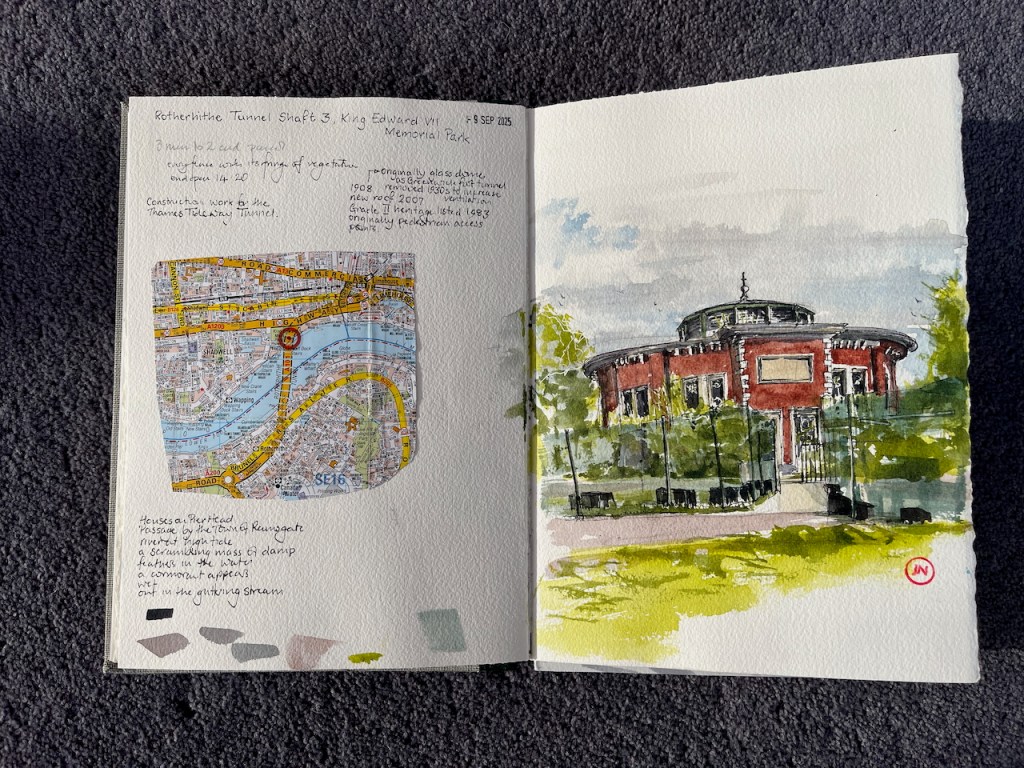

Construction work for the Thames Tideway tunnel surrounds this small round building on the north side of the Thames, near Shadwell.

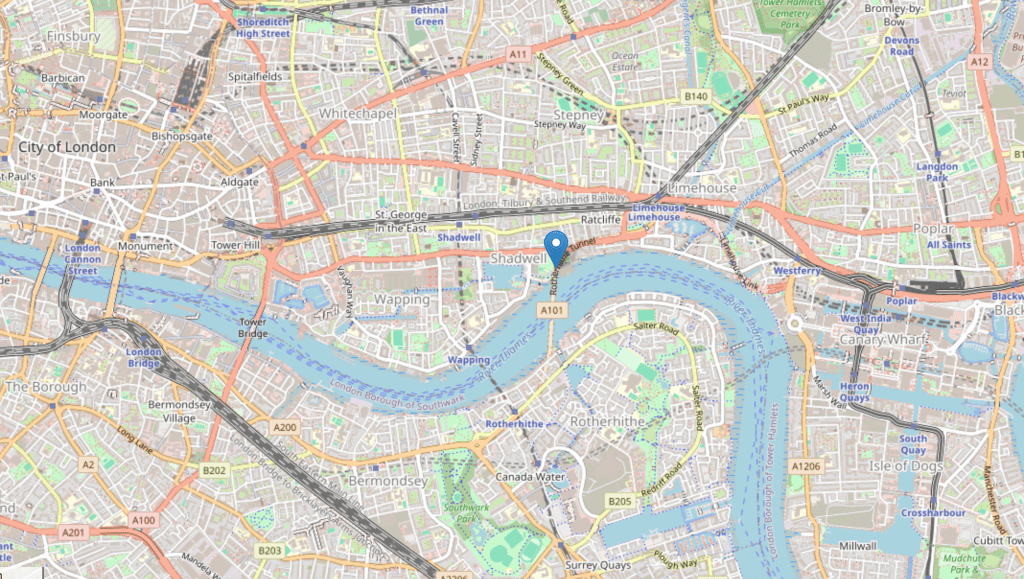

This building is an air shaft and access point access for the Rotherhithe tunnel. The Rotherhithe Tunnel carries road traffic between Rotherhithe on the south of the river and Limehouse on the north. It was constructed between 1904 and 1908, for horses and carts. The designer was Sir Maurice Fitzmaurice.

The tunnel links Limehouse on the north of the river to Rotherhithe on the south. Built originally for horse-drawn carriages and pedestrians, the tunnel now carries far more traffic than it was designed for, which requires careful day to day management by TfL to ensure safety.

Transport for London press release 20181

This circular building is one of four shafts giving access to the tunnel. It contains a spiral staircase, which was in use from when the tunnel was opened in 1908 until the 1970s2. This access is now closed to the public. The shaft building and the staircase are Grade II listed3.

The roof in my picture dates from a refurbishment in 20074. Originally there was a glass dome5.

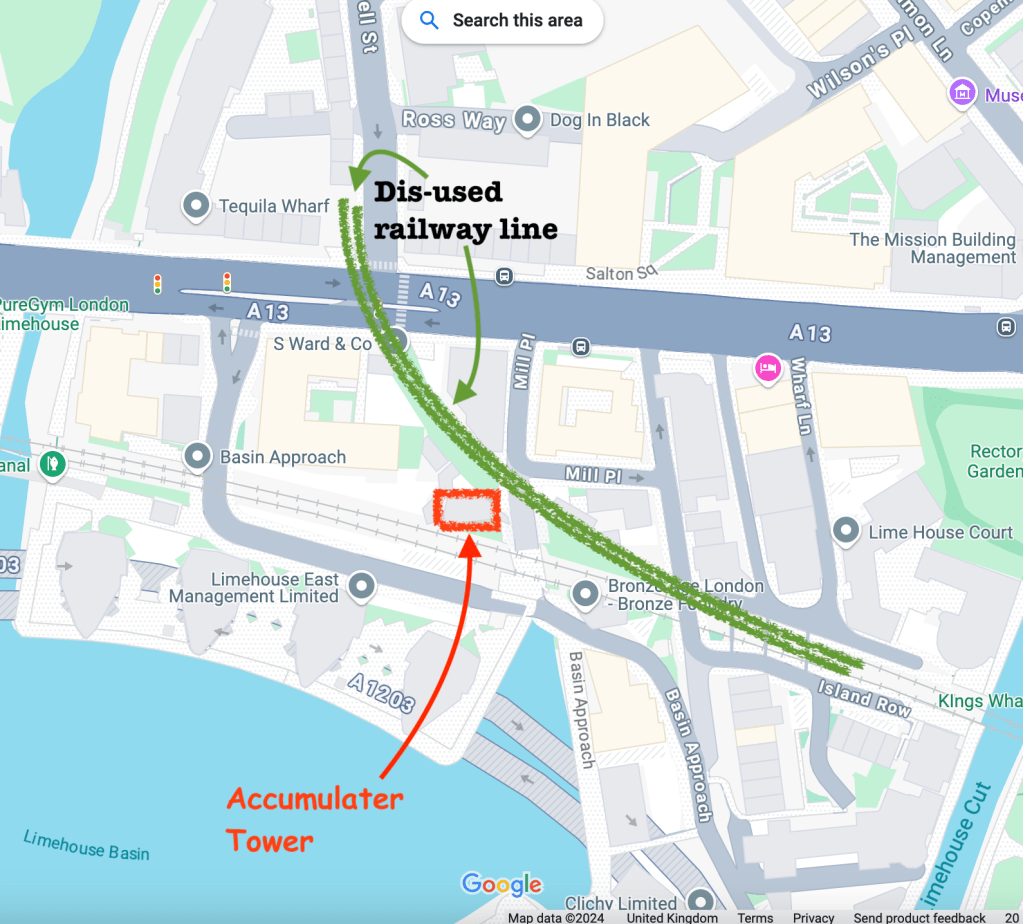

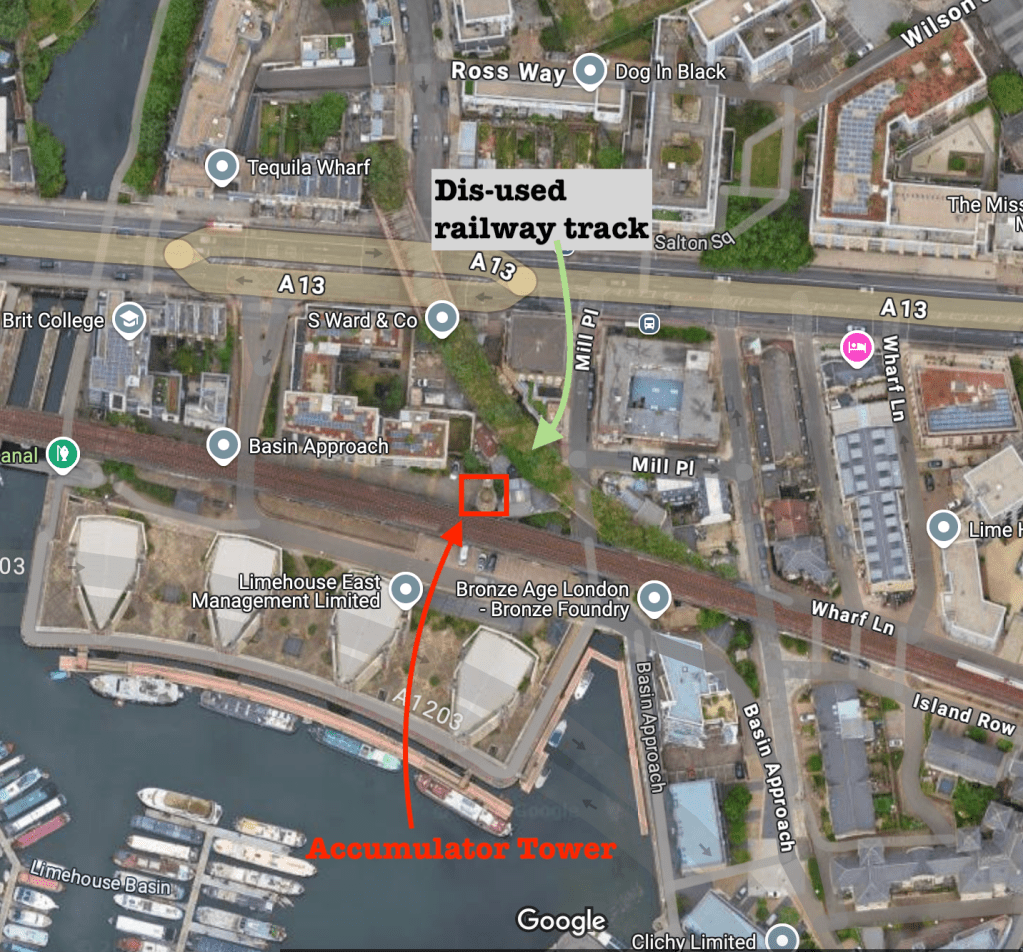

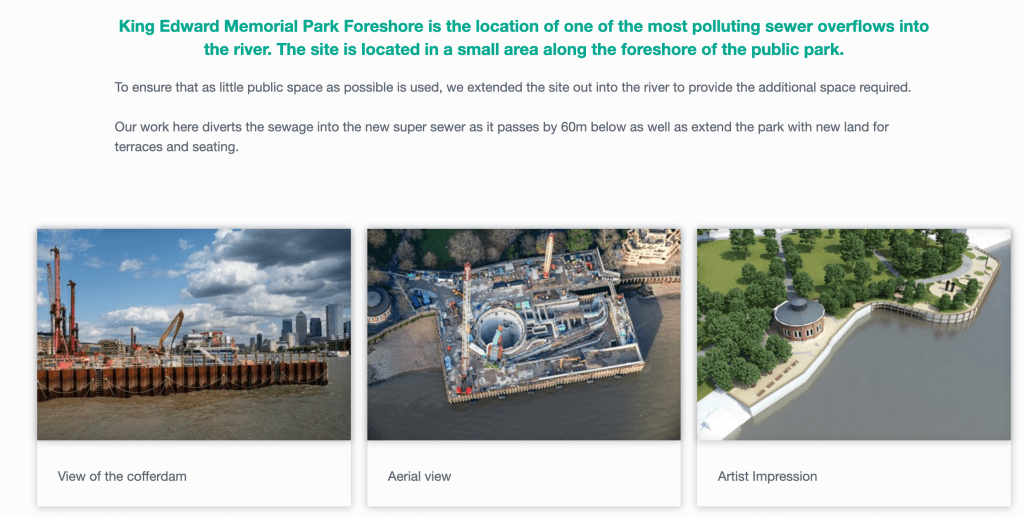

The fences in my drawing are the perimeter of a Thames Tideway tunnel construction site. The Thames Tideway Tunnel carries sewage from central London to Becton Sewage Treatment Works. It runs under the Thames. At various points there is a junction between this main sewer and a local sewerage system. The site at King Edward VII is one such junction.

The Thames Tideway tunnel runs longitudinally along the Thames, so it crosses the Rotherhithe tunnel, which goes across the Thames. But this is not a problem, as the Thames Tideway tunnel is 60m6 below the Thames and the Rotherhithe tunnel is just 23m down7. So they do not bump into each other.

I’ve read that you can walk through the Rotherhithe Tunnel starting from one of the the tunnel entrances and passing under the shaft I’ve drawn. Those who have tried it8, even during the pandemic, do not recommend the experience. The tunnel is highly polluted from the vehicle fumes, and the pavement is narrow. It’s even pretty terrifying to drive through it in a car. Close the windows and the air vents, and stay alert while driving. If you’d like to walk a Thames tunnel, I recommend the Greenwich Foot Tunnel, or the Woolwich Foot tunnel, both of which I’ve walked. They are fun, eerie and have no traffic to pollute the air. You can read about my excursion to the Woolwich Foot Tunnel here.

Disambiguation: The Rotherhithe Tunnel I’m talking about in this post is not the same as an earlier tunnel built between 1825 and 1843 by Marc Brunel, and his son, Isambard. This Brunel tunnel was a little further upstream, and is now used as a railway tunnel only.

References:

- Transport For London Press release 12 June 2018 contains data about the numer of vehicles using the tunnel: https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2018/june/rotherhithe-tunnel-celebrates-110-years-of-transporting-people-across-the-thames ↩︎

- Access to the tunnel via the shafts was from 1908 until the 1970s. FOI FOI-0398-2526 confirms the presence of stairs inside the shaft building: TfL Freedom of information request FOI-0398-2526: https://tfl.gov.uk/corporate/transparency/freedom-of-information/foi-request-detail?referenceId=FOI-0398-2526 ↩︎

- Historic England Listing: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1260101?section=official-list-entry ↩︎

- Roof replacement 2007 confirmed by King Edward VII park “Management Plan” 2008 page 15: “The park surrounds the tunnel vent and access shaft to the Rotherhithe Tunnel. The tunnel was opened in 1908, the vent was present before the park was constructed, and early images of the park show that it visually dominated the site. The tunnel vent remains an important feature, but is no longer so visually dominant due to the present day maturity of trees in the park. The Rotherhithe Tunnel was refurbished in 2007 and a replacement roof was installed as part of these works.”

Link: https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/Documents/Leisure-and-culture/Parks-and-open-spaces/king-edward-management-plan.pdf ↩︎ - Roof of the shaft:

1908 – glass dome,

by 1946 – no roof (removed in the 1930s),

from 2007 – current roof as in my drawing.

Evidence:

London Picture Archive has a picture of the shaft in 1921, where you can see the glass dome that covered the shaft. Record number 118817, Catalogue number SC_PHL_01_392_A360 See this link: https://www.londonpicturearchive.org.uk/view-item?WINID=1762114518393&i=121045. They also have photographs from 1971 where it’s clear that the roof has been removed completely. See photo on this link, record number 237845, catalogue number SC_PHL_02_0666_71_35_217_30A: https://www.londonpicturearchive.org.uk/view-item?i=239938

“A London Inheritance” post contains an aerial picture from 1946 showing that the roof had been removed by that date. See this link. This post says: ” The following photo dated 1946 from Britain from Above shows the park at lower left. Note the round access shaft to the Rotherhithe tunnel. In the photo the shaft has no roof. The original glass roof was removed in the 1930s to improve ventilation. The current roof was installed in 2007.” ↩︎ - Thames Tideway Tunnel information from the Tideway tunnel website: https://www.tideway.london/locations/king-edward-memorial-park-foreshore/ ↩︎

- Depth of the Rotherhithe Tunnel is from the website of the Rotherhithe & Bermondsey Local History Society on this link: https://www.rbhistory.org.uk/rotherhithe-road-tunnel ↩︎

- Walking through the Rotherhithe tunnel: see for example “Ian Visits” : https://www.ianvisits.co.uk/articles/walking-through-a-tunnel-under-the-thames-part-1-11764/ ↩︎